Dear Bread Fans,

I’m cleaning my papers, again. Often, I begin by googling for advice, but this time I inadvertently dove in, while gearing up to write about Minnie Greenaway, a writer who fascinates me, and who lived in the house behind mine a hundred years ago.

M. Emily Greenaway — aka Meg or Minnie, was born in 1899 in Cohoes, and her father was a baker. In 1924 she was 25 and a student at the State College in Albany. I bet she was also working, because the previous year she was listed in the city directory as a stenographer.

I want to imagine a day in her life, so I’m studying trolleys, and wondering where her streetcar crossed the Hudson. I’m mapping the grocers in our neighborhood, too — there were 7 within 2 blocks of her house, and her landlord, Bagdassar Bakerian, ran another store 6 blocks downhill. The Greenaway’s lived next to the Armenian Church, which had been built in 1914. Her father worked as a baker, and her sister Alberta worked as a clerk. Her mother Rose wasn’t listed at all in the city directory — but that doesn’t mean she didn’t live with them, just that she didn’t have a paid job.

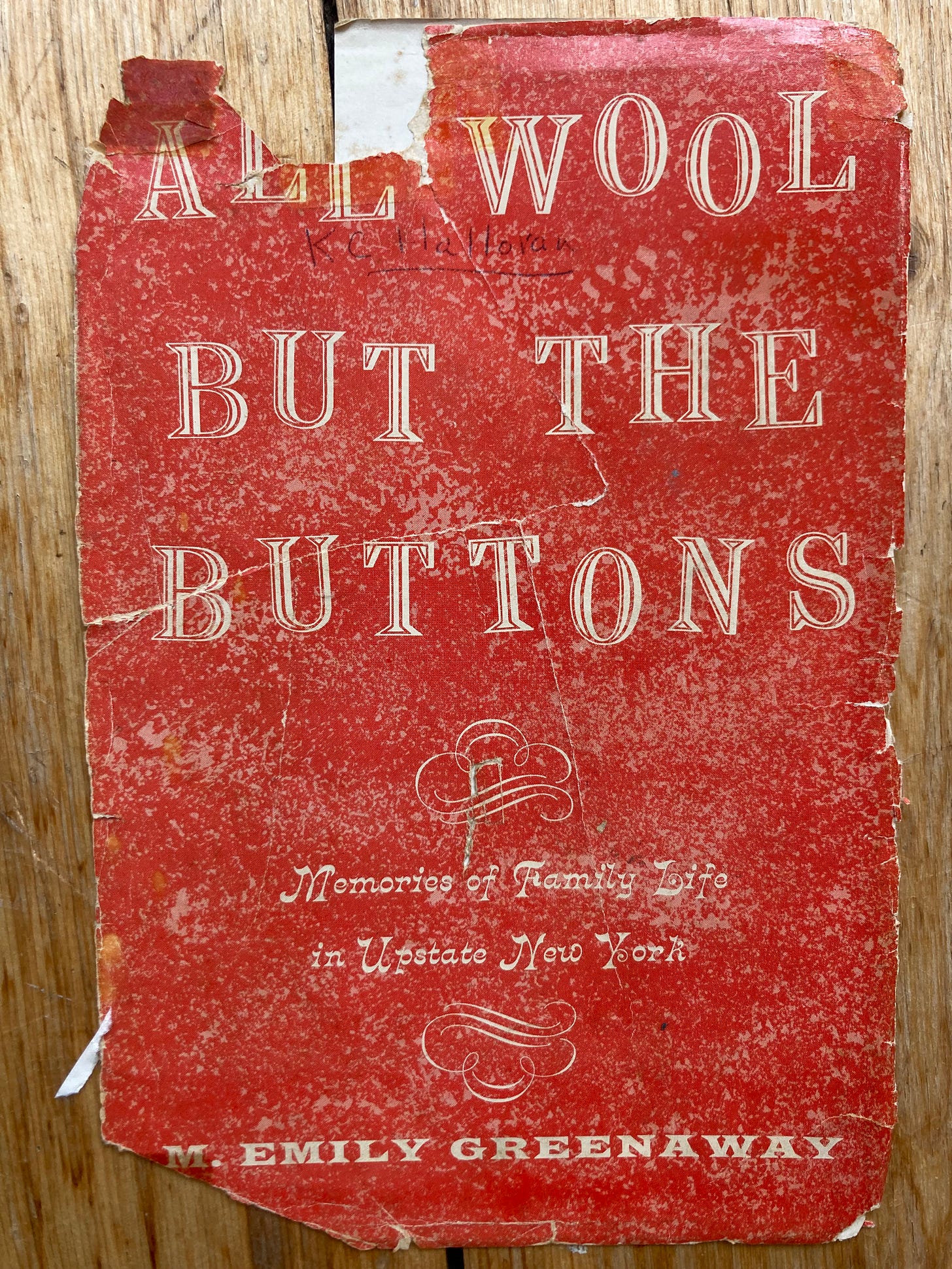

My links to Minnie began with a letter she wrote my grandmother, who had written her about her book, All Wool But the Buttons: Memories of Family Life in Upstate New York. The author wrote back, “Your name rang a faint bell but I remember your brother Charlie very well. As I read his name, I saw him plain as day — not as he looks now, I’m sure, but as he used to look back in School #5.”

Charlie Cole was the first child born in Albany County in the new century, so he would have been closer in age to Minnie than my grandmother, but still, the sentence must have stung. Everyone wants to be seen. Plus, Georgiana Cole Halloran was also a writer, albeit one without a book to her credit. I have all of her papers: newsletters she wrote for her church, nostalgic pieces for women’s magazines, and a six-page memoir about family life dated the year she read Minnie’s book.

These women are enigmas to me. I can read their stories, but I don’t kid myself that I get inside their heads. Words are invitations to connect, but we can’t really get under each other’s skin. The words we send out to the world are filtered, arranged as surely as gluten strands in bread dough. Much as I love reading, I doubt these bridges. There’s so much to be lost in the translation, so much guessing between us. And the guessing is different every time you read something. You find a new meaning, cross into another place.

But when I pick up my father’s papers, I trust the invitation. Here he is! He’s next to me, his words in my hands, in my head. Maybe I feel close because I’m hungry for him — and I can never be as hungry for Minnie, whom I never met, or Georgiana, whom I hardly knew. But I don’t need to look this gifthorse in the mouth. I’m just happy to have him close.

How luxurious to have my father’s words. I keep a few files on his rolltop desk (mine now but always I’ll call it his), and just reread a 1974 letter. He addressed a newly elected congressman by first name, sending a list of several points on national affairs he wanted tended, among them:

More Federal funds should be assigned to getting energy from wind, sun and solid wastes.

A greater effort should be made to cut down on grains used for feed for meat animals by promoting more meatless meals for Americans.

More funds should be provided for mass transit.

I also found a series of math questions that resonate with our moment. He taught high school math, and these word problems ask students to solve the massive, aching problems he saw in the late 1960s and early 70s— the war in Vietnam, campus police squashing student uprisings. I doubt he ever gave them out, but it was nice to read the futile, beautiful wish he made, his hope that the assignments he wrote could do something real.

How many riot police are needed to supplement fifteen campus police if they are to squash a disturbance of 500 dissidents, 25 Black militants and 3 weathermen?

In the stacks I sifted, I also found a letter from an estate sale. I don’t know who wrote this, and the intended recipient is not identified.

Dear ______,

Your lovely letter just came. Glad to hear you eat, sleep and getting a Good Rest. Home here it is so hot, going to work worse and Mother just had an operation on her eyelids, and I just had my upper teeth taken out. So we have real troubles not being able to eat and sleep don’t come easy either. The Mail each Day is Bills and Bills. So you are so lucky you don’t have to go out into the hot city and fight for a few dollars. You need a good rest good sleep and the Place is so beautiful up where you are no Bills to Pay, etc. If you can try to listen to the Doctors so that the Place will help you you have no worries try to stop smoking so much and gain back a little weight…….. You are in heaven but you don’t know it…….Forget the world and enjoy your Rest and We all send our Love and Hope you do as I write Rest Eat Sleep and get fat

Love

Dad

My best guess is this draft was meant for someone at a tuberculosis cure spot in the Adirondacks. I don’t know if it was ever sent, and so I send it to you, dear readers, and hope you are mustering yourselves well for the demands of these days.

Yours, Amy

PS — please take a look at this letter from Emelie Kaye Peine about flooding in Brazil and much more.

Oh goodness, Amy. I loved this one. Wow. It strikes so many of my curiosity cords.