Dear Readers,

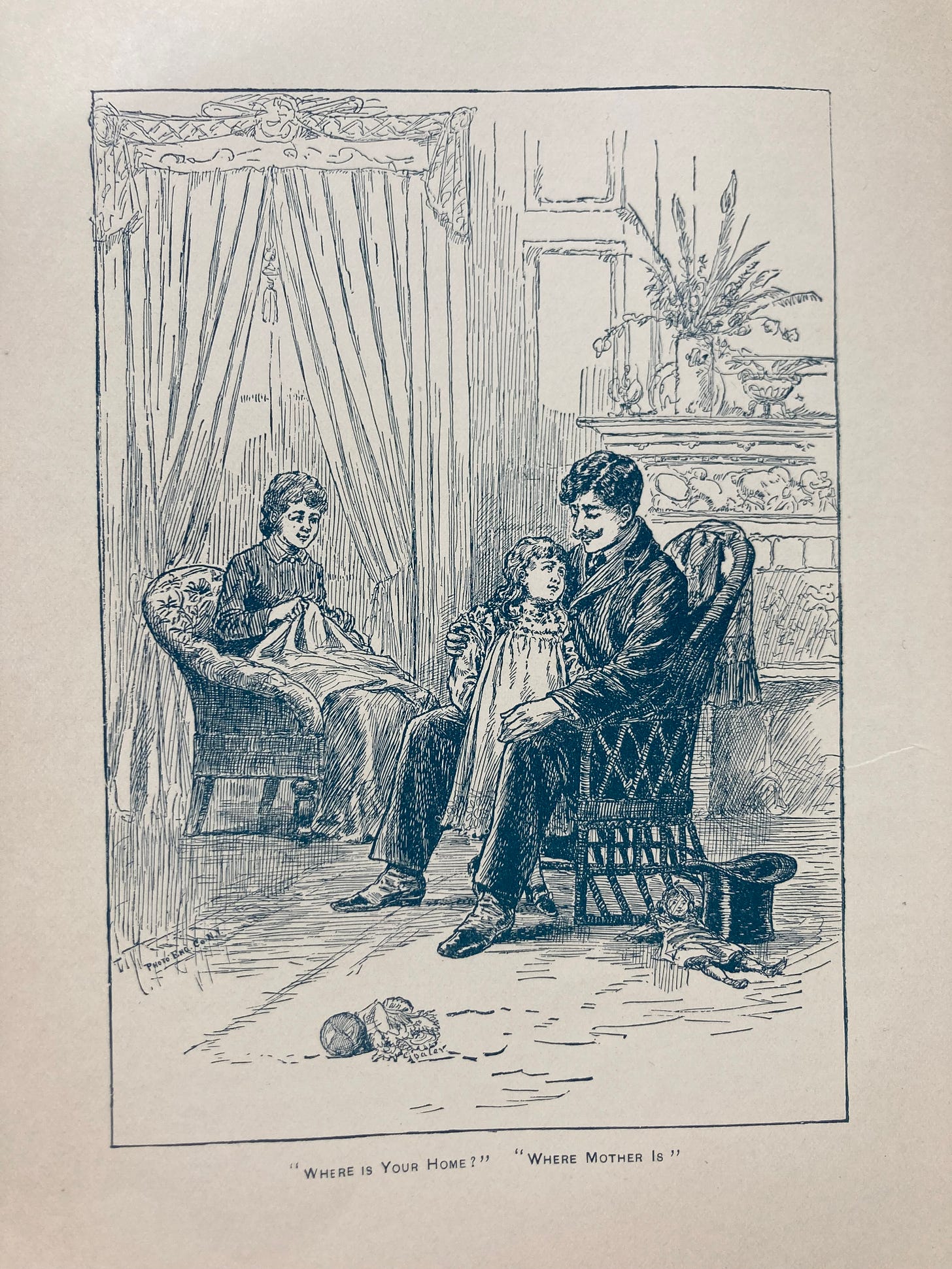

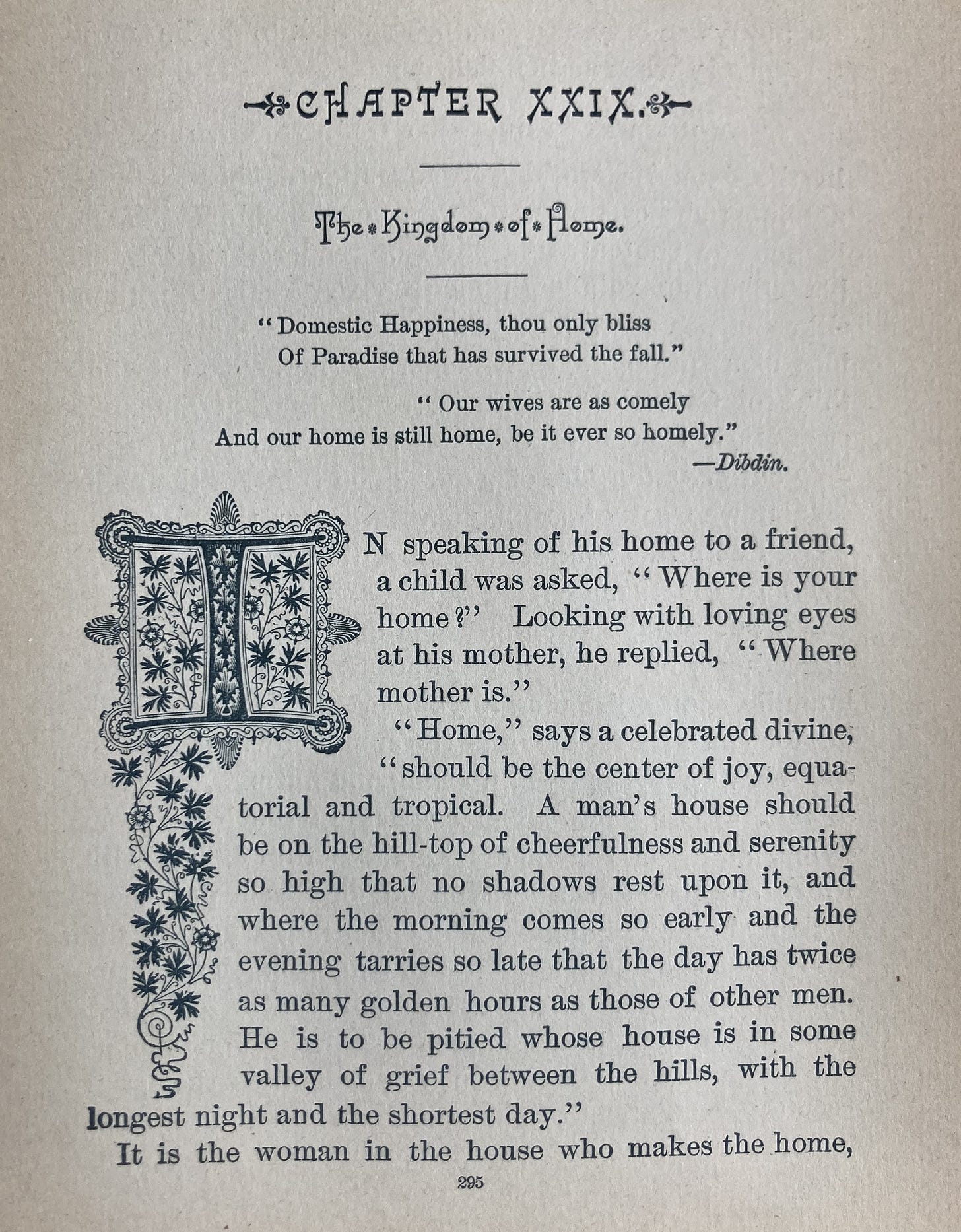

The Kingdom of Home is the last chapter about work in What Can a Woman Do?, the 1893 book I wrote about last week. It is too good a title to let slip from this summer’s thoughts about the women who baked me and what influenced their formative years, which were, coincidentally, the formative years of factory bread.

The Kingdom of Home referred to the late 19th century battle between the cult of domesticity and its opposing social concept, the New Woman, but the phrase fits the internal dialogues and external pressures I’ve felt as an adult. I resisted domesticity and motherhood as a young writer, and I’ve wrestled with who I am as a mother, worker and person for the 27 years I’ve straddled these identities. If Mrs. M.L. Rayne, author of What Can a Woman Do? believed — after 300 pages of career advice — that the ultimate calling for women was to keep house and raise children, no wonder these ideas still reverberate!

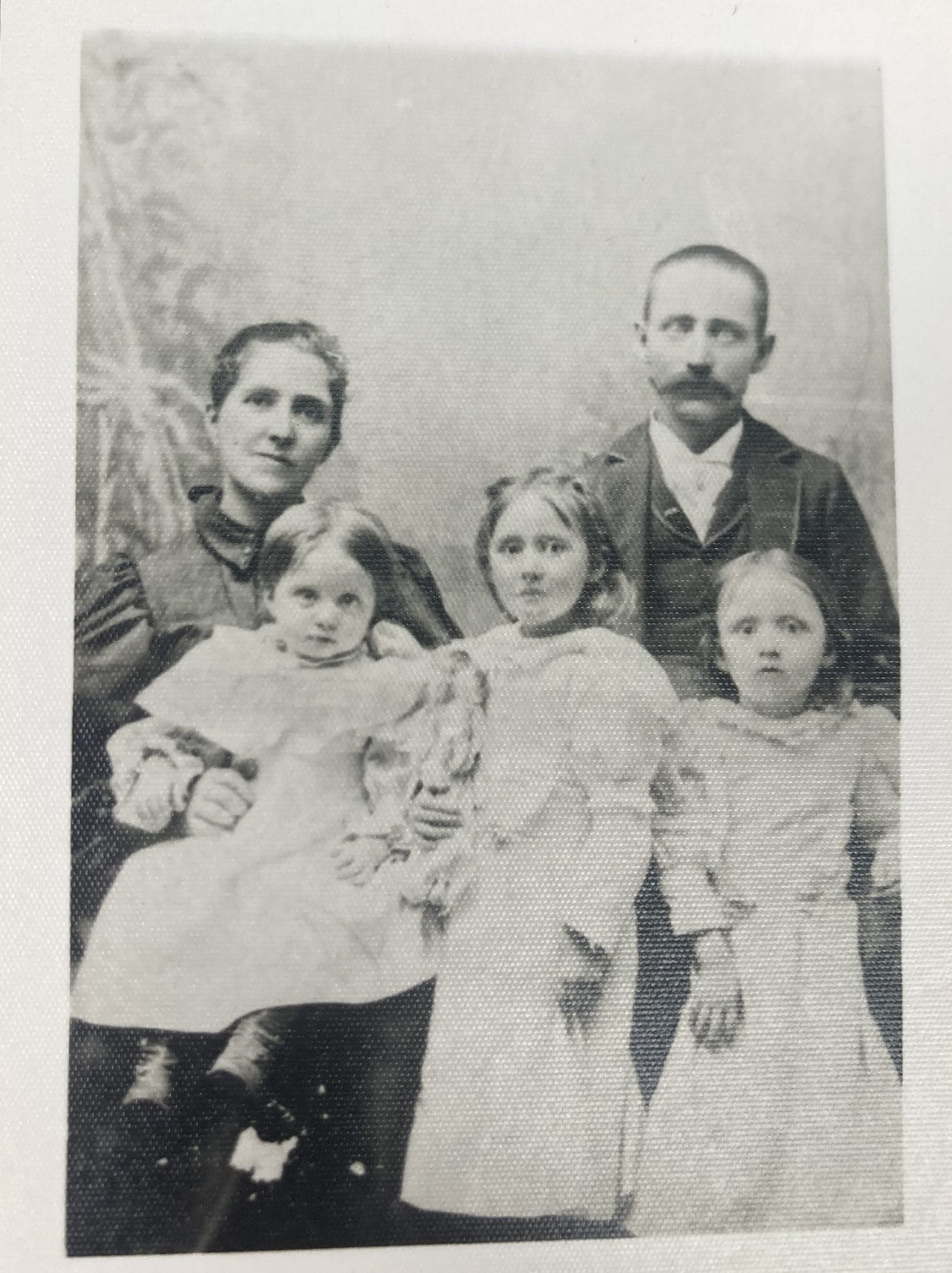

I’ve been wondering how these dueling ideas affected my great-grandmothers as they raised their daughters. Pictures of the Cole family show traditional Victorian dress, lacy collars and high-button shoes. I think my Halloran and Sweeney forebears dressed similarly, but I’m pretty sure that questions over women’s dress and lives didn’t register to my Zaleska relatives, who were still in Poland. This picture of the Greenaway family from 1895 — I’m not related to them but feel a kinship with Minnie, who became a writer — looks of its time, too. How did these mothers feel about who they were, and who their daughters would be? Did they ride bicycles? Were they itching to get out of their corsets?

I don’t have any diaries, so I looked at public records, in local newspapers from 1895-1915. I searched for searched for the words “new woman” and most of the results were derogatory. I was not surprised by the negativity, but by the variety of ways that changing roles for women were trashed. A piece on higher education lamented that once women outnumber men as doctors, lawyers, architects, and steamboat captains, “What are the men going to do then? Where will they be able to find a living? Who is going to buy the ice cream and the oyster suppers and the theatre tickets then? Who will rock the cradle?”

Another jab was placed on the Society and Woman page, under an iconic image of a Gibson Girl. She stands elegantly and significantly, asserting the proper attire and accompanying social role for women, above a column reprinted from the New York Sun. “A Study of The New Woman” cuts at its subject not in moralizing prose, but through a back-and-forth dialogue between one universal and anonymous man and another. The extensive volley begins as follows.

Do you see it? What? That. That what. That living organism over there on the street corner. That’s a new woman. What’s a new woman; one that isn’t old? Oh, no, one that new in the sense of novel. What's novel about her? Several things but underlying them all are ideas. Has she ideas? That’s what she prides herself on. Is it so unusual for a woman to have ideas? She thinks so. So what kind of ideas has she? New woman ideas, mostly. What kind are they? Heterogeneous and scattering. What does that mean? Um-er-well, no two alike and all headed different ways. Hasn't she an object? She is one. But she must have some definite aim? Just about the same kind of an aim a natural woman has when she throws a stone at anything. You say natural woman, isn’t the new woman natural? She was born that way but she tries to outgrow it. Why? That’s one of her ideas. Has she any more like it? Not like it, but of the same class. What does she do with them? Exhibits them, principally. To whom? Oh, it’s a free show. That means she is promiscuous to her audiences? Pretty much promiscuous. Would she soon have women as men? Not quite. That is to say, she wants to convince the women and convict the men. Convince the women of what? That they are a down-trodden sex? Do the women believe her? And convict the men of what? That they are down-treaders.

Here’s another striking exchange from the piece:

She argues for dress reform; she advocates a mild form of Independence; she suggests a wider intelligence for the good of woman regardless of man. Does she win many converts? She wins some, and sets a good many to thinking. Why isn’t she successful with all women? She is too radical. The average woman, after 6000 years of being a woman, woman finds some difficulty in growing whiskers and putting on pants in a hurry.

Dress reform is code for social reform. Change women’s garments and shatter the delicate balance of civilization. My great-grandmothers, and Rose Maud Murray, Minnie’s mother, read articles like these, and I wonder how these words struck them.

I am guessing that Catherine Lewis Cole, born in Ireland, was glad for traditions. Hers were Catholic, and two of her daughters, Helen and Mary became nuns. Juliette worked in collar factories1 before she married, and Georgiana worked as a secretary before she did. Their sister Jane stayed home and took care of her parents. Charlie did not, as was often the case in Irish Catholic families go to seminary. Perhaps he was spared because he was the only boy?

Of all the Cohoes women who baked me, only Minnie Greenaway went to college. She graduated in 1926 from the New York State College for Teachers, with a B.S. in Commerce, for teaching business skills in high schools. I can’t know if her parents pushed her, or whether her drive was internal. Higher ed for women was unusual. My great aunts became nuns not just to serve God, but because it was a viable path to education and a job. In 1920, only 7% of women earned a bachelor's degree, and the number only notched up to 10% by the end of the decade.2 The most affordable form of higher ed were state teacher’s colleges. In NYS they were free.

Teaching was an acceptable and even noble profession for women. “A teacher is fitted to appear in the best society, as the result of association with the cultured and refined educators of youth,” wrote Mrs. Rayne. The young, unmarried women who taught in Cohoes likely attended the Normal School/NYS College for Teachers in Albany.3

Miss Vischer, Miss Hayward, and Miss Nichols taught Minnie and her sisters, and my grandmother and her siblings at Cohoes School #5.4 The teachers likely reinforced standard boy/girl patterns in their lessons. The project of shaping girls into mothers and boys into men did not begin with them.

I wonder what they thought of the New Woman. Did they only see her in newspaper articles, and have mixed feelings about the admonishments levied against anyone breaking tradition? Or were they happy to repeat standards, and not challenge them?

I wonder when their girl students encountered social expectations of gender. Minnie got the memo early; her memoir begins with the fact that her father wished she was born a boy so he could pass on the family profession of baking. I wonder how my grandmother and great aunts felt about being girls and women. Maybe the limits and differences dawned on them gradually, as they figured out that only certain doors were theirs to open. Or perhaps they always accepted that gender was a two-lane road.

Their penmanship and reading lessons were filled with morals. The Spencerian method taught cursive through copying lines like Constant occupation prevents temptation, Good examples are convincing preachers, or Indolence is a grave for the living man.

What about bread morals? Ideals that baking bread was a mother’s duty and love were still strong. In 1911, when Minnie was 12 and my grandmother was 9, the National Master Bakers Association published The Story of the Staff of Life, a handout promoting bakers’ bread, and condemning the quality of homemade bread. Yet I doubt my great-grandmothers baked bread at home. In the 1890s and early 1900s, ovens were wood or coal fired, and finicky to use. Even though bakeries were small scale in Cohoes, it was likely cheaper and easier to buy bread than bake it. In Minnie’s family, her father was a professional baker, so their bread definitely was not homemade. My grandmother, my father said, only ever liked to cook one thing: the war surplus cake he loved. Her mother was from Ireland, where quick breads, not yeasted loaves were the norm.

1911 was the year that a Philadelphia baking family, the Freihofer’s came to Troy, on their way to Montreal to see a traveling oven, which ran pans of dough through an oven on conveyor belts. They saw our City of Women, loads of women workers flooding to the many detachable collar and cuff factories. One in three women in Troy worked in this trade, and the Freihofer’s saw a market. Two years later, the Freihofer’s bakery opened at the north end of my city, like a brick bookmark.

I’ll leave you with a picture I found at my sister Elissa’s store. The woman has a bun, and her hands are blurry with work. I am guessing she’s scrubbing laundry, but the pan looks like it has food. A barefoot girl stands next to her, arms behind her head, looking at the photographer. The mother has a furrowed brow and frowns, her eyes on her work.

Whatever ideas circulated about how women should be, here is a snapshot of what one woman, and likely many women did. I keep it on my desk to remind myself of a reality of life in the era that intrigues me.

Yours, Amy

Troy was the Collar City because 90% of America’s detachable collars and cuffs were made here, some of them by my relatives.

Normal schools took their strange name from the fact that they are teaching colleges, established to teach the norms of education.

My grandmother used these names in a letter she wrote Minnie after the publication of her book All Wool But the Buttons: Memories of Family Life in Upstate New York.