Dear Bread Fans,

I’ve been thinking about sandwiches, another food that made me. I’m known for making pancakes, and for making them since I was a kid, but all of my early kitchen experiences shaped me. War surplus cake, oatmeal cookies — I can see myself reading the recipes at the counter, standing over the bowl, assembling these treats. Sandwiches also helped assemble me.

After I hit a certain age, I made my own lunch, standing at another counter, layering slices of Freihofer’s Canadian Oat bread with baloney and American cheese, or cream cheese and jelly, or liverwurst and cheddar. Baking, and making sandwiches, I made myself.

I can look at my hands, typing these words, and wonder how they hold the smaller versions of me. I see myself gathering ingredients, spreading margarine on two pieces of bread, taking a piece of baloney from its funny plastic dome. Peeling plastic from a slice of cheese. Cutting the sandwich down the middle. The knife went top to bottom, not corner to corner. That’s just the way we did it, and turning a sandwich into two triangles still seems a little fancy.

Do you remember making your lunch? Or did you get lunch at the school cafeteria? The idea of a hot meal in the middle of the day befuddled me, except for pizza on Fridays, which I occasionally bought. This contradicts the cookbook intel I read about lunch.

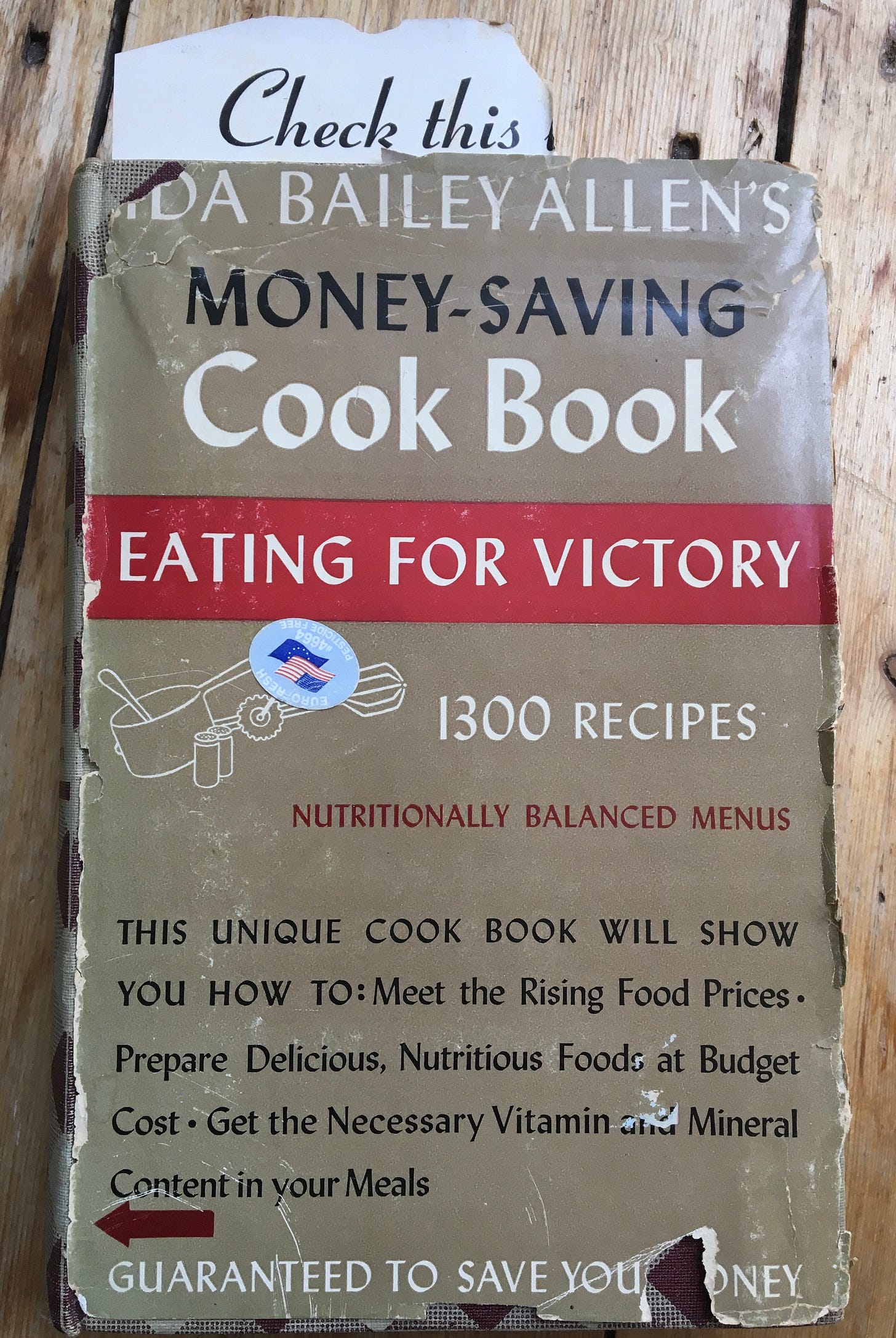

“The home-packed lunch may be supplemented by a hot beverage or a hot main dish selected from the school lunch counter. But if no cafeteria is conducted at the school, the child’s lunch kit must include the necessary one hot food in a meal. This may be a hot milk beverage or a milk soup, or it may consist of a hot creamed vegetable or “meat dish” made with a cream sauce thin enough to be carried in the thermos bottle.”— from Ida Bailey Allen’s Money-Saving Cook Book: Eating for Victory, 1942

The rationale was that the foods must resemble what the child would eat at home, or else it would not “furnish adequate nourishment.” I like how familiarity and nutrition were linked. This book was published when my parents were kids, a time when many elementary schoolers went home for lunch. Cold sandwiches, the ideal midday meal to me, were not yet — at least from this guidance — accepted.

The variety of foods recommended for “carried” lunches, as Ida Bailey Allen called them was wide. Vegetable suggestions were whole tomatoes, celery, and radishes, plus coleslaw, potato and other salads. Soup ideas were cream of tomato, spinach, Lima bean, onion, celery, split pea, potato and onion, vegetable chowders, alphabet-noodle, or chicken noodle.

Practical Cookery and The Etiquette and Service of the Table gives a different approach to sandwiches. The last third of the book is focused on etiquette and food service, but there’s no discussion of how to compose a nutritious lunch box. The sandwich and canape chapter covers the construction of these foods, and I think you’d like to see what was said about bread.

“Choose bread of any desired kind. Graham, whole-wheat, nut, rolled oats, brown, or raisin bread, or combinations of these, are good choices. Special sandwich loaves are often desirable. For most sandwiches the bread, in order to cut well, should be about 24 hours old. Rolled sandwiches, however, should be made from fresh bread, as this does not break easily when handled. For a dainty party sandwich, cut 1/8 inch slices of bread and remove crusts. If sandwiches are to be cut into fancy shapes, it is more economical to cut slices lengthwise of loaf. Cut bread thicker and retain crusts for sandwiches for picnics, lunches, and everyday use. Bread may be toasted for variety. Toast is especially good for cheese, bacon, and tomato sandwiches.” —from Practical Cookery and The Etiquette and Service of the Table, 1941

The Home Economics Department at Kansas State College printed many editions of this textbook, and I have the 19th edition, published in 1941. As a revision of previous editions, and printed prior to the US entry to war, no wartime information made it between the covers. Allen, however, emphasizes that by ‘manning the kitchen,’ women can help win the war.

Allen also urges people to only use enriched flour, a new product. The military began using flour enriched with vitamins and minerals in 1942, and in 1943, mandated consumer use of it. The same rule banned sliced bread, to reserve metals used in manufacturing, and prevent waste; sliced bread staled more quickly because preservatives were not as advanced as they’ve become.

Sliced bread had only been on the market since 1928, but despite its relative novelty, there was a public uproar about the ban, and shortly afterwards, the ban was removed. In the 15 years eaters had access to pre-sliced bread, it became a basic food. And with the war years, men were overseas and women who didn’t normally work out of the home were doing so. Sandwiches were easy food for people, in particular kids, to fend for themselves in ‘unmanned’ or ‘un-womanned’ kitchens.

These few slices of bread history show that sandwiches, as I understand them, were really born just before my parents. How can something that feels foundational — making a sandwich from bagged bread — be so modern? The experience seems a primal memory, almost universal. Yet how I emerged was very specific to a stripe of time and a certain place.

The things we do define who we are.

I’m a kitchen oriented person, so of course I can see myself becoming me right there, at the counter, reading cookbooks, and taking a tray of cookies from the oven. But I bet a sense of self could have emerged in the kitchen even if your life doesn’t revolve around making food. I’d like to know.

Do you remember becoming yourself as a kid? Maybe the manufacturing occurred at the piano, or digging in the yard, or riding your bike. Or maybe, your identity began as you poured a bowl of cereal, and carefully added the right amount of milk. Please tell.

Yours, Amy

More Reading

The Food Historian, Sarah Wassberg Johnson loves Ida Bailey Allen too! Check out her posts here.

Here is a digitized copy of Practical Cookery and Etiquette and Service of the Table, no named author, Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences, 1941.

Ida Bailey Allen’s Money-Saving Cook Book: Eating for Victory, by Ida Bailey Allen, Garden City Publishing, 1940, 1942.

I loved this! Growing up in Battle Creek, the self proclaimed Cereal Capital of the World, I’ve always been fascinated with the foods we eat. My lunches were at home until school lunches were introduced in the late 60s. Tomato or chicken noodle, really any of the canned soups paired with baloney, peanut butter, grilled cheese or tuna salad sandwiches. Then we took it up a notch with fried baloney or fried egg sandwiches. I remember my father feeding a huge roll of baloney into a grinder clasped to the table edge. He then added mayo and pickle relish.

Great post 📯. I love sandwiches and history. Also thanks for linking the texts of the cookbooks. How about a slice of sourdough, some hummus and red pepper?