Dear Readers,

When I was young, I am told I bellowed:

My permission for going swimming!

I’m not sure whether I misunderstood how to ask or was asserting my desire. Either way, the phrase came to define me as someone who declared ideas. When I got to college in the fall of 1984, though, I met attitudes that confused and quieted me. A chatty straight-A from a small town, I wasn’t used to being dismissed because I was female. I wished that I could be valued for my thoughts, like the males around me, and my internal patter shifted: My permission to be a person!

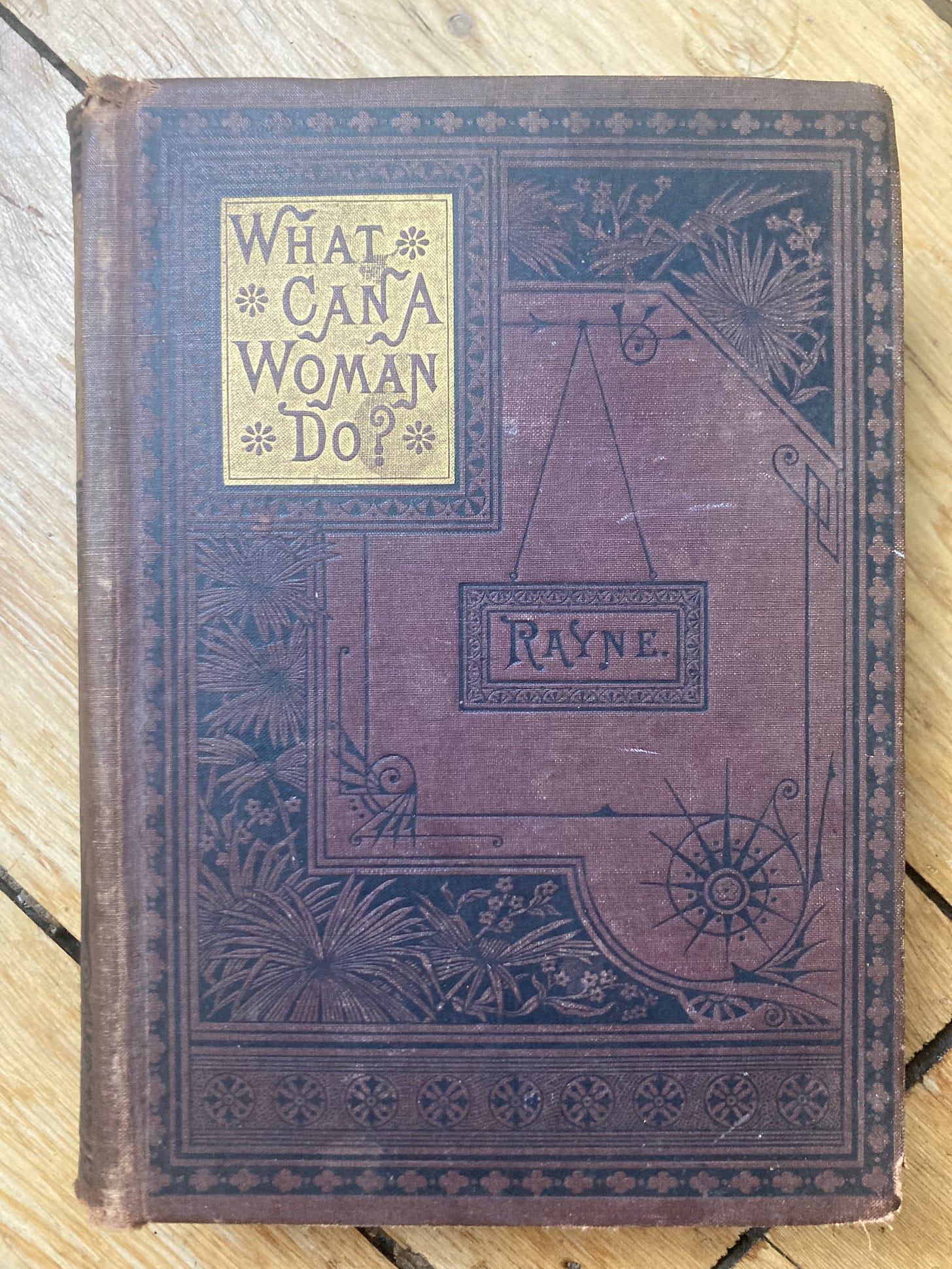

I still wrestle with social concepts of gender, and marvel at what pressures the women who baked me – Minnie, my grandmothers, great aunt Juliette – faced. Trying to understand their choices, I’ve turned to What Can a Woman Do?: Or Her Position in the Business and Literary Worlds, an 1884 book written by Mrs. M. L. Rayne. The Graphic Arts Collection at Princeton posted a nice writeup of the book, and variations that the catchy name inspired. I was given a copy in my late teens but only started reading it this summer.

In the preface, Rayne sets the stage for just how revolutionary the book would be:

“The day has gone by when a woman who enters any pursuit of industry loses caste. It is not necessary that she lose that essential charm of womanhood, which is her natural heritage, because she turns the pages of a ledger. The whole tendency of her being is to grow in womanly strength, not to develop into some kind of a masculine nondescript.”

Employment in the Victorian but modernizing world threatened lines of gender, but fear not, Rayne assured, professional women would remain women!

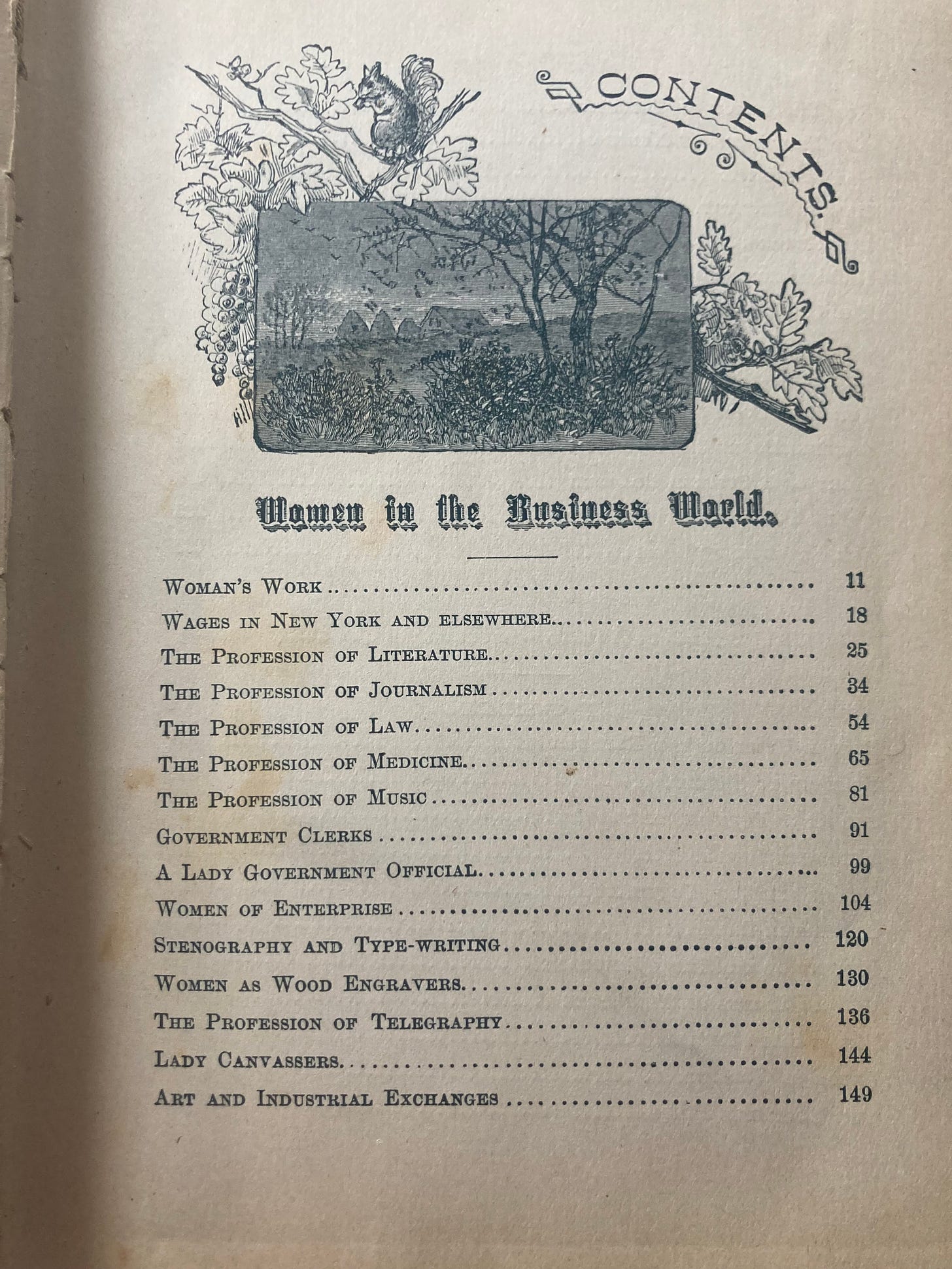

Women could be A Lady Government Official or Women of Enterprise, aka, an entrepreneur. Rayne gives examples of women’s innovations, including a claim that an unnamed woman invented the improvement to horseshoe machinery that made my city of Troy a serious producer. (I have yet to find any evidence.)

Stenography and typewriting, wood engraving, selling homemade goods at an industrial exchange are other options on the smorgasbord. She clearly states how little women will earn compared to men, describes the work, and gives specific advice. Here’s what she said to would-be journalists:

“Use concise terms; have a choice of words; be anything but commonplace. If you attempt to describe a horserace, put motion into the article; make it so picturesque and full of life that your readers can see the flying animal, the crowd of spectators, and hear the loud cheers that announce the winning heat. Give strength and beauty to the simplest things you describe; use a lead pencil and eraser, and strike out any sentence that is not a picture.”1

On elocution:

“Speech is the temple in which the soul is enshrined. Why should we not be proud to keep such a temple in repair?”

On stenography:

“Shorthand writing is a very artistic work, and is well suited to the finer nature and more delicate organization of womankind. No profession affords a better opening for young ladies who desire to earn their own living than does shorthand and typewriting, and we know of no more agreeable and profitable employment in which they can be engaged. The prejudice against employing young ladies in office-work is rapidly dying out.”

On doctors:

“To be a successful physician a woman must be a lady — a womanly woman. No aping of masculine habits, dress or foibles will conduce to success. She must have an affinity for the work, feel at home in the sick room, with a desire and tact to relieve suffering, devoid of any morbid sensibility at sight of pain, offensive deformities and ghastly injuries and operations; she must be born to command, firm in purpose, and quick to execute.”

On nurses:

“She was calm, patient, and sympathizing; but, though eager to please and cheer the invalid, she did not stoop to simulate an affection she did not feel, nor to express hopes of recovery that could not be realized.”2

Rayne warned (paid) working women to also seek rest:

“A woman goes home to encumber herself with petty cares — sew a dress waist together, mend old garments, baste ruffles into a costume for the morrow, or take up some new form of work and worry. She is not satisfied with doing a man's work all day, but she will employ herself with a woman's work all the evening, vainly imagining that she finds rest in a change of labor. It is all a mistake. She wants a brisk walk in the open air— a pleasant chat with lively company— something that will divert her mind from work and weariness, as a ride or a stroll does her stronger brother; but she cannot sew, knit, or embroider, or do other work until a late hour every night, when she has worked nine hours of the day; she will break down in health, and the fault will be laid ignorantly at the door of her trade or profession.”

Initially I thought the book was written for the New Woman, which refers to a wave of gender nonconformity that began in the late 1800s and stretched nearly to 1920. The New Woman worked outside of the home (until she married), fought for suffrage, and generally ruffled social feathers – sometimes even wearing bicycle-friendly garments and riding bicycles! However, while Rayne champions a world of possibilities, Lady dentists! Female sales clerks! – she clearly has her heart in another camp – the cult of domesticity.

The cult of domesticity started in the 1830s and 40s, and I’ve understood this phenomenon as a response to industrialization. As work left subsistence homesteads, tasks became more gendered, and women’s jobs remained at home, and outside of the marketplace. The social need to make white women of the growing middle class satisfied with narrowed, indoor lives gave rise to writers and speakers valorizing female labors. Bread baking was a big part of this idealism, and writers of domestic advice manuals preached a gospel of home baked loaves — Rayne preaches this too. Fear not — I’ll get to it.3

However, now I see the cult of domesticity as a political effort, too. This is thanks to another book, Americanon: An Unexpected U.S. History in Thirteen Bestselling Books. Jess McHugh frames this categorization of (again, white, middle-class) women’s work as part of nation-building in the new republic. Keeping home and raising children was an important industry, and the family was a factory of citizens.

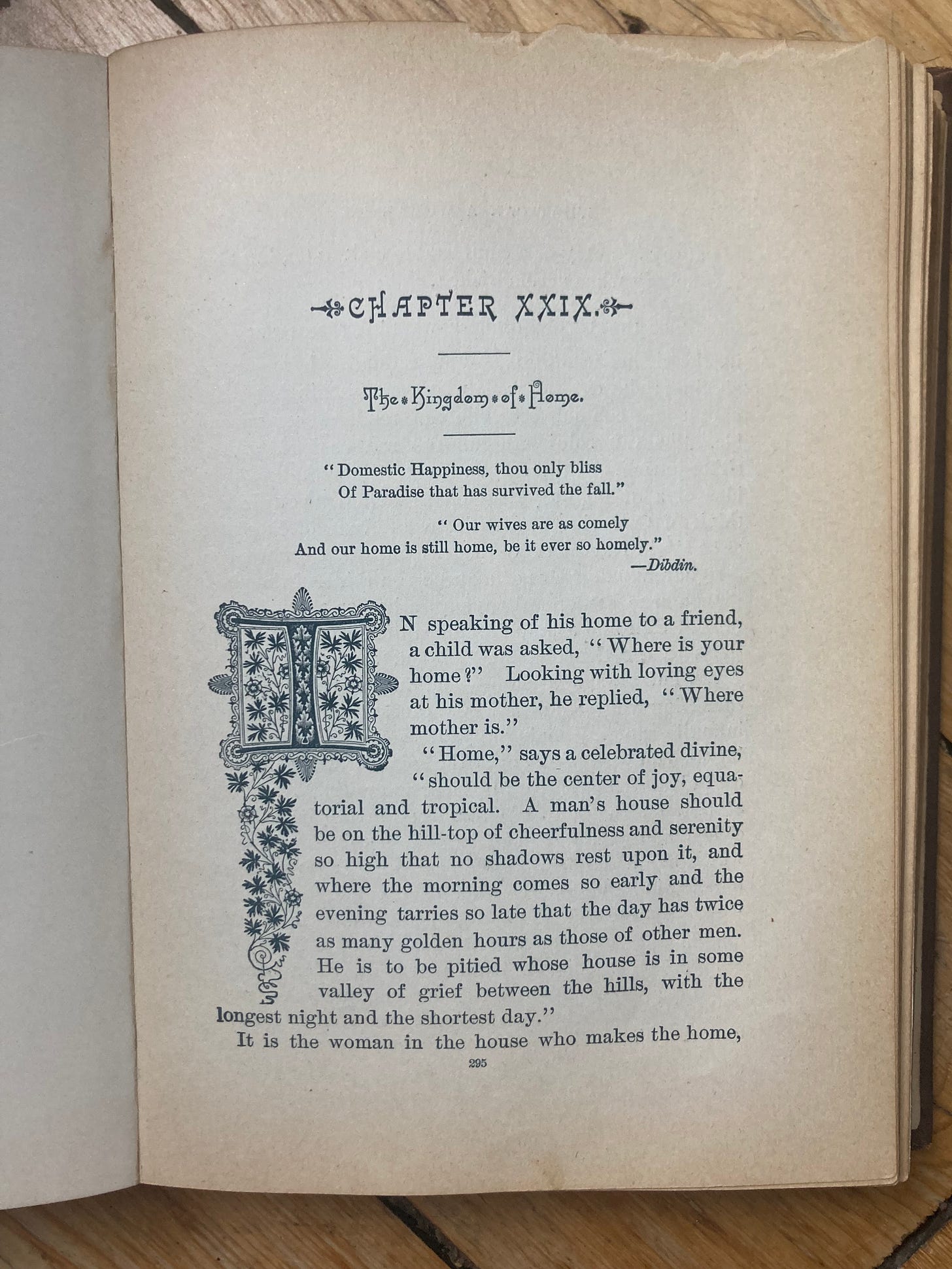

What Can A Woman Do? has bold suggestions for women, but steadily reminds them to maintain their womanliness, and to not stray from their natural work in the home. This reflects the prevailing and conflicting sentiments about American women’s work and lives circa 1884 (first edition) — 1893 (my edition). She lists a slew of prospects, encouraging women to work hard, yet never loses the standard tune a woman must play, singing the songs of HOME.

“Home means so much in this nineteenth century,” Rayne writes. “It means all that makes life really worth the living. It means comfort, affection, sympathy, confidence, consolation, encouragement, rest, and peace. It is the object to which all unselfish endeavor is directed. When the head of the family returns home at night, after a weary day's endeavor, he is at once wrapped in a familiar atmosphere of comfort. All is bright, clear, warm, happy, and it is all woman's invisible work. It was she who arranged everything, brightened everything, placed necessary things ready to hand, and removed useless ones. The man of the house never saw her do these things — never will see her do them. He is always absent when the household elves are busy. He is content without knowing why — without a thought of the thoughtfulness and constant labor required for his comfort.”

Women manufacture these feelings with housework, and Mrs. Rayne promises consolation for invisible, endless chores would come once she met her creator. Then she would find her ease.

Such lofty stuff is spread throughout the employment section — and peppers the second half the book, which is a literary anthology. Many of the jobs and examples she lists revolve around the home: raising poultry, flowers and food to sell, running a boarding house – all of which can help catch a woman when her fortunes reverse, and she needs to earn.4 Sewing and dressmaking must, she cautions, be pursued with education, either through an apprenticeship, or a remote course to build skills. Limping along by instinct is a dreadful habit, she writes here, and in the chapters on scientific cookery and domestic management. She has harsh words for married women to pay ‘a girl’ to do heavy work so that she can avoid becoming “a peevish, dissatisfied, faded woman, whom it is a trial to live with.”

Chapters on making money in the home were mixed with advice on how to run a household with paid help. She mentioned cooking schools in Boston and New York as a good way to train servant girls but said the best school for an ignorant (!) girl was the kitchen of a kind and intelligent mistress “who is willing to spend a large part of her life in that best missionary work — training Irish and German girls in ways of thrifty housewifery.”

Soon after this insult, Rayne glorified bread making, and quoted a letter Mrs. Lucretia Garfield, widow of the president, wrote to her husband.

"I am glad to tell you, that out of all the toil and disappointments of the summer just ended, I have risen up to a victory; that silence of thought, since you have been away, has won for my spirit a triumph. I read something like this the other day: “There is no healthy thought without labor, and thought makes the labor happy.” Perhaps this is the way I have been able to climb up higher. It came to me this morning when I was making bread. I said to myself, “Here I am compelled, by an inevitable necessity, to make our bread this summer. Why not consider it a pleasant occupation, and make it so, by trying to see what perfect bread I can make? It seemed like an inspiration, and the whole of my life grew brighter. The very sunshine seems flowing down through my spirit into the white loaves, and now I believe that my table is furnished with better bread than ever before; and this truth, old as creation, seems just now to have become fully mine, that I need not be the shrinking slave of toil, but its regal master, making whatever I do yield its best fruits.' "

Because this bread-brow-beating isn’t enough, Rayne stacks more obligations onto this basic food, kneading her ideas into a frenzy:

“Give us this day our daily bread," is one the beautiful petitions of Our Lord's Prayer. How often have weary souls longed to add, with all due reverence “Give it to us white and light and sweet, wholesome and digestible, that we may be comforted and strengthened." The meaning of the word lady is loaf-giver. Can there be a more acceptable priesthood than this service of love and labor — the token of hospitality— the badge of ladyhood? Some one has curtly said that it is not passion or ill-temper that drive men to commit murder or suicide; it is heavy, sour bread, which perverts the whole current of being, and transforms human beings into demons. Every woman has a mission to learn to make good bread, if she would consider the happiness of her family.”

WOW! Bread absorbs ideas and ideals! But we knew that, right?

Butter my slice with many grave warnings, please. I am a woman, and I swear I’ll keep folks from murder, and prevent my family from becoming demons, just by baking bread. Pardon me, I’ve got some dough5 – I mean individuals and a society – to wrangle in the kitchen.

Yours, Amy

Mrs. M.L. Rayne started a journalism school in Chicago.

The author attributed this segment to the Bellevue School of Nursing. Though other information in the book was distilled from other writings, Rayne rarely named sources.

I wrote about bread ideals in the 19th century, and about Laura Shapiro’s excellent writing about women here.

This overlooks race and class. The women in my past were white, but they always needed to earn.

Adrian Hale is a friend, and fellow writer and educator. Please take a look at her website — especially when you are traveling and want to know where to find fresh flour and good bakeries. Consider buying her wonderful book, Mama Bread for more simple sourdough lessons.

This is the recipe I generally use, and all the notes are hers.

Communal Bread

We live in an imperfect world. At any rate, perfection is not what we’re after. What we want is to live in a harmonious community and that’s what this bread wants, too. So let’s work together to make something imperfect that finds a way to be both nourishing and tasty, despite differences…no, BECAUSE of differences.

Try this bread with what’s on hand and let me know what you think. I provide volume measurements for this recipe, but I highly recommend trying to find a scale and measuring by weight. You’ll get better results and more consistency. I’ve tested this with many kinds of flours, and while there were slight differences, all had good results.

850 grams water (3 ½ cups)

50 grams sourdough starter (¼ cup)*

20 grams honey or sugar (1 tablespoon)

20 grams oil or melted butter (1 ½ tablespoons)

1000 grams whole wheat flour or a mix of all-purpose w (9 cups)

20 grams salt (1 tablespoon)

Mix the water, sourdough starter, honey, and oil in a large mixing bowl. This doesn’t have to be fully incorporated, but simply mixed together a bit. Add the flour and salt and mix until there are no visible dry pockets of flour. Cover with a wet towel or a plate and let this mixture rest at room temperature for 8 to 12 hours. I often do this overnight to shape in the morning OR I’ll mix first thing in the morning to shape when I get home from work in the evening.

After its long rest, fold the dough by grabbing the edges of one side and folding it towards the middle. Do this all the way around the bowl until all the edges are folded towards the middle. This usually takes about 4 to 8 folds around the bowl, depending on the flour. The folds de-gas the dough a little and provide a bit of structure for the shaping. After the folds, let it rest for 30 minutes to 1 hour. If you don’t have time, simply go straight into shaping.

To shape, you need to make some choices. This recipe makes 2 loaves or 16 flatbreads that can be used for pita or pizza or grill bread. To make the loaves, cut the dough in half. If you’d like to make one now and one later, put the dough you aren’t going to bake into a container in the fridge and hold there for up to three days. It will get more sour over time, but still be perfectly tasty as the days go on.

For making the loaves now, preshape them by patting out the dough into a rectangle. With the long side of the rectangle vertical to you, fold the top towards the middle, then the bottom up with a little overlap. Next fold the left side in and then the right side, also with overlap. This process will make a seam, which is the bottom of your loaf. Flip it over to rest 5 to 10 minutes with this seam down. Get your loaf pans ready while it’s resting: butter or grease the bottom and sides of two standard size loaf pans. For the final shape, turn the seam side up again with the seam running vertical. Refold the top down and the bottom up with overlap. This time, instead of folding the left and right sides in, roll the dough from left to right into a kind of jellyroll shape and place the seam side down in the prepared loaf pan. Cover these pans with another loaf pan or a tent of foil.

Proof at room temperature until the loaves gain enough volume to fill the pan; the tops usually reach just over the lip when I put them in the oven. About an hour into the proof, heat the oven to 450°F. When the loaves are finished proofing, bake them for 40 minutes total, keeping them covered for the first part of the bake and uncovering them for the last 20 minutes. Pop them out of the pan and let cool at room temperature.

To make flatbread, pita, or pizza dough, cut the dough in half (you can make one half into a loaf and the other into pita and pizza if you desire). Cut each half into eight pieces of relatively equal size. Shape each piece into a ball. Cover and let rest for 30 minutes to 1 hour. If you want to save some of these for later, put them on a baking sheet and store in the fridge for up to 3 days. For longer storage, put them on a sheet pan in the freezer and flash-freeze until solid, then transfer to a bag for easier storage. When you’re ready to make them, bring to room temperature.

For pita, preheat the oven to 500°F. If you have a baking stone, put it in the oven, or you can also use a baking sheet. Pat out each ball into a round. You can use your fingertips and palms to flatten this out, loosening the bottom of the dough now and then from sticking to the table. Use flour liberally and flip the round from time to time to keep it from sticking. When the dough is well flattened, shake off the excess flour and put the rounds into the preheated oven.

Let cook about 5 minutes until they puff up and then flip for another minute or so. Eat hot out of the oven, or soon after. They’ll save in a ziptop bag for up to three days. As they stale, make them into chips! For pizza, I find it best to roll this out with a rolling pin until pretty thin. Transfer to a pizza pan or baking stone and proceed with the toppings of your choice.

*If you don’t have access to a sourdough starter, you can substitute a pinch (¼ teaspooon) of instant yeast, but I highly recommend for purposes of both health and tastiness, that you find someone to share their sourdough starter with you.

I have achieved it… The Profession of Literature 😭

Such excellent and INTERESTING research, Amy. The title is so perfect. I love the whole “lady” designation, reminds me of the “Board of Lady Managers” at the 1893 World’s Fair!