Tools

Brown bread, cast iron cook stoves, and other improvements

Dear bread friends,

I have felt an allegiance to baking most of my life. The kitchen is where I am most often, and the tools I use seem like mirrors. I don’t have to be in my parents’ kitchen to still feel their tools in my hands: the round aluminum griddle of my childhood that I used for pancakes, a round, stainless steel bowl with a wide lip that held every batch of cookie dough I made. Only the wooden spoons I used are gone, so I can’t use them when I visit. But I can still remember holding them, the way each one fit in my grip, against my palm.

Tools determine so much of our lives, setting the stage for what we can do easily and where we have to struggle. I learned this over and over again as I ran a soup kitchen and food pantry. I went into the job thinking I could teach people about the importance of vegetables, and I quickly saw that people knew what they should eat. On the cafeteria line, some people didn’t have teeth, the most basic of tools. As I offered cooking classes, I learned that people knew how to cook, but they didn’t have the tools of money or time. As I figured out ways to get more fresh produce in the pantry, I saw that people had to limit what they carried home on the bus, or pushed in their shopping carts. They made logical choices about what they could carry, and a 5-pound bag of potatoes might win over a 3-pound bag of apples, because the apples were extravagant calories, the potatoes practical.

The pantry and dining room were part of a large human service agency, so people didn’t just come for food, but for help getting their utilities turned back on and to avoid getting evicted. They needed furniture and plates and knives and mixing bowls for new apartments because various crises forced them to move frequently, oftentimes leaving previous belongings behind. When I started to notice that grant applications for food projects stated that they wouldn’t fund pots and pans or blenders, or pay for ingredients, I got frustrated. I wanted to do more than feed people, I wanted to nourish them, and that would mean equipping them with big picture stuff, like affordable housing and stable incomes.

I managed a lot of volunteers, and in our time together, I tried to squeeze in stories about the limited toolboxes pantry patrons worked with. Group by group, person by person, I wanted to overcome the othering that divides people with material resources from people with less wealth. I could be a bridge of information, help middle-class people understand some of the barriers created by the socioeconomic limits in America. I gauged each audience, trying to find a story that would hit home. When corporate teams came to volunteer, I might talk about people not having good knives at home as we chopped mountains of broccoli. I might drop a line about how I brought good knives to a vacation house, and how that made me think about trying to cook from a slapdash kitchen every day. Tools. They make us and they unmake us.

Ovens are the tools I’ve been considering lately. I’ve been reading a lot of old cookbooks, and am intrigued by the many recipes that use rye flour and cornmeal. One of these is brown bread, a bread that reflects a time and a place. Paula Marcoux is a cookbook author and historian; this video she made about wood-fired brown bread is a great immersion in its process, one that begs you to make her recipe for Steamed Brown Bread using a kettle on top of your stove. This soft, dense loaf is more like cake than anything else. I have special pans to make it that came from my husband’s family, but clever cooks of the day reused metal lard pails that were made with a well-fitted cover specifically for this purpose.

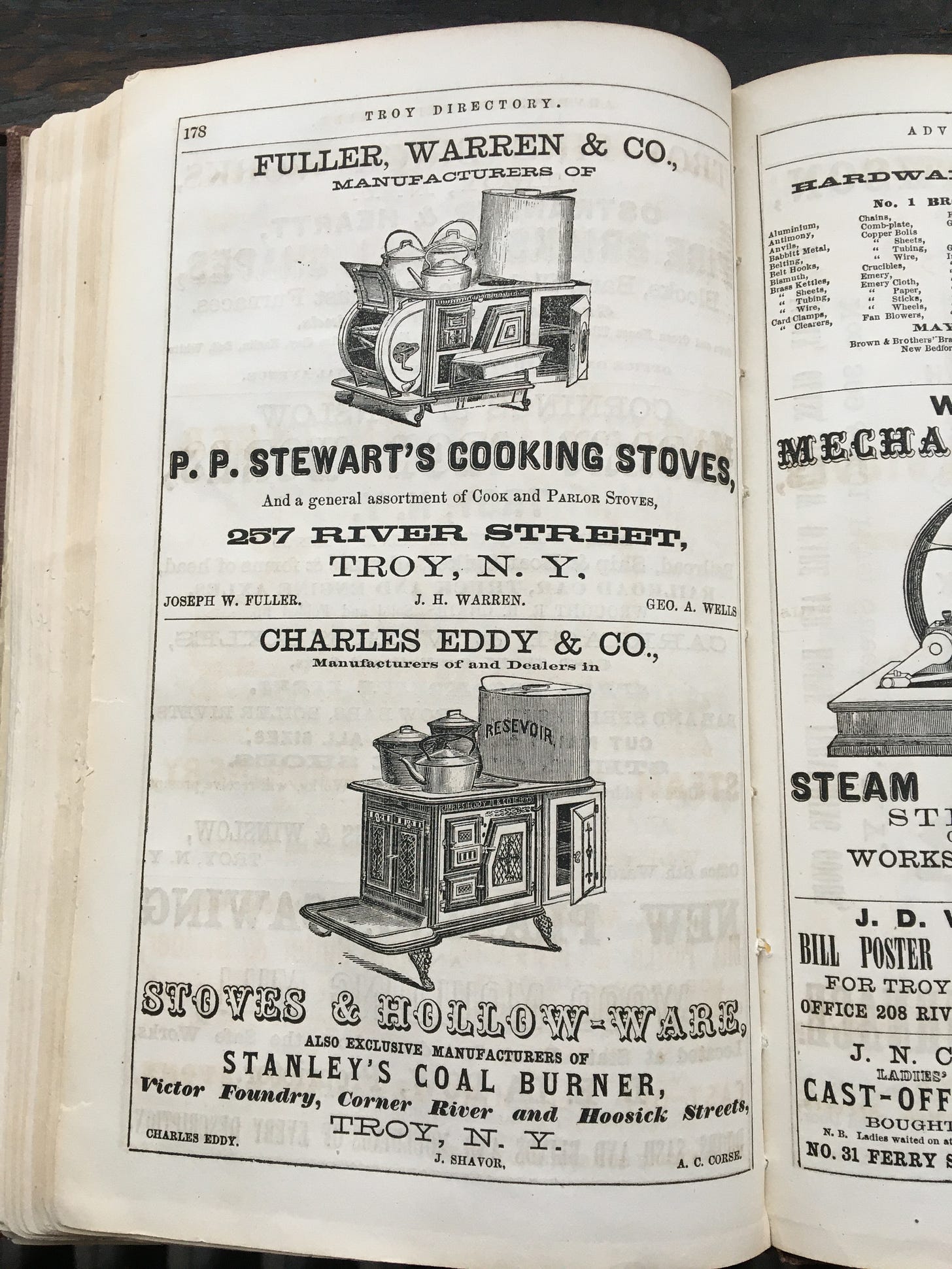

In her book Cooking with Fire, Marcoux shows how cooks adapted to cast iron cook stoves, which took over American kitchens in the nineteenth century, by steaming bread rather than baking it. These ovens were more difficult to use than the dependable brick ovens that bakers had been long accustomed to, and the ranges excelled at steady boiling, providing as much hot water and steam as a cook could desire, all day long, and on a conveniently waist-high and perfectly flat surface.

The poor baking quality of these stoves also led to lots of innovations, many of which happened near me. Though I’ve never studied the iron industry, I can’t avoid knowing the basics of such a foundational economy. The massive waterwheel for Burden Iron Works inspired the Ferris Wheel, and Troy made horseshoes for the Union Army and ironsides for a ship pivotal in the Civil War. Looking into stoves, I discovered an unpublished book on the internet, A Nation of Stoves, by historian Howell Harris. A few chapters helped me learn about how Albany, which is across the Hudson River, and Troy became hotbeds of stove-making and improvements starting in the early 1800s.

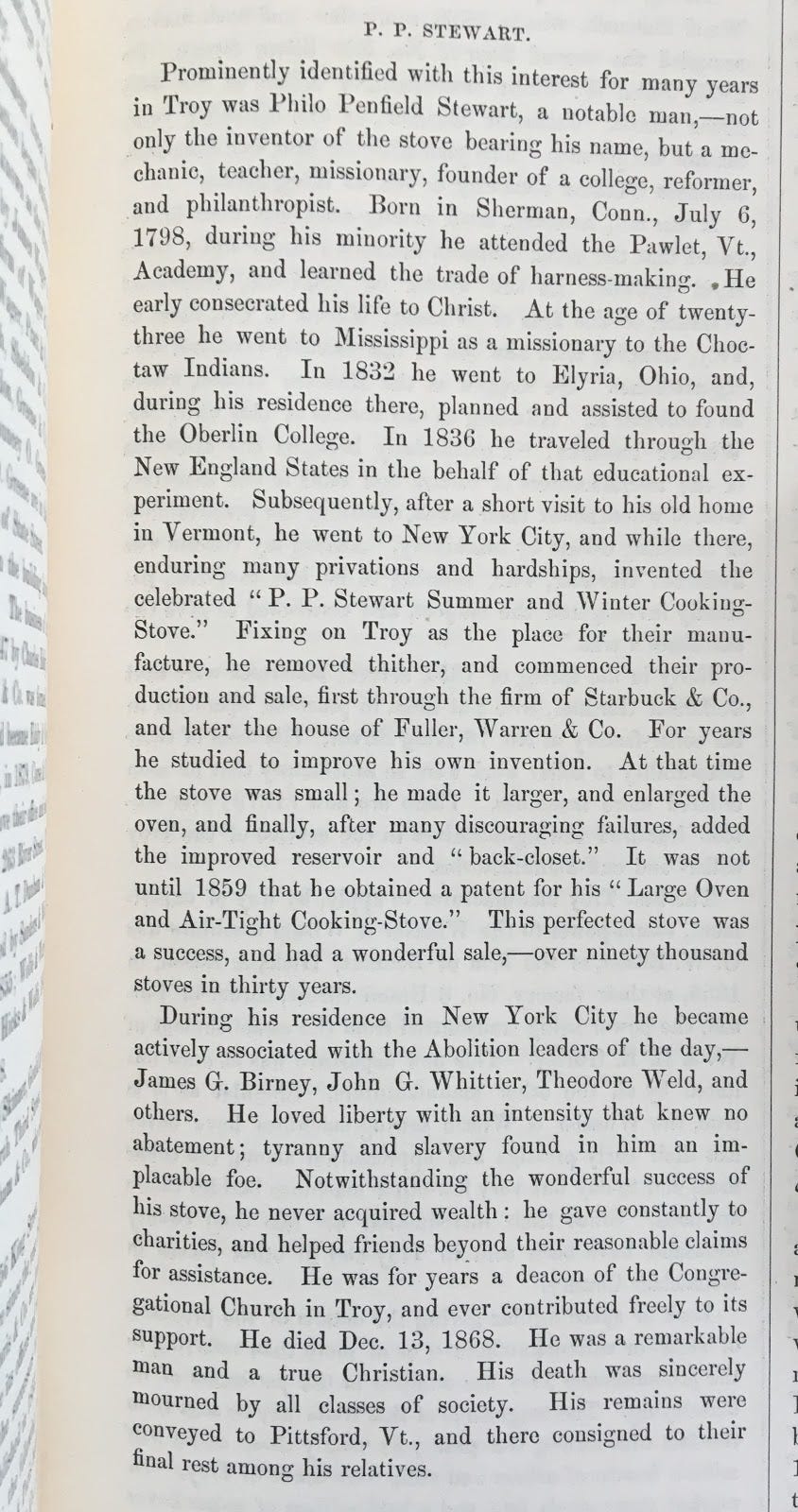

Harris wrote an extensive profile of Philo P. Stewart, whose name became the Kleenex of good cookstoves. Harris’s writing and research are so thorough, and so good, that I encourage you to read what he’s written. His source lists have sent me into lots of reading and conversations to try to understand this man and how he landed in my city. This all helped me consider the idea of tools both in the abstract and in concrete terms, as physical things that help us.

Stewart was a missionary and reformer born in 1798 in Connecticut. His father died when he was ten, so he moved to Vermont to live with his grandfather, who was a miller. Within a few years he was apprenticed to his uncle, a saddle and harness maker; during this period he also attended the Pawlet Academy, working six hours a day at each task. One of his instructors set him on a religious path, and following his apprenticeship, he had no interest in the trade. When interviewing for a job as a schoolteacher, he was offered grain as his pay rather than money. Initially he turned the job down, but, as his wife Ellen wrote in a posthumous sketch, P.P. Stewart, A Worker, and Workers’ Friend:

“…meditating on 'the situation,' he suddenly made a discovery. He saw very clearly, as if by divine illumination, that his will was not wholly subdued. 'Love of money' was lurking in his heart. He now determined that, God helping, he would put away everything that threatened to impede his Christian usefulness. In his solitary journeying he held converse with himself after this manner: 'I profess to be a follower of Christ. He was rich, but for my sake he became poor. He went about doing good, and had not anywhere to lay His head. I profess to want to make myself useful among men, and to be willing to deny myself, and to suffer shame for His name. Here, now, is a capital chance to do good, but I refuse it because I am to receive my pay in grain instead of money. This is not Christ-like; I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes; I will accept this opportunity and trust in God. From this time henceforth, I will hold myself and every dollar I possess in readiness to be employed or given up, as duty calls, for Jesus’s sake, as long as I live.” (p 26)

As a person of religious doubt, I don’t understand faith, nor what it makes people do. My background, and the community I’ve kept as an adult, has primed me to feel dubious about people who have a Christian compass. I noticed that when I read that he was a missionary, I felt he would be foreign to me.

When I read that he was an inventor, however, I had a reflex of respect. I know that my impressions of these two categories, missionaries and inventors, come from everything I’ve absorbed. My culture worships heroes, and I grew up with sports heroes on Wheaties boxes and elementary school biographies praising Ben Franklin and Alexander Graham Bell. The concept of individual achievement and inventing were praiseworthy. As I try to make the smallest sense of Philo P. Stewart and his life and writings, I realize that my prejudices sully my impressions.

So, in search of context, I meandered through his wife Ellen’s writings; the history of Oberlin College, which he founded with a friend, and of course the city directories, trying to find as many footprints of him as I could. My favorite hunting ground, the Troy Public Library’s Troy Room, is open, so I made an appointment for a visit. I found the following brief biography in a grand book with gilt lettering: History of Rensselaer Co., New York by Nathaniel Bartlett Sylvester (Everts & Peck, Philadelphia, 1880)

I was excited to study the city directories and see where he lived. (If you don’t know these gems yet, think phone books before phones existed, and with people’s jobs listed aside their names and addresses.) Would I know the building? Might I have been inside it? Could I stand outside it now? Knock on a door and explain why I wanted to be in a stranger’s house during a pandemic?

My heart raced as I read that he and Ellen lived near a block where I spent a lot of time as a teenager, in love with vacant buildings and courting ghosts. The house numbers were unfamiliar though, so I had to ask historian Kathy Sheehan for help. Turns out that the Stewart’s house burned in the 1862 fire that consumed much of downtown. They called their home The United States Hotel, and had an open door for missionaries and worn-out ministers; they also invited paying guests to take a water cure, a retreat from the many physical and nervous stressors of being alive in the mid-1800s. The Stewart’s based their methods on how they’d cured themselves of many ailments, and incorporated strict diets, exercise (If you want to try his workout, look here), bathing, and other hydrotherapy routines. Their residence was also a stop on the Underground Railroad, and the pall bearers at Philo’s funeral were “colored” men.

Philo and Ellen Stewart were incredibly philanthropic. They didn’t dedicate themselves to the glory of stove-making for glory’s sake, but for the useful improvements they could offer other people’s lives by having a more economical and functional cookstove. They earned money to give it away, living very frugally in order to give as much as possible, steering away from those luxuries of coffee, tea, butter and meat their whole lives. Salt seemed an extravagance, too. Their earnings and savings went to Oberlin and many other causes.

I was raised to be helpful, but not self-sacrificing (except during Lent), and the Stewart’s fascinate me with their commitment to thrift and helping. Seems like they saw their lives as gifts that they could give in the name of community.

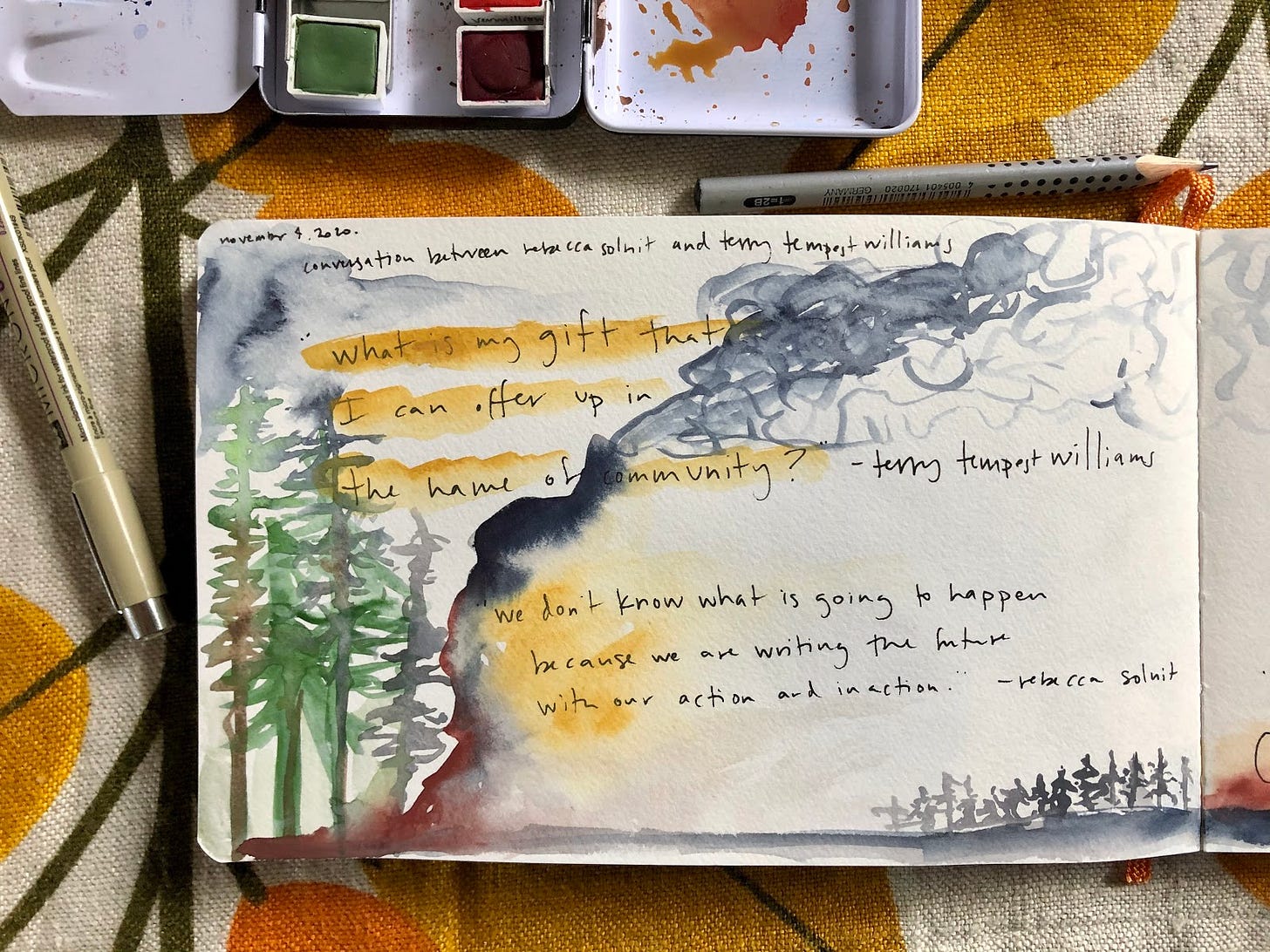

I’m borrowing language here, from Anna Brones, a paper cut artist and art activist I admire. After the election, in her Creative Fuel newsletter, she got me thinking about gifts and tools.

“We must identify our gift that we will offer in the name of community. Is it writing? Is it art? Is it conversation? Is it advocacy? Is it protesting? Is it listening? Is it educating? Whatever it is, there is work to be done,” she wrote, synthesizing thoughts from a conversation between Terry Tempest Williams and Rebecca Solnit.

I am still wondering what my real tools are, and how to use my gifts. So I offer you her questions, because we really need to be useful to each other. The prejudices exposed by the election are raw and frightening, especially for the many groups of people vulnerable to white supremacy and gender norms.

There is no simple bridge between the 70+ million who voted for Trump and the 74+ million who voted for Biden. What we have to do is find our tools, whether it’s perfecting cookstoves, working at mass food distributions, baking against racism or bringing your neighbor a birthday cake, or any of the many, many more examples that are yours to identify. Time to grab your tools and get to work.

Yours, Amy

What a beautiful essay, Amy! Thank you, Rita