Dear Bread people,

I spend my Saturdays baking bread. I like to believe that I’m echoing traditions of women in my city of Troy, New York. I try to imagine the process of handling a week’s worth of bread dough at different eras. The flour, the stoves, the pans, the bowls or wooden troughs. But the more I look at history, the more I see of my reluctance to believe facts and the power of my emotions.

I grew up close to the first factory bakery in my city, Freihofer’s. The first whiff of the power of my feelings is the thought that I lived close enough to smell the bread baking, but we were separated by 25 city blocks!

Many of you will recognize Freihofer’s, a household name in more than upstate New York, most famous now for its chocolate chip cookies, which are available around in many places. Initially, however, bread was its only product, and the company is known here for home delivery, often by horse-drawn wagons. Home delivery continued until 1972, a feat that is hard to imagine given the ubiquity of supermarkets by that time.

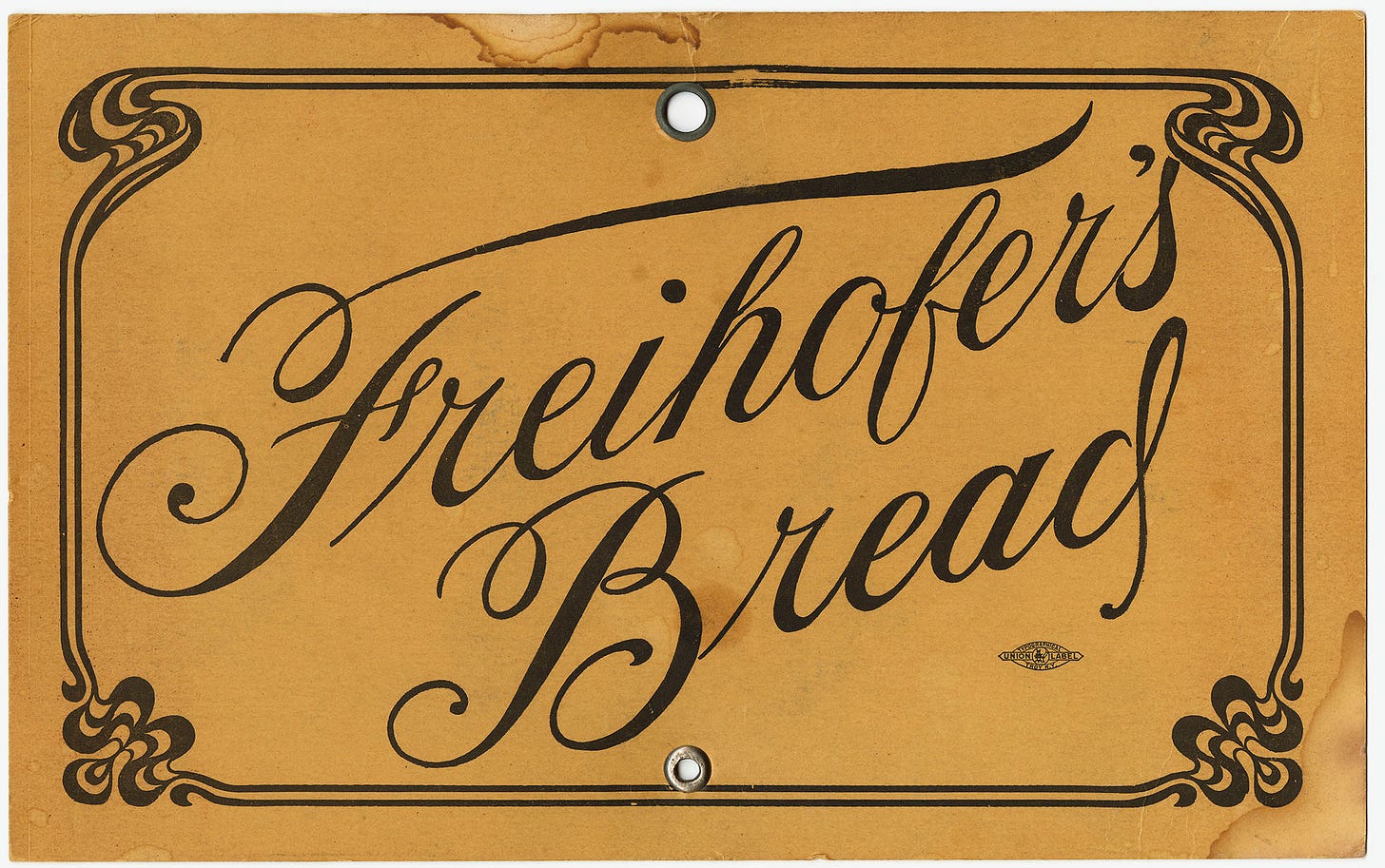

Window sign circa 1945-9 from the Albany Institute of History and Art.

My great aunt told a story of sitting on a streetcar in 1913, and overhearing two men say to one another, “I give Freihofer’s six months.” Thirty years later, my parents watched their parents put one of Freihofer’s placards in the front window, which invited the driver to stop and offer breads. The wagons came around twice a day with freshly baked bread, and in the afternoon the wagons--and eventually, vans--also carried pies and cakes. People have fond memories of feeding Freihofer’s’ horses carrots and apples, and even of scooping up horse manure for their backyard gardens. Others remember the Freddy Freihofer kids’ show on early TV. It was called BreadTime Stories, and while I came along after it went off the air, I learned its theme song from listening to my uncles sing the jingle. “We love your cookies, your bread and your cakes. We love everything Freddy Freihofer makes,” they sing, their eyes twinkling with easy transit to childhood.

Eventually, the bakery was absorbed by national and then international corporations, but the business is firmly rooted in my questions about bread, because it informs my understanding of the city. Freihofer’s story is one of Troy’s origin stories.

Legend and facts have it that Philadelphia bakers Charles and William Freihofer, brothers and business partners, passed through Troy on their way to Montréal in 1911 to purchase a traveling oven. Contrary to their name, these brick ovens didn’t go anywhere. Rather, the bread traveled a long trip through its heated tunnel and came out baked at the other end. Pausing in Troy, Charles Freihofer looked at the Collar City, full of factories with women working in them, and saw his new customer base: women who didn’t have time to bake their own bread. I can't talk about these women without talking about the work they did, so please allow me a little detour into the history of garment manufacturing in Troy.

The women of Collar City were employed in the many factories that made, washed, starched, and ironed shirt collars and cuffs. The removable collar was invented here by Hannah Lord Montague, who was frustrated with her fastidious husband. He wanted a fresh shirt three times a day! Rather than boil water, scrub, dry and iron an entire shirt, she snipped off a collar and, in 1827, created an industry that partially built my city – the iron industry built Troy, too. In the days prior to mechanized washing machines, detachable collars and cuffs became a global habit, and most of them were made in Troy. By the early 1900s, Troy also boasted a booming shirt business. The Cluett & Peabody company and their Arrow brand shirts, as well as sanforization, one of the earliest permanent press treatments for fabric, are Trojan also. Charles Freihofer had three sons and wanted to start them in business. Troy would be the spot.

These were the early days of factory bread. An ad published the Bakers Review, a trade journal, in 1917 stated that 70% of bread was homemade, naming the figure to frame the battle the professional baker had to wage. But for urban women in the paid workforce, the battle was already won. The women Charles Freihofer targeted worked six days a week for 10 to 12 hours each day. They weren’t coming home and baking their own bread. But, romantically, I want to believe that they were.

As I make my own sourdough bread, I fantasize that I am living a local history, my hands doing the work of my predecessors. But I know that modern sourdough doesn’t reflect the baking habits of a hundred+ years ago. American cookbooks from the 1800s have recipes for making yeast at home, but nothing that looks like the feeding and maintenance schedules for starters that are popular now.

Baking powder was patented in 1856, and commercial yeast was invented in 1870; both were revolutionary. People have been pursuing shortcuts to coaxing bread from flour for centuries, and we should probably ditch bread nostalgia like a used tissue. Yet the act of baking bread is so satisfying, and was even before it became a balm to the pandemic, and being on the cliff of economic and political chaos, and in the midst of a necessary racial reckoning. Given these challenges, baking--and even imagining we are baking traditionally--makes the past seem more alluring than ever.

I am especially susceptible. I've always been in love with the olden days. This probably comes from growing up in the 1970s, as America whipped itself into a patriotic frenzy over the bicentennial celebration of the revolution. I also had an incredible hunger for connecting with people, living and dead. Most of my grandparents died when I was young and I dreamt of meeting them one day in heaven, which I pictured as a graveyard in the clouds. My father's mother, I was sure, would have made the acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln. I looked forward to meeting him.

So of course I’ve been revisiting Troy’s past through bread. I wanted to find Freihofer’s recipes, to see if their early factory bread recipes differed much from cookbook recipes of the era. I couldn't find Freihofer’s archives, but thanks to Don Lindgren of Rabelais Books in Maine, I did locate the Tolley Baking Records at the New York Public Library. I got to visit them in February, right before the world closed. I spent a day studying the collection, taking pictures of recipes written with fountain pens and scratched on envelopes, receipts and other scraps. (Oh how I loved seeing the tiny pieces of paper with lists of ingredients! Take notes everyone! And keep them!) I read mimeographed typewritten copies of formula books for chain bakeries across the Northeast. These artifacts are from members of the Tolley family, who baked with and managed bakeries for the Ward Baking Company, Pittsburgh and New York City’s first factory bakery and the eventual monopolistic parent company of Wonder Bread. The notebooks ranged from 1904-1967.

Generally, I recognized the ingredients: flour, water, sugar, molasses, yeast, salt, milk, oil and many kinds of fat, from lard to forgotten Crisco-competitors circa 1910. I discovered that red dog is a kind of low-grade flour, and I did see malt extract used, but there were no additives or dough conditioners. These suspects entered later, starting in 1924 with Arkady, a mineral salt ‘yeast food’ that sped and controlled fermentation.

A French bread formula dated 1911 listed water, salt, sugar, yeast and spring -- spring being a shorthand reference to flour made from spring planted wheat. This is the closest date and name-wise I came to tracking a recipe that would parallel Freihofer’s bread when it opened on March 12, 1913. The horse-drawn wagons delivered two types, Pan Bread and French Bread, free to people all over the city. In the days that followed, they ran ads in the newspaper asking people to tell them if they didn’t get their free bread.

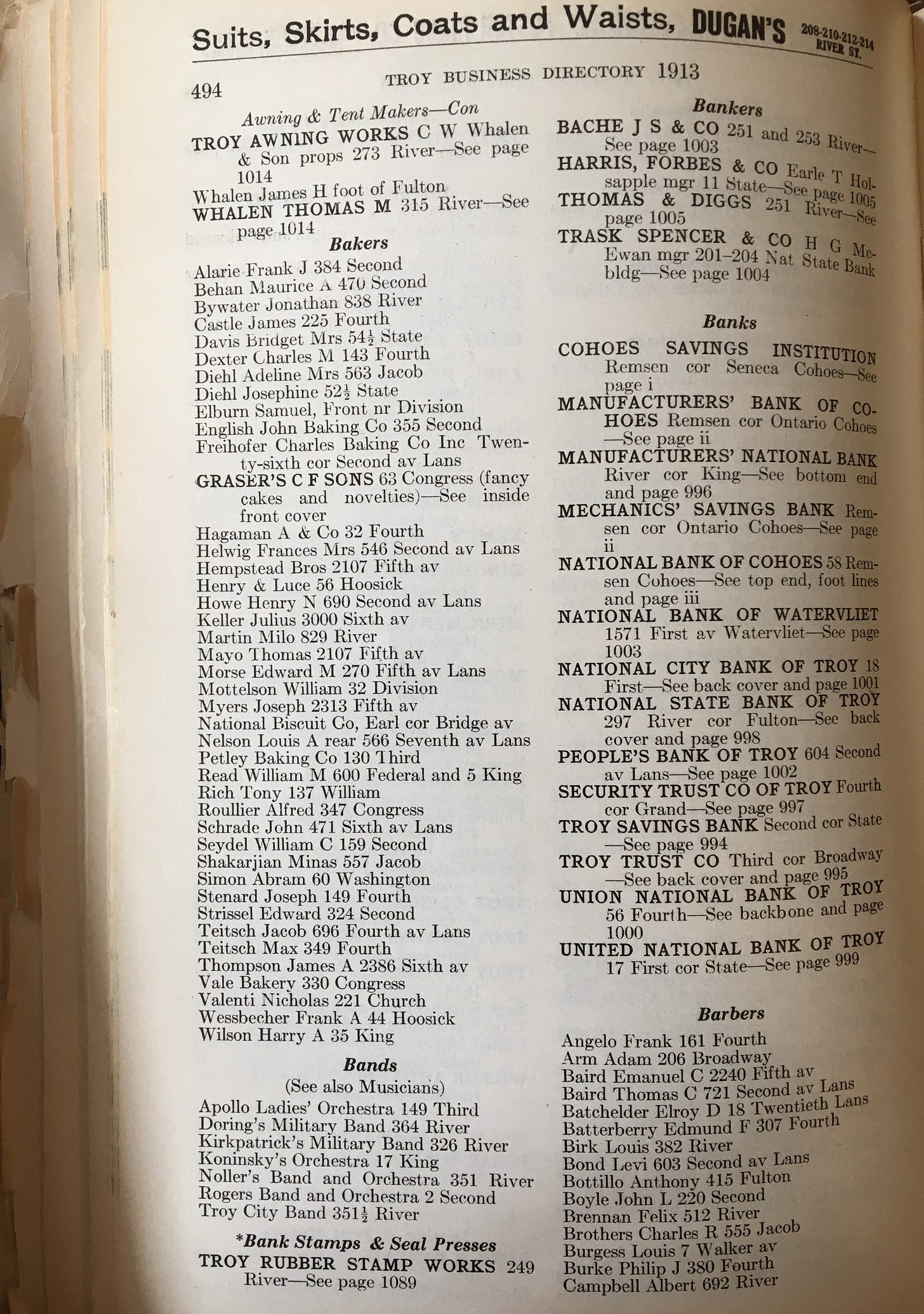

The 1913 City Directory, photographed at the Troy Public Library.

I can't ask the past how many loaves Freihofer's gave away in their opening days, but I can look at the city directories to assess the business landscape. City directories list working residents and businesses, and in 1910 there were 43 bakeries in Troy; the population was 76,910. In 1913, with Freihofer's added to that list, there were 42 bakeries; five years later, there were only 29 bakeries left. The population had dropped by about 5,000 people from 1910 - 18. Nearby, two other Freihofer bakeries opened in Troy’s neighboring cities, Albany and Schenectady.

I called up the Rensselaer County historian Kathy Sheehan at the Hart Cluett Museum to ask her about Freihofer’s impact and who was making bread at home. She named a 1920-1926 study that looked at jobs in Troy and found that more than 50% of the workforce was women, and many of them were still working up to 12 hours a day.

“Women didn’t bake the bread any more than they churned the butter!” Kathy laughed, and I suddenly realized the ridiculousness of my question. I was living in a false shadow, wanting urban working women of the late 19th and early 20th century to conform to my notions of hearth and self. These women’s realities weren't the mental picture I constructed for them. They lived in cramped apartments, and, depending on the time period, probably brought baked potatoes to work, cooked overnight in the banked coals of their wood/coal stoves. But anytime between 1860-1915, the heydays of the collar and cuff industry, these workers were not DIYing their staples. Bread baking, and more specifically leavened wheat bread, was a food habit that young women most likely left at the farm, as they migrated from subsistence farmsteads in New England or from abroad to work in mills and factories.

My imaginary women of Troy bought bread from one of the many small bakeries that dotted the city. Looking at the lists of bakeries in city directories, I found the names of the bakers who ran a basement bakery in a house my friend owns. Herman Fruh. Joseph Schrade. Both of them baked through Freihofer’s beginnings, and someone kept running that business into the 1960s. Visiting the brick oven and proofing room which is now my friend’s cellar was spooky and quotidian, eerie and completely normal. I stood next to the oven and visualized the work, wondering what the display cases would have looked like on the first floor.

Freihofer’s didn’t slay all the little bakeries, but what’s it going to take to slay my ideas of women baking at home? I suspect I’ll remain in love with baking, and keep forgetting that I have the luxury of time and an easy-to-heat oven. I’ll keep fighting with myself as I apply my imagination to history, trying to make the past look like what I know, what I love.

Why? Because time is so slippery and hard to hold. We are in it but it is intangible. That moment passed? And that one! Now this one? How can we reckon with the accumulation of lives and experiences that are under ours, and with the impossible reality that our own experiences are not stacked under us, but have vanished? My solution is to paste what I know and feel right now onto other eras. Maybe I’ll begin to remember that my bandaid for losing each now is falling into what was, that I’ve got a nostalgic strategy for coping with loss. Maybe I’ll stop trying to look at old methods of bread baking through contemporary lenses. Or maybe I’ll keep on with the rose colored glasses, and accept my romantic tendencies. If you’re game to watch me fumble with feelings and facts, stay tuned for my next letter.

Yours, Amy

Wish I had the original recipe of my family

Congratulations on your new platform. I'll be looking forward to your letters!