Dear bread,

I want to learn your history. I’d like to understand each American loaf — bread circa 1670, 1770, 1810, 1830, etc. — as if there were ever only one bread that settlers ate as we took over this landmass. Wheat bread history begins with colonization, because wheat is not native to the Americas. My curiosity is narrow, shaped by the tendency to take what we have and use it as a mirror that casts backward. The past was now-ish, right? No. Every layer of time and place has a million variables. How can I ever know what you were, dear bread, bread dear?

I can barely guess what my neighbor thinks, let alone my siblings, and we shared the same family. How can I expect to learn about the past, and begin to get an estimation of what was?

This summer, The Gilded Age was filming again in my city. Tractor trailers filled the streets and alleys, holding generators and snaking giant HVAC hoses inside buildings to sweep the air per Covid protocols. What if these tubes were time machines, and we could swoop back to the late 1800’s? Taste the bread? Bake the bread? I imagine I’d be a servant, and perhaps I’d use one of Mrs. Lincoln’s recipes to guide my kitchen work.

Maybe —if these time machines I’m imagining went to Troy, instead of NYC as the TV series does — instead of lurking about life, taking notes, I’d be making detachable shirt collars and cuffs. There were 30 collar and cuff manufacturers, and loads of women did piecework in their apartments, rather than sewing at a factory.

Maybe I’d be a launderer, washing and starching the goods after they were sewn. (This was grueling work, and inspired the first successful women’s union in America, Kate Mullany’s Collar Laundry Union.)

What would sustenance look like for a working woman and her family in the late 1880s? Would I bring a baked potato for my lunch? Would I have an oven to bake my bread on Sundays? Would I buy bread from someone in my neighborhood, either a small bakery or from someone who baked in the back of her house? Perhaps I’d eat crackers, because they stayed fresh longer than bread.

The possibilities of the past shine like diamonds, not because time was older and the days were good, but because the days are gone and I crave evidence. One of my favorite what if’s is looking at city directories, which listed residents and businesses. Here’s a page from the 1888 Troy city directory, from awning makers to bankers.

As a kid in the 1970s, I fell in love with history. When my parents stripped the walls of our house down to plaster and lath, I wanted to find a letter from Abe Lincoln. It didn’t matter that we lived in upstate New York, nowhere near Illinois. I was growing up and changing, time sliding through my life in exhales and outgrown clothes. Our backyard burped up trash from the early 1900s, cobalt blue medicine bottles, a porcelain doll head or arm, rusty horseshoes. Once we found an entire champagne bottle, making the past seem near enough to touch.

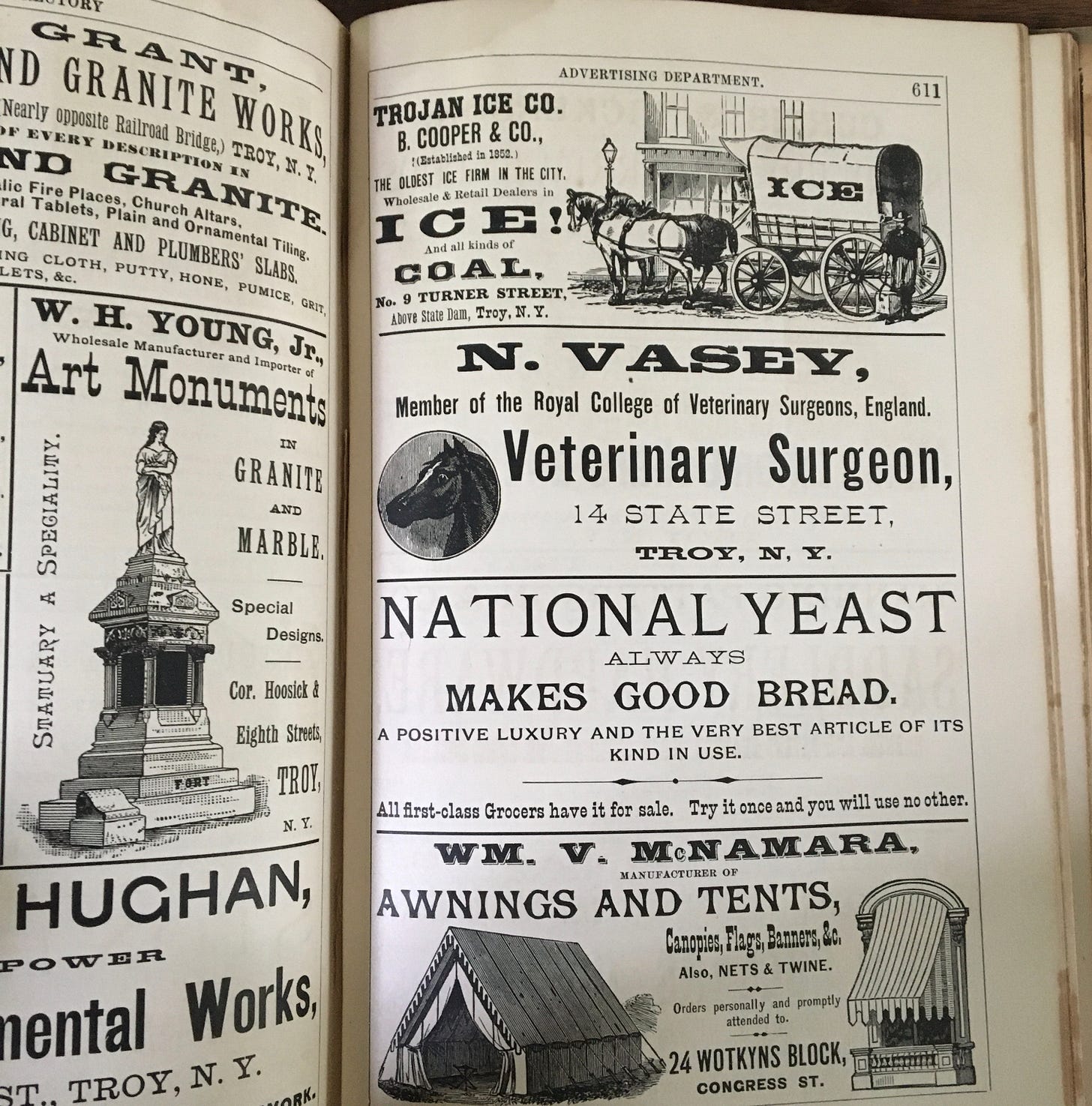

The past is much closer now that I’m 55. The finitude of my own life strikes me, and time seems less capacious. I remain starved for artifacts, and I wonder what they can offer beyond nostalgia. Look! I marvel. This was! And now this is? I don’t know why all the if’s intrigue me. I think the American Bicentennial frenzy is part of it, but some of us just love old stuff. Nothing tells me how we got to 2022, an unbelievably hot summer, but I sure like to look at bread clues. Here’s another page from the 1888 Troy City Directory.

Of all the advertising on the above page, the one for yeast is the only general ad — everything else is for a specific enterprise.

“National Yeast always makes good bread. A positive luxury and the very best article of its kind in use. All first-class Grocers have it for sale. Try it once and you will use no other,” reads the ad.

Yeast was patented in 1868 by Fleischmann’s, and 20 years later, it looks like people needed encouragement to use this novel product, rather than making some type of yeast themselves, as many cookbooks instructed. (Linda Civitello’s The Baking Powder Wars is an excellent read on leavening in America. I wrote about it here.)

Given my wonder about the past, I should be excited about The Gilded Age taking over my city, but it breaks my heart. For more than a year, I tried to land an essay about the incredible expense that goes into reimagining the past for this and other films. I’d rather we, as a society, invest in the present and future. More than a quarter of my city’s population lives under the poverty line, and rents are soaring because of gentrification. The filming is fun, but it doesn’t help address the widening socioeconomic divide, here or else where.

Troy is at the top of the Hudson Valley, and New York State and its municipalities have economic development plans & folks luring the film industry to use us. Screens seem to be where America’s energy for social transformation lies. Clearly, there is a will to see and pay for another reality than the one we have. How can we begin to invest in visions of everyone thriving rather than fictions of other eras? The past has value, but we don’t have the right mindset to use it for the greatest good.

One use of the past I love is the Reher Center in Kingston, NY, and the work they do with the history of work, immigration, and baking. A new exhibit on bread is opening today, and I interviewed Sarah Litvin about all things Reher at Heritage Radio Network’s Catskills Field Day.

I am ever gathering more resources to understand baking history. Do you have books & other media to recommend? Please let us know.

Yours, Amy