Dear Bread Fans,

Earlier this month, before the oligarchy really began slicing and dicing America, I gave a talk about the history of my local YWCA to the League of Women Voters in Rensselaer County. I have been felled by a cold, and emotionally stifled by the facts of this regime, but I’ve finally put together a recap of my talk.

I welcomed the chance to revisit the YWCA-GCR archives -- like rereading a favorite book, you always find something new. This time, I was looking at the organization’s records to think about what empowerment has meant in the Y over time, and how that work can inspire us to serve our best asset: our communities.

If you’re a new reader here, you’ll want to know that my city of Troy, New York made 90% of America’s detachable shirt collars and cuffs in 1900. Much of this manufacturing – sewing and starching – was done by women. Troy was a City of Women, with one in three women working beyond their household obligations. This workforce was primed for the entrance of Freihofer’s, a Philadelphia bakery that found us as they were traveling to Montreal to look at ovens.

The Young Women’s Christian Association started in England in 1855 and the United States in 1858, to serve young women who were moving to cities to work in factories. The Young Woman’s Association (YWA) began here in Troy, New York in 1883 as an independent group of concerned citizens, and became a member of the national YWCA in 1915.

I have mixed feelings about the monied women who began these endeavors. I’m suspicious that the sins of the industrialists could be removed through their wives’ and daughters’ good works. But, even if I’m looking at history with contemporary morals, what’s so awful about rich people creating social structures?

In Troy, women led the way to make orphan asylums, hospitals and homes for the aged poor. There were lots of temperance societies to help steer dollars out of bars; there were a couple of day homes – nursery schools – to tend to kids while mothers worked for pay.

The Young Women’s Association began with rooms that were open in the evenings to offer hospitality and classes. Soon, the need to also provide housing was met – the YWA had its first home at 43 Fourth Street in 1888. In that year’s report, the association described their beginnings:

“Ten thousand girls and women are employed in the shops, stores and factories of this city; these, dependent upon their own resources, many of them coming from the country are deprived of the comforts and associations of home, its blessings and sanctities. This separation from home, friends and church is often the turning point in their life, the time when kindly influences are most needed, when those little nameless acts of kindness are a benediction to the recipient. Here they crowd into boarding houses without restraining or elevating influences… The character of a community depends much on the young women…if the young women are frivolous and reckless, the young men will be dissipated and worthless…”1

The report cited the long work of the Young Men’s Christian Association and argued that young women needed equal guidance. “Ever is the city a great tempter to the young of both sexes.”

The Young Women’s Association’s services were essential to saving the futures of women and men. These moral goals were undertaken through classes in embroidery, elocution, stenography and typewriting, calisthenics, penmanship, bookkeeping and dress cutting. Cooking classes were elaborate. I was excited to read that the YWA hired Miss Barnes for a whole month of instruction, during evenings in November. The report noted that she was a graduate of the famed Boston Cooking School and a pupil of Mrs. Parloa, who at the time far more famous than the name readers may link to this school – Fanny Farmer.

Other activities included a Women’s Exchange, where Troy women could consign things they made – from canned goods and cakes to socks and other clothes. I was excited to learn we had a Women’s Exchange! Exchanges were commercial/community enterprises formed after the Civil War, as a way for war widows to support themselves. I learned about them in the 1990s in Baltimore, when I ate crab cakes and coconut layer cake at their Ladies’ Industrial Exchange in their oh-so Gilded Age dining room. The bentwood chairs felt like they’d break underneath us, but the décor felt more firm in its frilliness. Upstairs, in their shop, I bought a blue velvet wizard’s hat, telling myself I’d use it for storytelling at the library – a fantasy act I never realized! The Baltimore Ladies’ Industrial Exchange is sadly no more.

In Troy, the exchange and the success of the cooking and other classes argued the case for a larger building, and fundraising began. Throughout the city, people and businesses ponied up. An 1891 register shows a range of donations – from individuals giving a dollar or two, to the city’s breweries giving $50 or $25. Collar and cuff factory owners gave larger amounts, multiple times. One of the biggest contributions from a business was the Singer Manufacturing company: $1000. I was surprised to see that the sewing machine company had such a presence, though of course it made sense, with all these enterprises reliant on sewing. The YWA planned on the sale of their first building as a good chunk of change, but the bulk of money to make the building a reality came from the largest collar company families.

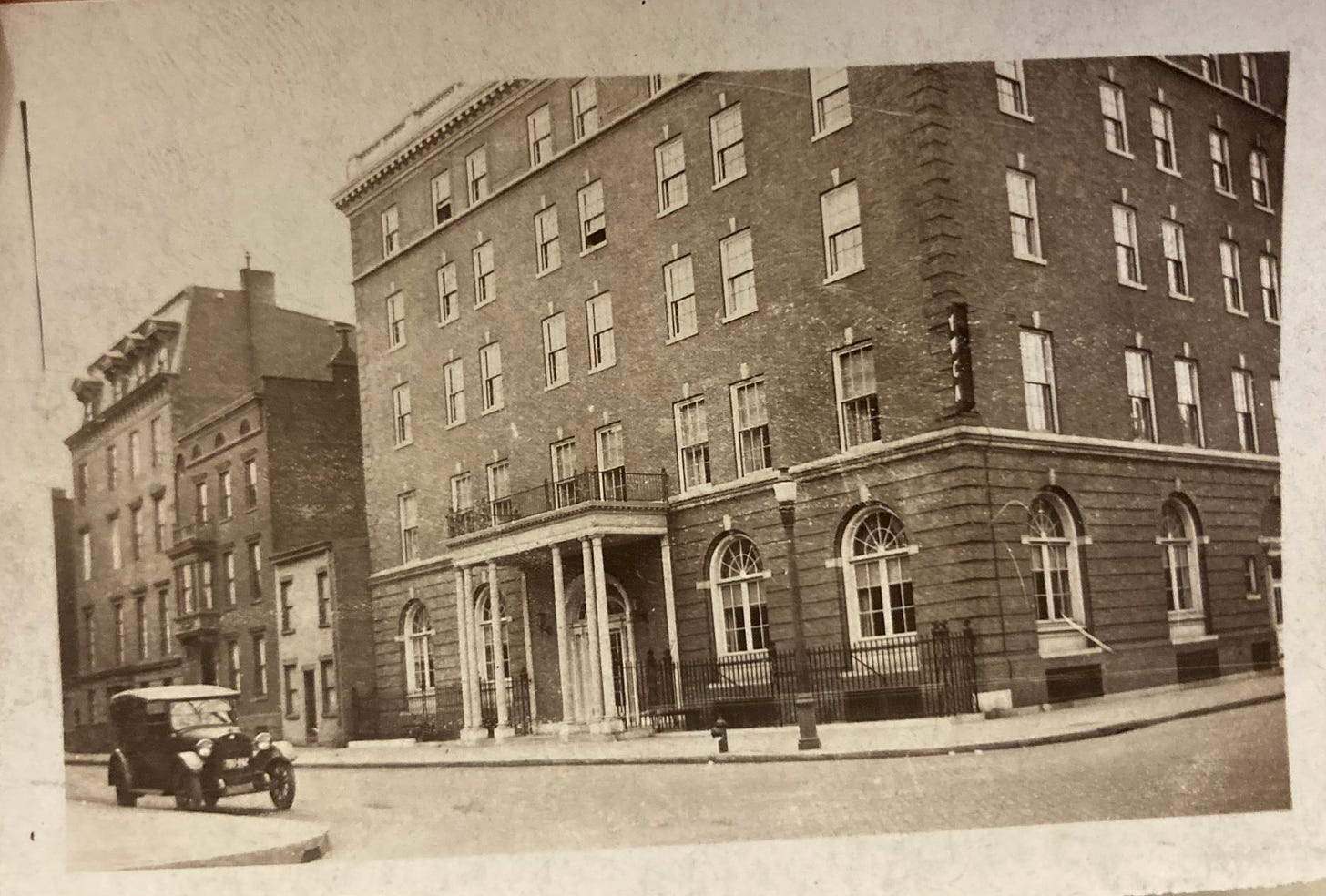

The YWA built a broad, handsome brownstone in 1891, describing their new building as, “an ornament and monument to the liberality of Troy’s citizens – a home for its working women… offering refuge, rest, education, companionship, and recreation. With 54 light, well-ventilated sleeping rooms, luxuriously warmed in winter and most comfortably furnished with every requisite; with hot and cold baths on each hall floor; with a spacious room furnished for a library, two cheery reception rooms, a large and attractive auditorium for class work and entertainments, with well fitted and spacious classrooms for the evening classes, it really seems there is nothing left to be wished for or desired…”2

Soon, they would eat those words. Within a decade the building outgrew itself, and ideas of a new structure, especially one with a swimming pool and gym began.

Other Troy institutions were blooming. Our glamorous public library, with stained glass windows and an elegant marble staircase, begging for dances and ballroom dresses, but really, just escorting the idea of self-edification with a swoop up to the second floor, opened in 1897. The Troy YWA joined the national YWCA in 1915 – the Cohoes (a nearby city with its own textile history) branch joined earlier. The Troy YWA was resistant to merging because some board members didn’t want to be strictly Christian in overtones – even though they defined their work in Christian terms, a few found the national organization’s strictures limiting. As progressive as this group was, everyone was working within their times – and ideas about women were stalled, not just in terms of what others thought of women, but in what we thought of ourselves.

This era – the turn of the 20th century – really intrigues me. It’s what I’m looking at in my next book, the twinned histories of the modern American woman and the modern American loaf. Believe it or not social concepts about each of these products were linked. The battle for who should make the American loaf, a sainted mother or a sanitary factory, played out an ideological war about what women could and should be.

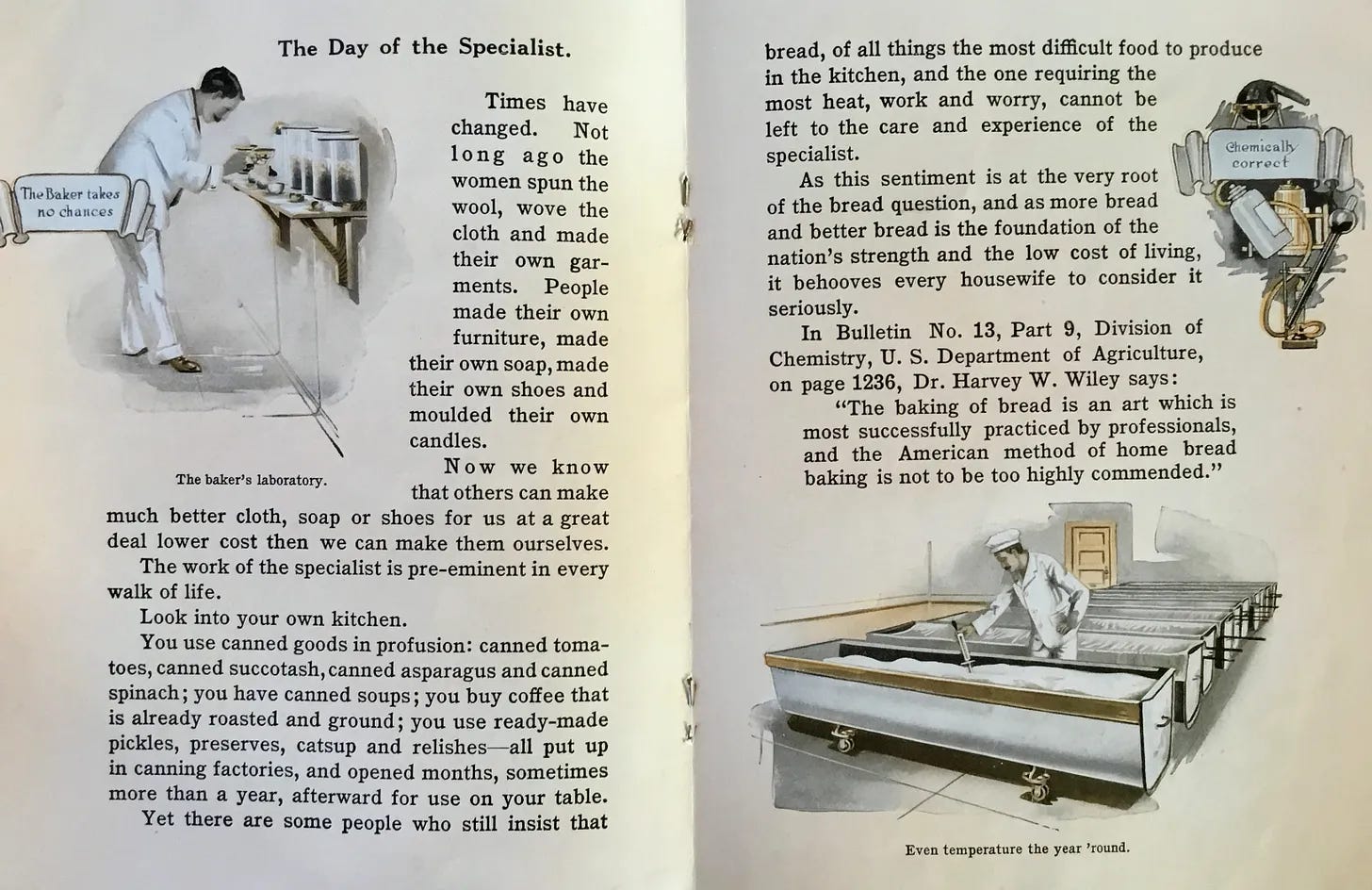

The 19th century promoted an idea of white women as keepers of the home fires and makers of one of the most valuable commodities in the new republic: proper citizens! Bread, lovingly made at home, was one of the emblems of a woman’s – a white, middle and upper class woman’s – work. She could help make good Americans by making bread. This was so firmly entrenched in the public imagination that as factory baking emerged, the homemaker was seen as the industry’s biggest competition. “More time mother’s reading comes from less time mother’s kneading,” the national trade organization for bakery owners promised. Below is a pamphlet members distributed to their customers to argue for Bakers’ Bread. (I wrote about this at Wordloaf.)

This was part of a broad dialogue about modernity. Newspapers were running columns questioning the “New Woman” and her man-hating ways. Reading through the Troy YWCA-GCR archives, I found the argument locally expressed. At a 1917 meeting, Mrs. Van Nostrand spoke about “the worthwhile woman.” There are two ways of looking at woman's position, she said.

“The old days were the best days, and second, that the old-fashioned things must give way to the modern idea that things are right as they are today. The olden days were when a woman's sphere was limited to her home; when laws were made by men by which women were governed: when the marriageable age was 15 and after 40 they were declared old women to sit by the fire and knit; when the home, babes and him was the slogan of the wife and mother.”3

The speaker questioned whether women were honored by men in the olden days. She said that a few women heard the call of God out into a different life. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Jenny Lind, Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton, Queen Victoria were not content to sit by the fire and knit.

“The feministic movement has spread throughout the world, and it has been proved that women are the equal of men mentally,” she asserted, yet women are not matching men in inventions. That’s because in addition to her new duties, “the woman must also take care of the home, the babes and him and her mind is seldom free enough to do the close research work necessary for invention.”4

Again, these statements are from 1917, a year that suffrage was defeated. It's also the year that we entered World War One, and the cornerstone for the new YWCA building was laid at the corner of First and State Streets. This building was also significantly funded by collar industry families.

It’s worth noting that pro and anti-suffragette peoples were united in supporting the YWCA. Some of the elites were decidedly against voting rights for women and some were for it, but everyone's saw the necessity of continuing to support working women in Troy. I appreciate knowing this unity and learning more about this model of service for the greater good. The Y and the League of Women Voters are pillars we need to lean on in rough times.

Yours, Amy

NOTES:

The YWCA kept operating its building on Second Street for quite a while, until they sold it to the Christian Scientists for a reading room. Throughout the century, the shape of the work, on a national and local level, have changed. The YWCA-GCR (Greater Capital Region) is, as its mother organization is, committed to eliminating racism and empowering women, and rededicating itself to this mission and tasks as situations demand. The YWCA-GCR was a prominent voice and supporter in keeping the Burdett Birthing Center open – this city and county’s only maternity ward. This is no small victory in this era of corporate dominion.

The local papers for the YWCA-GCR are housed in paper at the Hart Cluett Museum, and I’m grateful to help from curator/archivist Sam Mahoski and director/historian Kathy Sheehan for help in preparing for this talk.

I am working at Hart Cluett as writer in residence for the first half of this year, thanks to an Art Connects grant, which is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts & New York State. I wrote about the beginning of my research at our local newspaper, the Times Union. Read that here. Very grateful for the Arts Center of the Capital Region, which administers this and other grants programs.

The national organization’s records are at Smith College, and some of them are digitized and available online. These are a really fascinating way to look at what was happening at a local level, from the national perspective!

I’ve been working with YWCA-GCR staff trying to interpret the history of the organization and the building. With the fabulous poet and artist D. Colin, we looked at Black life and racism in Troy. For each of these events I wrote pamphlets that are now available, digitized and downloadable, on the homepage of the website. We held the first annual International Women’s Day luncheon last March, and are gearing up for another on Saturday, March 8th. If you are near Troy, save the date!

I used to I wish that Troy and Cohoes had, like the textile factories in Lowell, Massachusetts, good-hearted overlords who established learning opportunities for their employees. Even though we didn’t have idealistic boarding houses, we had the Young Woman’s Association! If you are curious about mill life, Katherine Paterson wrote a great novel called Lyddie about a farmgirl in Lowell.

I have been fortunate to have several state grants to study pieces of the past. These state monies are always tied to the federal government. I wish the funding streams in our country — for the arts and so many essential services — were not getting severed. My family is filled with teachers. What’s happening is terrifying.

1888 Young Woman’s Association annual report, Troy, courtesy Hart Cluett Collection.

1891 Young Woman’s Association annual report, Troy, courtesy Hart Cluett Collection.

1917 Young Woman’s Christian Assocation annual report, Troy, courtesy Hart Cluett Collection.

1917 Young Woman’s Christian Assocation annual report, Troy, courtesy Hart Cluett Collection.

This was really interesting to me. I especially liked the quote about reading taking from kneading! I recommend to you the book The Woman They Could Not Silence, by Kate Moore. Men used to be able to lock their wives in an asylum for disagreeing with them, for thinking too much, etc. While Eliz. Packared, the subject of this book, made a sanity trial required for any commitment, this punishment of women for reading and thinking continued well into the 20th Century--think Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Virginia Woolf.

It was fascinating to read about your local history, particularly the YWCA. I admit, I don't know too much about either the men's or women's version of this institution. It seems that they're both primarily fitness centers now, not that there's anything wrong with that! But it was enjoyable to hear that your Y had so much more once upon a time.

And congrats on the position at the museum! It sounds fascinating. It seems like you have a quite a talent for finding opportunities to further your knowledge, while getting paid to do so. You mentioned needing three tries to graduate from college. Well, I feel you missed your calling in a way...you clearly have the mind of an academic, so you would have made a fine college professor! (I say this with all sincerity, as I happen to be married to one myself).

Was sorry to learn that the Baltimore Women's Exchange is now closed. After having read of it via Jane and Michael Stern, we ate lunch there once. After our meal I bought a keychain with a miniature stuffed cat attached to it to gift the neighbor girl who was watching our cat during our travels.

Lastly, with some sadness I report that our daughter is flying back to Michigan today to begin a new job next week. She lost her job in the Albany area in early November. Although she'll now be 160 miles away instead of 900, my husband and I are actually bummed about her leaving your area. There's so much to see and explore and we'd been looking forward to doing more of that in future visits. She tells us we can still go back there to visit, which is true, but I reply that we'll no longer have free lodging to take advantage of.

I wish you all the best with your writer-in-residence research and look forward to reading what you uncover.