Hello Dear Reader,

This summer I’m going to explore my neighborhood, and a handful of women.

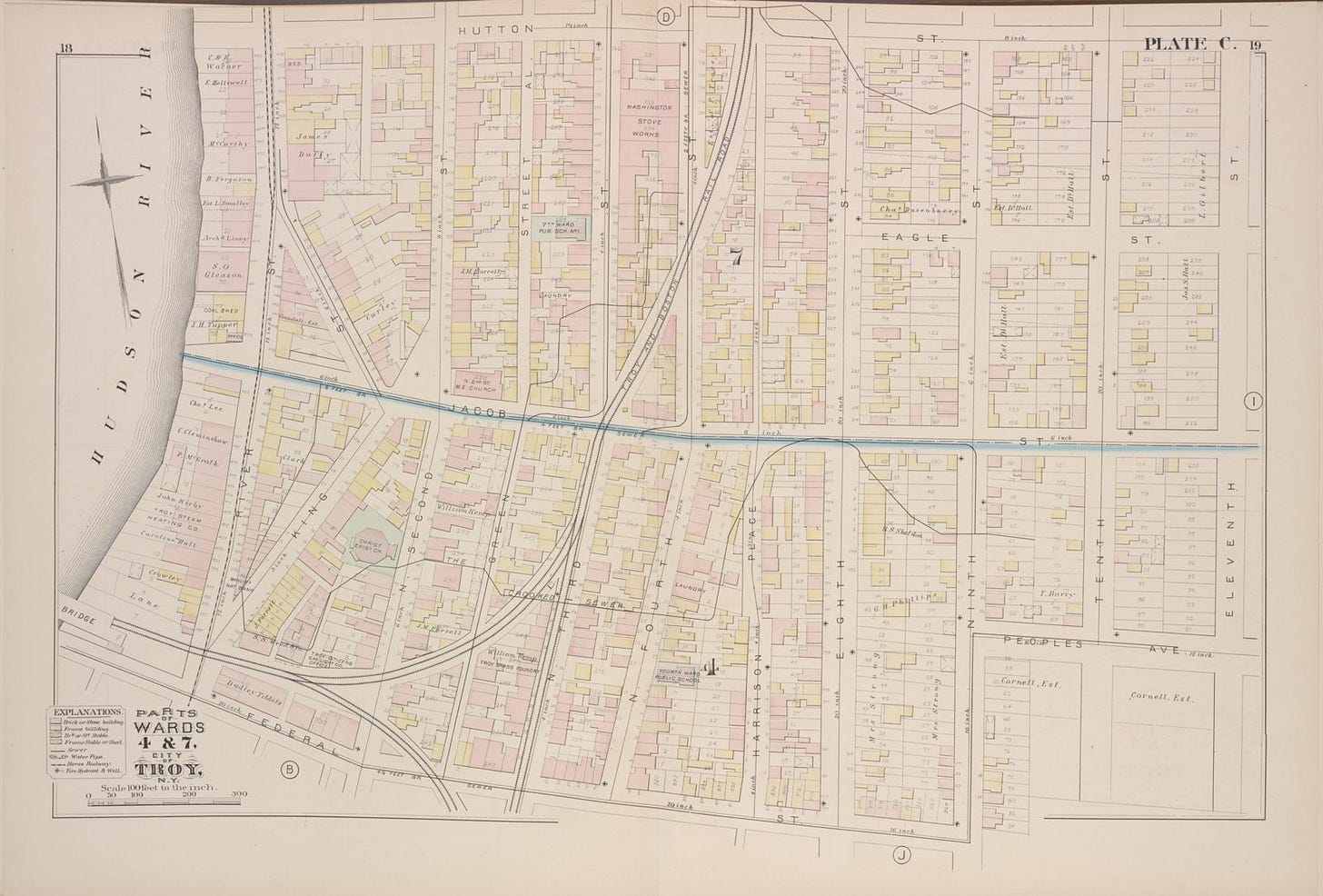

I moved home to upstate New York 24 years ago. As I settled in, I wanted to know how residents shaped my city, Troy, New York. Did they have a voice during its urban renewal/removal period? Did the slap of the 8-lane bridge come at the people’s bidding? Was the dead mall downtown once desired? Now, I’m asking similar questions about relatives. How did they get to be?

This happened because of bread, of course! Wondering how bread became the supermarket sandwich loaves I ate growing up, I studied breads of the early 20th century, and discovered real people I’m sewn to, professional bakers George Marcil and Will Greenaway. I am linked to these men by a few women:

Minnie Emily Greenaway, a writer I’ve come to think of as a mentor. Her father worked in small bakeries, and I loved what she wrote about him and his thoughts about mixers. He did not like them! Thought they beat all the flavor out of bread. The Greenaway’s lived in a house behind mine in 1924.

My great aunt Juliette Cole Marcil, who married George. They lived above Marcil Brothers Bakery in Cohoes through the 1920s, until the business closed in the Great Depression. Then, they moved to my neighborhood.

My great aunt, Sister Dorothea, born Mary Cole, lived in a convent two blocks uphill from my house.

My family ties to the blocks around me didn’t register until my own kids were grown and nearly fledged. Even as I explored the pedestrian voices of Troy to see what impact they had on the life of the city, my ancestors didn’t seem significant. They weren’t my grandparents, and they were mostly women, people I underestimated because no matter how feminist I was raised, I got the memo that Big Things Are Done by Men. But when Minnie came on my radar, she mattered because her accomplishments — authoring three books — were valuable. Admiring her has made me curious about my blood mentors, too. I’m chagrined that I discounted them!

My questions for these women are the same as what I asked my city in the year 2000. How do people shape the world and how does the world shape us? The massive Hoosick Street Bridge and the monolith of factory bread hit us without a vote. You might say we vote with our forks, but we can only poke our forks in the food that reaches us. We can only travel the roads that we have. This isn’t defeatist. Our choices are set by circumstances.

Minnie has set a fire in me to explore what women of the early 20th century got to be. I want to know what agency this handful of women had. They were all born in the 1890s. My grandmothers were born just a bit later, and I’m going to be looking at them too.

For the past few years, I have been studying their era because of bread. The transition from home baking to factory bread intrigued me, and that’s how I found ties to local bakers. George Marcil’s grandchildren gave me his handwritten recipe book and his professional cookbooks. All Wool But the Buttons, Minnie’s memoir includes stories of Will Greenaway baking, and gave me a baker’s impression of the changing industry. Looking beyond these men, I learned how advertising influenced the rise of factory bread, identifying housewives as bakers’ prime competition. The less time mothers spend kneading, the ads said, the more time mothers have for reading – to children, the copy specified, not for their own edification.

The more I looked at bread, though, the more Minnie called me. Who is she? What did she think about as she looked out her back window a hundred years ago?

When I hang clothes on the line, I imagine her looking at Mrs. Oates, the woman who lived in my house, clipping sheets to dry. Minnie looks at the laundry, and at a woman working, and into her own future. Hanging my own sheets and clothes, I feel her eyes on me, on the future she lived and left. While my laundry dries, and when I’m folding it, and afterwards, again and again, I look back on the past, puzzling over the figurative rocks of the twentieth century to see how she climbed them. She became a high school teacher, and then a college professor, and an author. How did she and my relatives get to be the women they were, living and dying, and everything in between? Who do we get to be?

Minnie, Juliette, Sister Dorothea, and my grandmothers Georgiana Cole Halloran and Eva Zaleska Sweeney: this is my cast of characters. By 1930, these women were adults, and coincidentally, this is when more bread was bought than baked at home. In a sense, these women grew up as bread did.

I suppose I’m looking at how American women and American bread grew up. Visibly. Invisibly. I hope you’ll follow along and invite your friends to join you as I dive into a summer of women and bread.

Yours, Amy

Bread notes:

The war years certainly contributed to Americans accepting factory bread over homemade, and I found a good, brief summary of this at The National WWI Museum and Memorial’s website. I hope you’ll read Aaron Bobrow-Strain’s great book, White Bread: A Social History of the Store Bought Loaf, which covers this terrain.

Here is a film of bread in the 1920s, starting in a bakery and covering harvest.

Fascinating! You are fortunate to have such deep ties to where you live. I don't know much about who lived in our 129-year-old house before us, but like you, I think of the women who lived there before me, particularly when I hang out laundry to dry. I feel that this act connects me to them. I also look forward to following your series.

This is wonderful, Amy, I love how you framed this - they grew up as bread did. Looking forward to following your series. 🍞