Bread Crumbs

Who is chasing who?

Dear bread, how come you are my compass?

When I was little, I never would have guessed that the hand I would hold most is yours. Did you look down from bread heaven, and say hey, there’s someone who will puzzle over me? Because I do puzzle over you, dear bread, and the way you shine like an everyday diamond, simple as the sun.

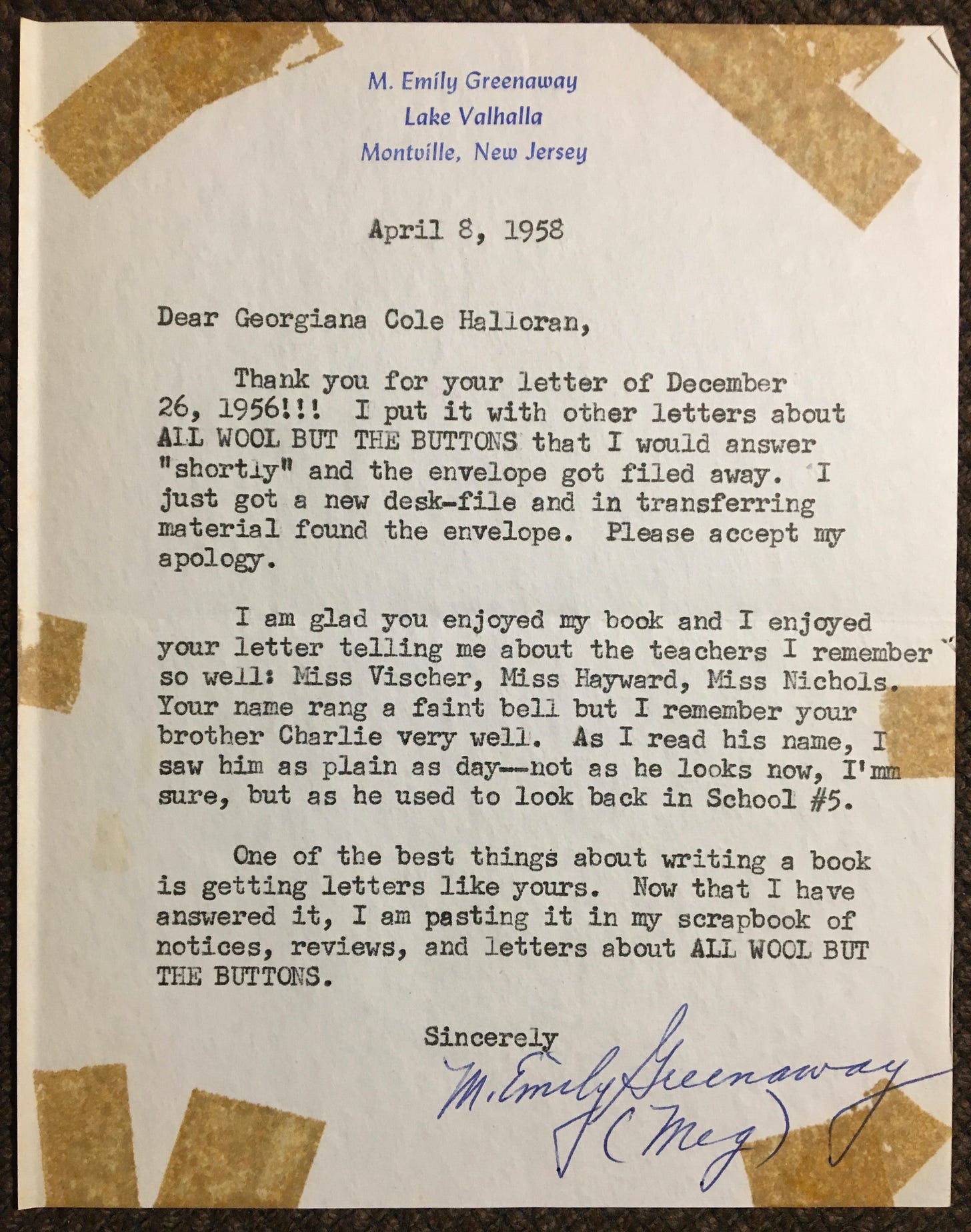

Bread feeds me crumbs, like it is lost, or I am lost and we need to find our way home. The latest crumb is a book I grabbed from my shelf, “All Wool But the Buttons,” by M. Emily Greenaway. On the inside cover, my grandmother, Georgiana Cole Halloran, taped a letter the author wrote her.

"I am glad you enjoyed my book and I enjoyed your letter telling me about the teachers I remember so well...Your name rang a faint bell but I remember your brother Charlie very well. As I read his name I saw him as plain as day -- not as he looks now, I'm sure, but as he used to look back in School #5."

Charlie Cole was born in 1900 and Meg (the author’s nickname, which she used in her signature) was born in 1899. My grandmother was born in 1902. The subtitle of the book is Memories of Life in Upstate New York. While not my family’s memories, they came from the same neighborhood in Cohoes. My excitement climbed when, on the second page of the book, I read that Mr. Greenaway, the author’s father, was a baker. You see why it feels like bread is chasing me?

My grandmother’s sister, Juliette, and her husband-to-be/baker-to-be, George Marcil, were born in 1894, five years sooner than Meg. I don’t know if my great aunt and uncle knew each other as kids, but I do know that George’s father told him to go to a bakery and do anything the owner would let him; working in the mills wouldn’t build skills and opportunities.

Meg Greenaway’s father, however, was born a baker’s son. “The Greenaway men never worked in other men’s shops after they once finished their apprenticeships,” Meg wrote. Yet her dad was a poor businessman and gave bread and treats to anyone who needed them. As he faced bankruptcy, he was “haunted by a long line of white-capped, white-aproned Greenaway bakers, all standing in front of their own shops staring reproachfully at him.”

The sheriff took the shop, which was in Massachusetts, and the family returned to Cohoes, where he’d grown up. Meg’s father worked at a bakery that belonged to someone else, and was generally unhappy; the first chapter is about how she’s hungry for her father’s attention. One way she chased it was going to the bakery to watch him working.

“I liked to see him in his white overalls and apron, his big white hat cocked on the back of his head, and to listen to him whistle as he kneaded the dough. It pleased me to hear the other bakers say, “what do you want me to do next, Bill?” and to have Dad tell them. He never talked to me much, but after a while he told Mom that as long as I seemed to want to walk way down there, I might just as well be carrying his dinner pail.”

Meg liked to clean his “heavy, dough-caked shoes,” but there are not many other pages describing the bakery. The book is mostly about her mother, who could never stick to a schedule for chores, and did the laundry and ironing when there was no other choice. Mrs. Greenaway enjoyed going to the movies, and was glad to take one of her daughter’s out of school to accompany her. The family was NOT Catholic, and her mother was whimsical about which church to attend. In this way, my family really differed. Two of my grandmother’s sisters became nuns.

Scouting in the city directories, I found where the Greenaway’s, Cole’s and Marcil’s lived near the turn of the century. Meg fondly recalls a house on Bevan Street that backed onto woods and a farm, and wouldn’t you know it, my grandmother lived in that house in 1912. It is still standing, so I went and saw it today.

I’m enchanted by houses, as if they’re gift boxes that still hold dead people’s lives. I know this is not true, but the myth grips me. One of my biggest heartbreaks when we bought our home was that I couldn’t connect with the former residents. I didn’t feel ghosts! We shared walls, but nothing else.

So to see a place where Meg Greenaway and her family lived, and where Georgie, Charlie, Juliette, Helen, Mary and Jane lived with their parents, John and Catherine (Lewis) Cole, gave me a bounce. There’s no farm next to the housey-house, a two-story place with a peaked roof. I think it is a single family structure, but it could have had two small apartments. I believe it has the same front doors — heavy wooden things, with coffered panels — that my ten-year-old grandmother would have opened. That Meg’s mother raced to when she was late to make dinner for her husband, having been waylaid by the movies.

This whimsical mother had already had a long career in the Harmony Mills by her late teens; the fibers stuck in her lungs, and she had to quit. “All Wool But the Buttons” is a series of breezy recollections dotted with some cautionary tales about men drinking. The last section of the book is out of character, a grim depiction of an accident Meg’s father had with an automated mixer.

The Greenaway’s moved to Lansingburgh in 1912, and Wm. Greenaway is listed as a baker, but that and other listings don’t indicate where he worked. This is odd. Most people in directories are identified by their residences and places of employment. Women who worked at home didn’t make the books. I’m not sure when child laborers were old enough to be recorded.

Perhaps Mr. Will Greenaway worked at the new factory bakery, Freihofer’s — and the business was too big to be listed? I have to investigate with my local historian. Also, I’m going to see if I can find M. Emily Greenaway’s papers, and see if she wrote more about her family.

I have so many more questions to ask the past. When the book was published, my grandmother was working as a secretary. She was an avid writer of letters to the editor, and nostalgic stories for women’s magazines. She authored my father’s college application, and his teaching job applications too. Was she jealous of this book? Did her letter to M. Emily Greenaway show some mean spiritedness? Or did she accept her situation gracefully?

I will likely never know.

Yours in bread-n-butter,

Amy

William Greenaway was my great grandfather. M. Emily Greenaway was a great aunt of mine. We used to visit her and her partner in Lake Valhalla and Bailey Island Maine where they owned a summer house on a hill near Lands End. Last year a cousin sent me a couple of his recipes.

Whenever I visited Albany to see my grandmother, I always watched Freihofer's "Breadtime Stories". After "We love your cookies, your breads and your cakes" my Uncle would sing "Freddy Freihofer, go jump in the lake"...