Flour

What old cookbooks say about my favorite ingredient

Dear Flour Fans,

I hope you are baking up a storm to bake away the storms that we’ve had this month -- if you’ve had power and clean water and time to do so. Texas, oh my, I wish all of that had not happened; if you have resources to share, World Central Kitchen is one organization that’s helping.

Flour has been on my mind, as usual. Recent dialogues Andrew Janjigian and Alicia Kennedy had on their newsletters were really wonderful, and covered aspects not generally touched in either news articles or food media, such as the challenge of writing recipes for national audiences and needing to write those recipes with easily accessed ingredients. Andrew’s term ethical flour really resonates with me, getting at the values behind the products of small mills and regional farms I support. Of course the term fancy flour also fits, but doesn’t reflect the goals I’ve seen expressed by bakers, millers and farmers working to create food that differs from the products of the dominant, commodity grain system.

A lot of ideas bubbled up inside me when I read what Andrew wrote -- he also penned a follow-up piece. I want people to be able to slide easily from the flour they know into these ethical/fancy/alternative flours and so I suggest people start off with pancakes or crêpes. Pretty much any flour is going to go kindly to the griddle, and reward your breakfast. Yet I also have some magical thinking about the interchangeability of flours from small mills. I think the wishing sprouts from my wanting everyone who bakes with these ingredients to have success; with success, the home bakers will have similar affection for the people growing the grain and milling the flour.

Yet Turkey Red from Eastern Washington is going to be different from Turkey Red grown and milled in Illinois, and these differences should be a delight, not a barrier! I can’t make generalizations that will help you use any and every flour from any and every mill. So please take a look at info from Grist & Toll, Groundup Grain, Meadowlark Organics, Bluebird Grain Farms, Barton Springs Mill & Janie’s Mill to get an idea of how mills are communicating what’s going on each bag, and what that will mean for your bowls.

Way back in the 1800s, when differences in flour were common, because of seasonal fluctuations affecting how grains grew, and the varying characteristics of each mill, bakers didn’t have these virtual encyclopedias to consult. Experience was a great teacher, and people learned how to handle flour by handling flour. Eventually, cookbooks began to articulate information to get home cooks comfortable with interpreting this untamed ingredient.

Miss Parloa’s Kitchen Companion: A Guide For All Who Would Be Good Housekeepers (1887) and Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book: What To Do and Not To Do in the Kitchen (1883) open windows on an era when flour milling was changing dramatically.

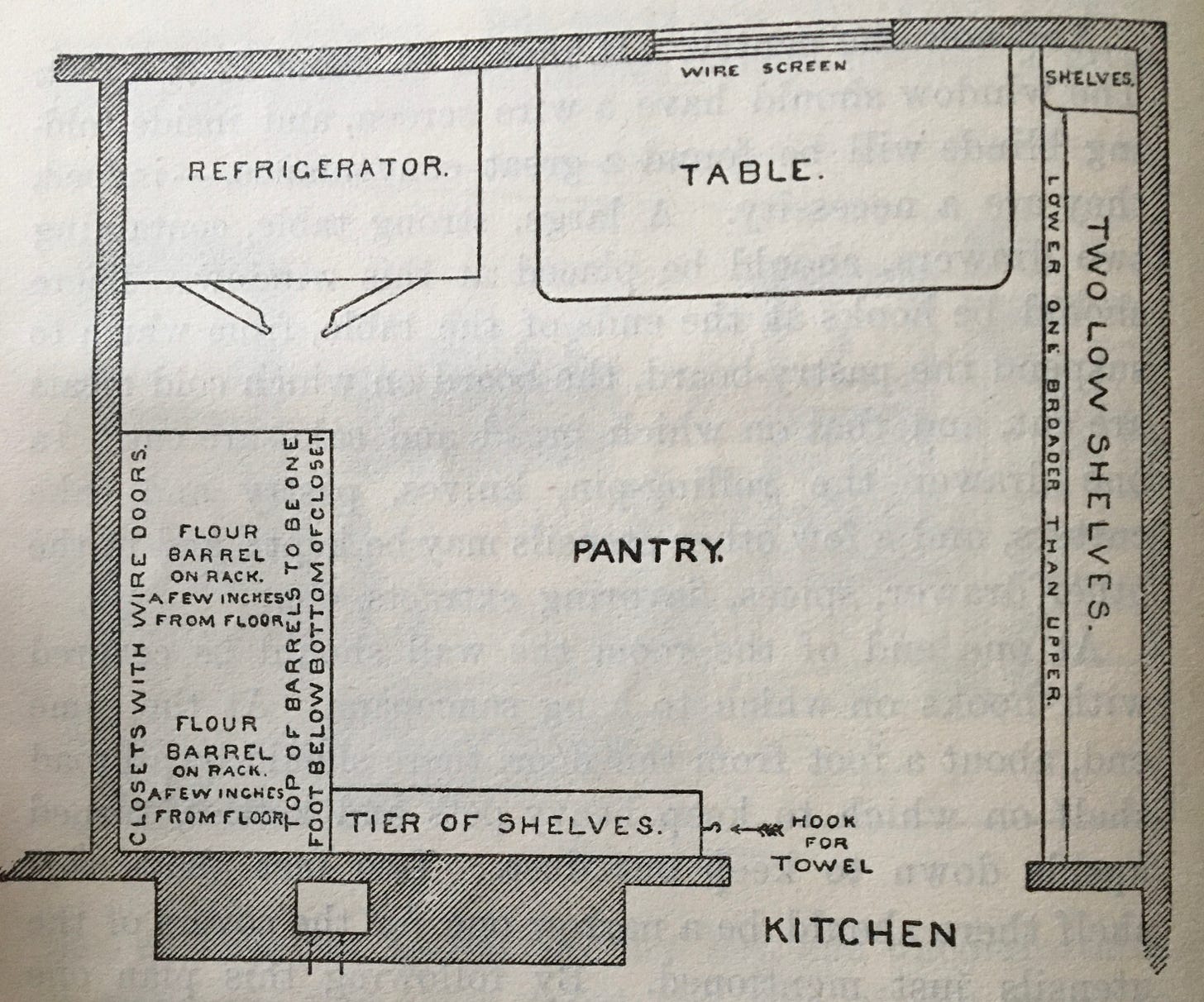

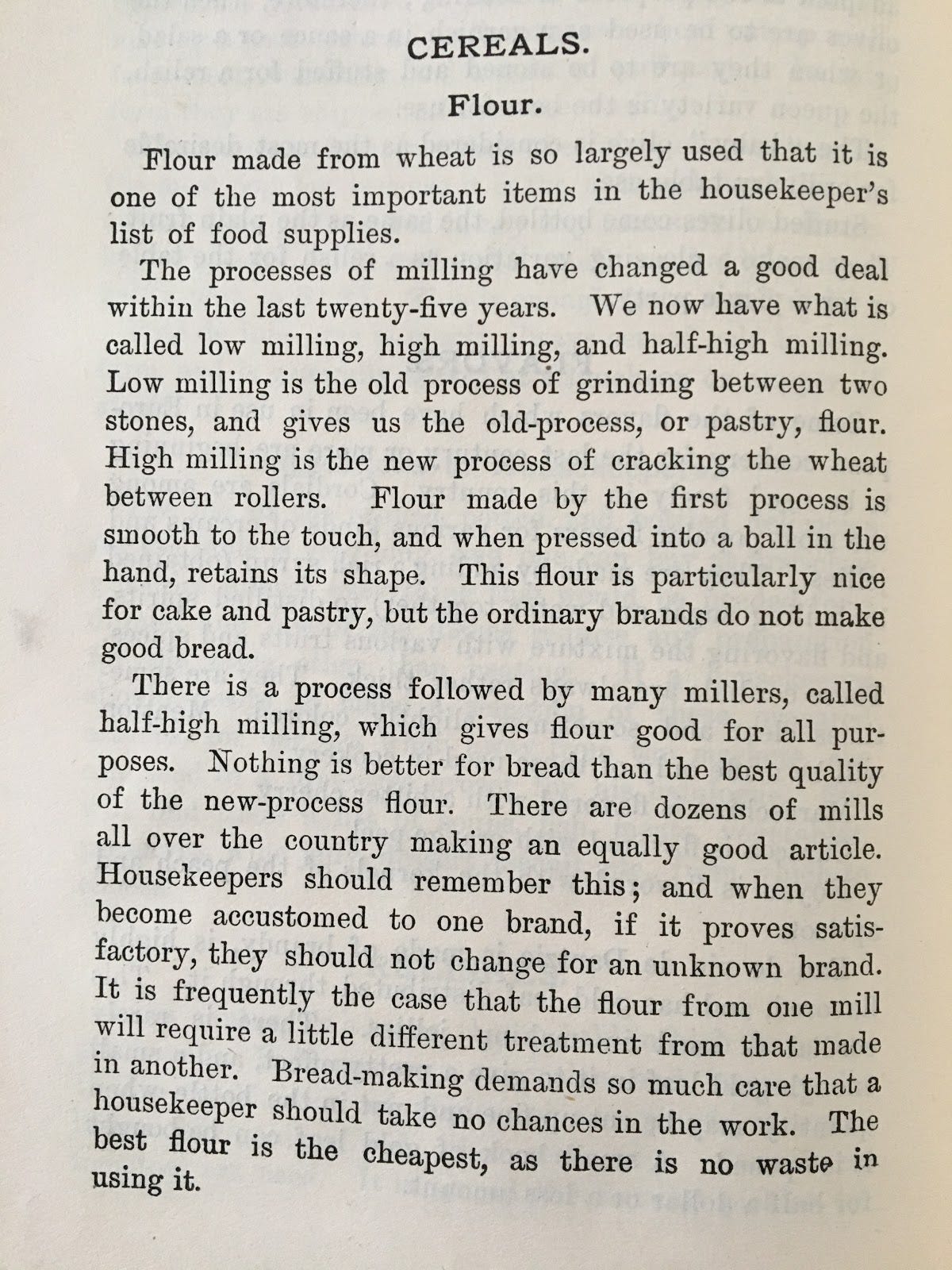

Miss Parloa even detailed how flour should be stored, above, diagramming the ideal pantry setup. Below is how she described flour and flour milling.

This last line, that the best flour is the cheapest, seems at odds with the previous line, that no chances should be taken with the work. In later pages, Miss Parloa discusses poor quality flour and the need to avoid it, and laments the good old days of cornmeal, when corn kernels were not kilned, but dried naturally.

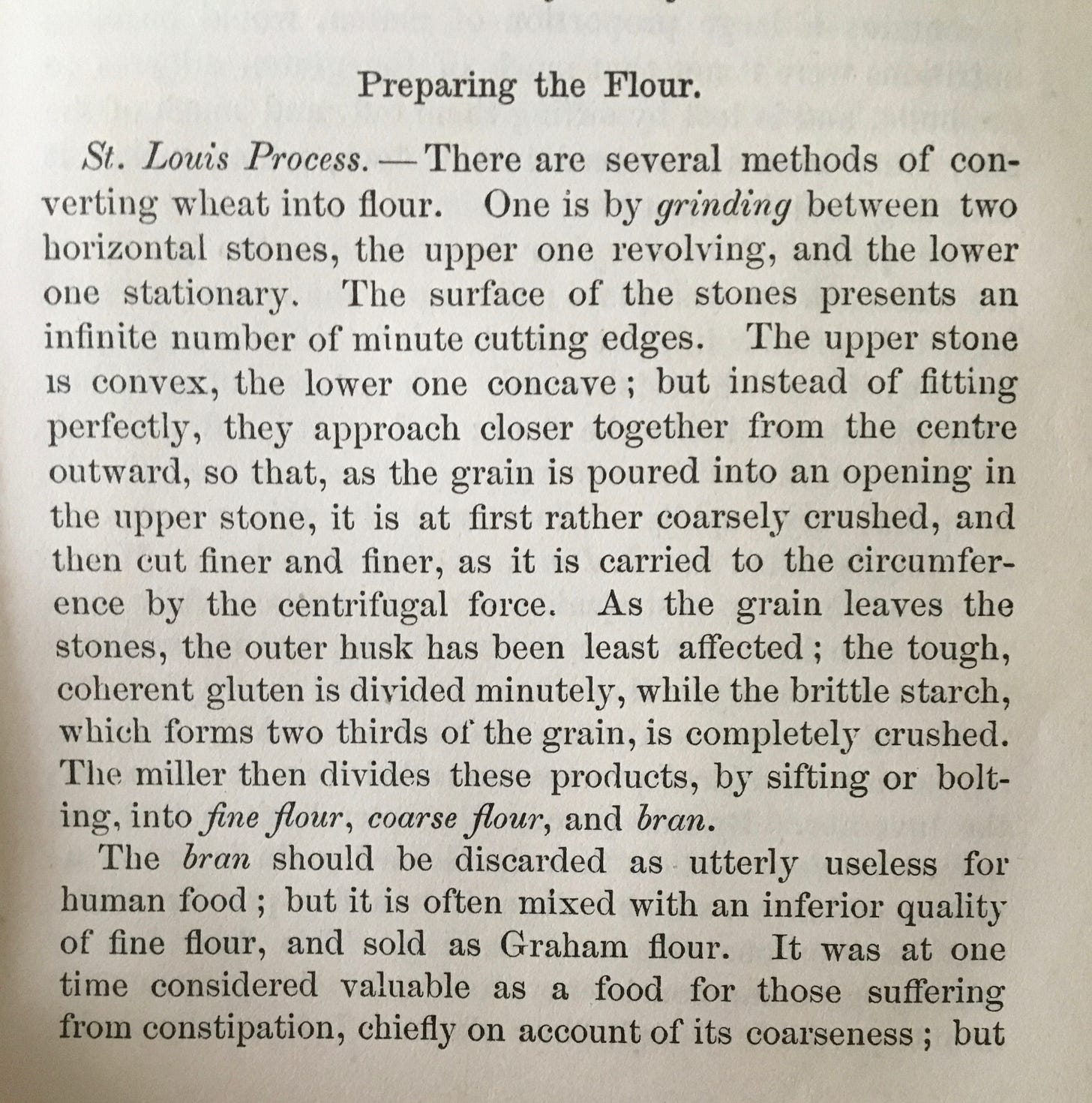

In her cookbook, Mrs. Lincoln goes into great detail about the flour milling processes. Note that low milling is what she calls the St. Louis process - for contemporary context, this is what many of the mills using regional grain use, stone mills from Meadows, New American Stone Mills, Jansen Mills, Engsko or Ostiroller.

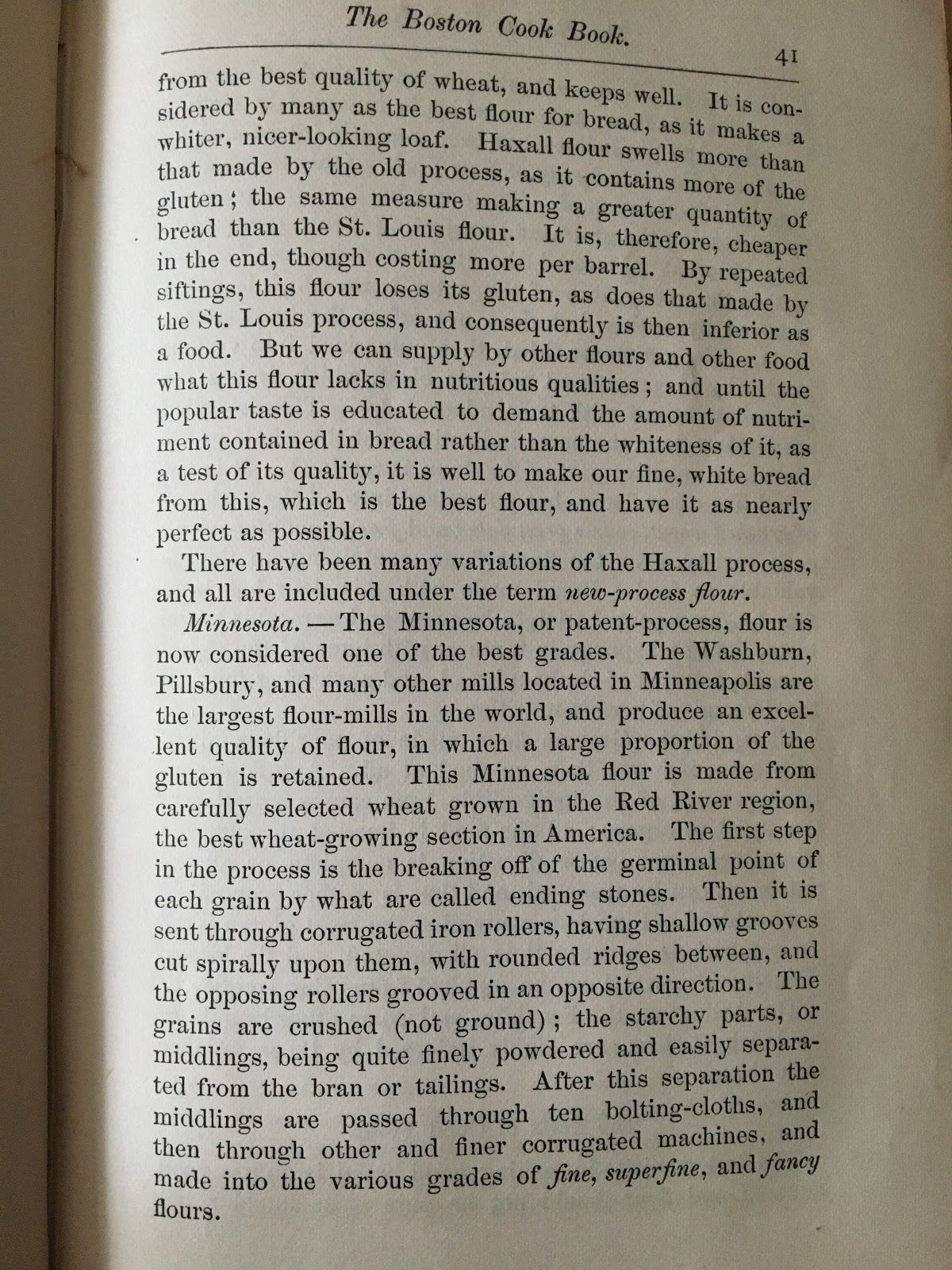

Mrs. Lincoln names the milling processes by place because milling centers moved as the United States pushed westward. (Keep in mind that clearing the slate for developing agriculture and the industrial capacity of different regions meant forced removal of Native Americans from their homelands.)

Mrs. Lincoln’s joy over Minnesota wheat was not unique — it was a wonder to many. The winters were too cold for the fall planted wheat that was common elsewhere, and this spring planted wheat had high protein, which was terrific for bread. Minneapolis millers took advantage of new technologies, and this was the first region to adopt roller mills and purifiers, innovations that made for the flour Mrs. Lincoln praises.

Roller mills were invented in Hungary and Austria in the 1840s, and only came to America in the 1870s, and the success of Minneapolis or Minnesota flour is attributed to the millers embracing change. The water power of St. Anthony Falls was also a factor, as was the coordinated effort to really build an industry, from farm to flour. One of the great historical snapshots of a state and its wheat is this article, King Wheat. Even if you don’t want to know about Minnesota in particular, I think you’ll like to learn about what wheat meant to people and places, before it became just a symbol in a song.

The Haxall process is something I never read of until this book, though I had heard of the first part of the process. Removing the outer layers of bran from grain kernels prior to milling is frequently used in roller milling. And the Haxall process seems like a hammer mill, an impact mill made of metal hammers rotating in a chamber to pound kernels.

Hammer mills are used by some contemporary small mills, though they are not as common as stone mills. Roller mills are used by a few mills, such as Cairnspring Mill, Hillside Grain, and Le Moulin des Cèdres. The latter is in Quebec, and was made in the 1940s in France. The first two mills are modern models of half-high or new process milling, incorporating stone and roller mills to get the best of all worlds.

One important thing to consider when trying to wrap your head around this fresh flour category is scale. Contemporary regional milling is better described as micro- or even nano-milling than small-scale. The mills that make the majority of flour in America are run by four companies around the country, and the daily milling capacity at any one of those macro-mills is sometimes equivalent to what a micro-mill does annually. This fact, the sheer volume of grain that runs through these operations, goes a long way toward explaining the fancy prices that farms and mills working in miniature need to charge. Crop insurance and federal subsidies can explain the low cost of supermarket flour, too, but that’s another story. The scale can help convey the uniformity of widely available flours, too, because they are made from figurative seas of wheat, blended to precision and predictability. No wonder Mrs. Lincoln gives two pages to “The Tests of Good Flour.” There was a lot of stuff to know!

“Good flour should not be pure white in color, but of a creamy, yellowish-white shade. If it feel damp, clammy, or sticky, and gradually form into lumps or cakes, it is not the best. Good flour holds together in a mass, when squeezed by the hand and retains the impression of the fingers, and even the marks of the skin, much longer than poor flour; when made into a dough it is elastic, easy to be kneaded, will stay in a round puffy shape, and will take up a large amount of water: while poor flour will be sticky, flattened, or spread itself over the board, and will never seem to be stiff enough to be handled, no matter how much flour is used...It is extravagant to buy poor or even doubtful flour. But, it should have every appearance of being good flour, and yet not make good bread, do not condemn the flour without a fair trial; and be sure the fault is nowhere else.” — from Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book

That warning, to be sure the fault is nowhere else, refers to the many other pitfalls that a loaf of bread might find on the way to being made. The rest of the chapter on baking bread shows how to avoid such pitfalls, so none of this was any easy. Can you imagine having the skills to assess flour as described? I can’t.

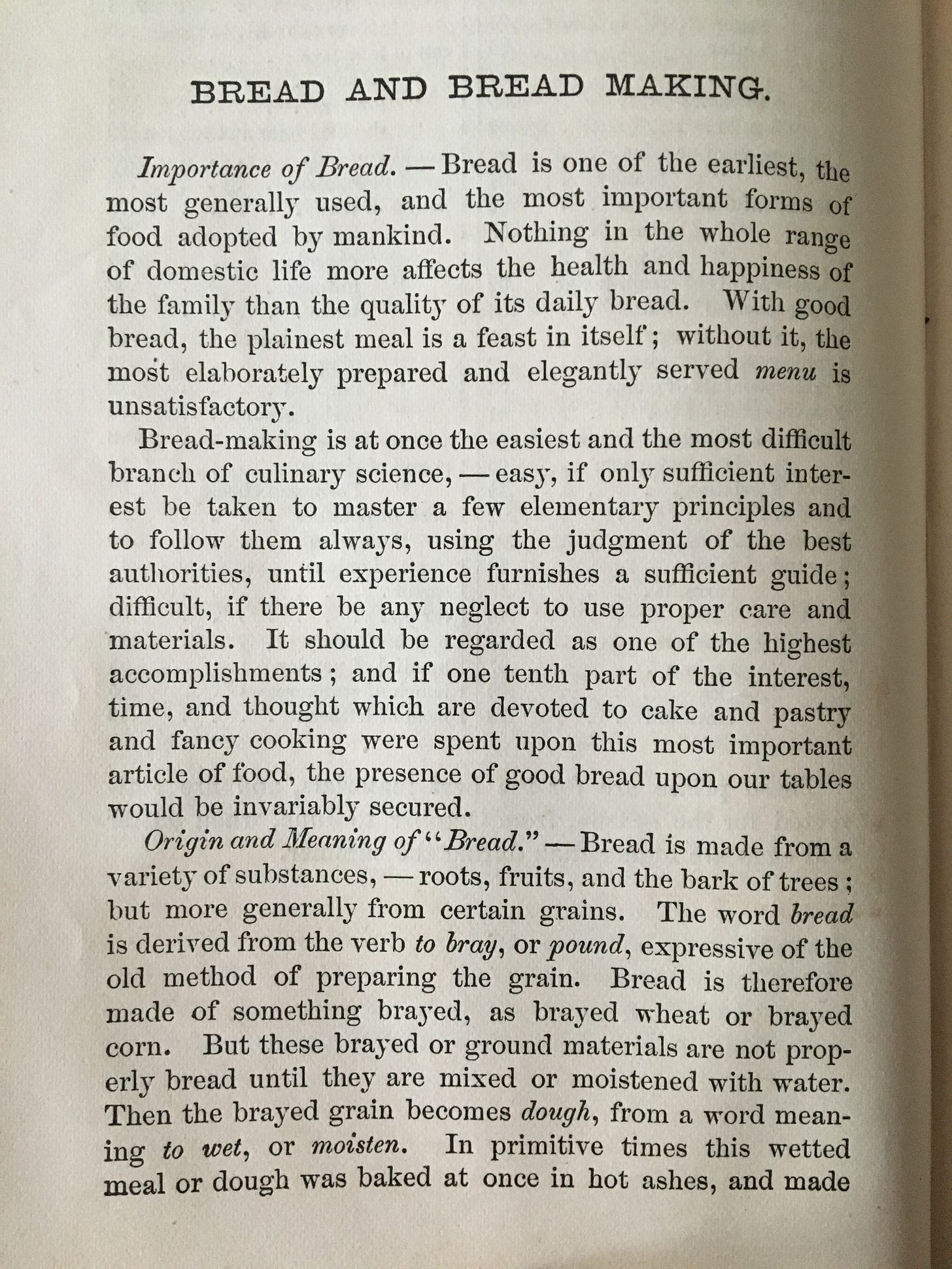

Mrs. Lincoln’s words on bread and bread making are really worth sharing, too.

Apart from what these writers say about flour, I’m intrigued by their connections to the Boston Cooking School. Stay tuned for another bread letter about that.

In the meantime, take care and bake care, Amy