Dear Readers,

A week ago, Sunday, I was waking up on the train in Indiana. Snow dusted the fields and farms I saw out the window, and I was about to visit Liberty Hyde Bailey's childhood home in South Haven, Michigan.

I call LHB my dead boyfriend because I have a terrific thing for his words. At the turn of the last century, he was wildly popular, and his publisher, Macmillan said they would take anything he wrote. It's hard to comprehend how someone who wrote about farming and gardening, and a whole lot more, could command such an audience. But he did.

I fell in love with him in 2014, as I was researching an encyclopedia entry about the cooperative extension program. I read a zillion books and articles to write a single paragraph. I'm not sure which book introduced me to Bailey, but he was instrumental in creating Cornell's extension program, so there's no way I couldn't have found him on that quest.

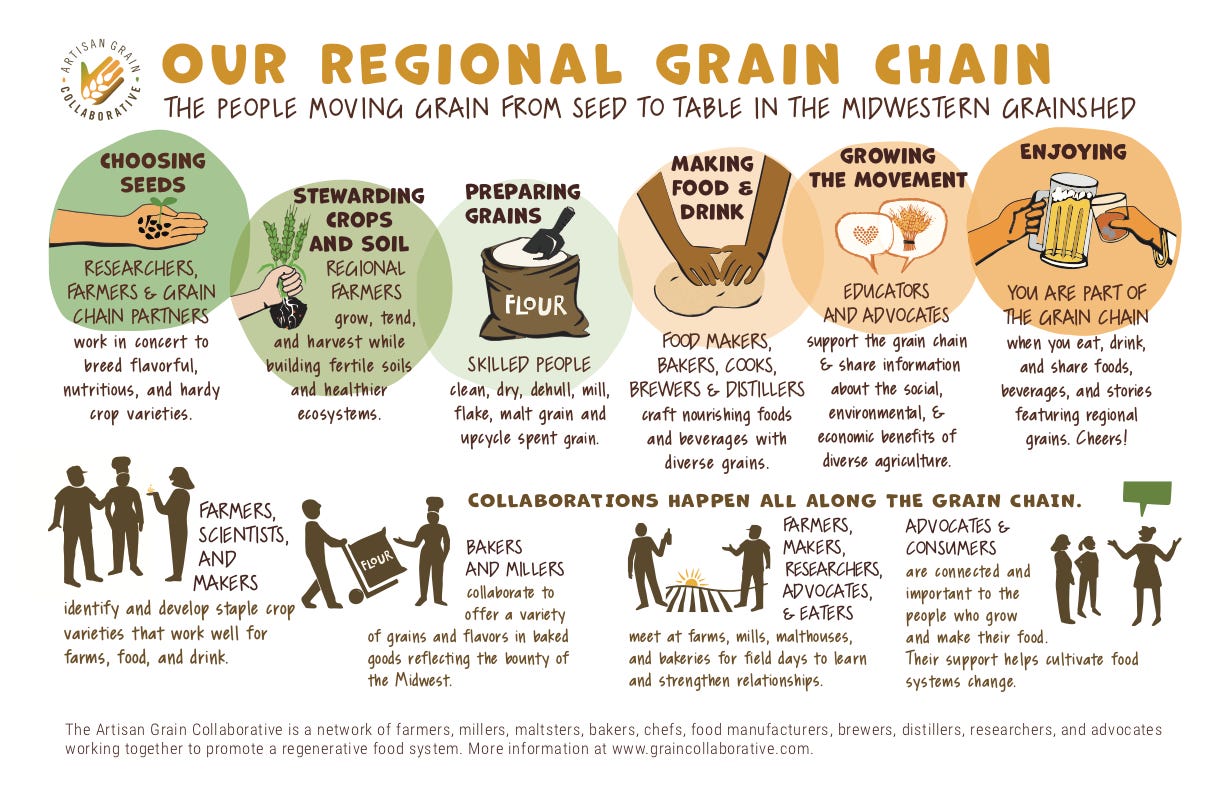

Cooperative extension is the bridge between state agricultural colleges and farmers. In the process of researching my flour book, I met extension staff who were involved in rebuilding regional grain systems. People like Ellen Mallory at the University of Maine helped me understand what a big leap it is for farmers to work beyond established marketing schemes. Grain field days throughout the Northeast were organized by or with cooperative extension; since I learned so much from extension, I wanted to understand how this generous network was built.

Formally established by the federal Smith-Lever act of 1914, extension work began much earlier as land-grant universities realized they needed mechanisms to invite and include farmers. In New York, it started with state funding and Liberty Hyde Bailey directing, in 1894.

The language of those early extension bulletins, and the Nature Study pamphlets, is simple and declarative, yet inviting. Here are some samples I love. The first is the beginning of a November 1900 edition mailed to farmers enrolled in a reading course. The second segment is from a nature study guide for teachers, circa 1898.

The Soil: What It Is.

1. The basis of soil is fragments of rock. – As the earth cooled, the surface solidified into rock. The processes of nature have been constantly at work in breaking up this rock and making it into soil.

2. Weathering is the great agency in making rocks into soil. – Rain, snow, ice, frost have worn away the mountains and deposited the fragments as soil. Probably as much material has been worn away from the Alps as still remains, and this material now forms much of the soil of Italy, Germany, France, Holland. Our own mountains and hills have worn away in like manner.

3. Weathering is still active. – All exposed rocks are wearing away. Stones are growing smaller. The soil is pulverized by fall plowing.

The Birds and I.

The springtime belongs to the birds and me. We own it. We know when the Mayflowers and buttercups bloom. We know when the first frogs peep. We watch the awakening of the woods. We are wet by the warm April showers. We go where we will, and we are companions. Every tree and brook and blade of grass is ours; and our hearts are full of song.

Bailey’s strong bond with nature developed in western Michigan. Liberty Hyde Bailey Senior, his father, was a pioneering orchardist who grew up in Vermont. Liberty Hyde Bailey Jr. was four and a half when his mother, Sarah Harrison Bailey died in 1862; this loss and a childhood of relative aloneness helped glue him to the woods and world around him.

I feel like I have known Bailey and his sensibility nearly forever, and I've tried a few times to see the place that shaped him. A meeting to discuss the AGC grain chain infographic was the excuse that made the trip finally happen.

I’m glad I made it by train. I got on the train in Schenectady Saturday night, and slept and didn't sleep as the Lake Shore Limited made its way west. Amtrak doesn’t rule the rails, except in the Northeast corridor, so journeys halt when freight trains need passage. The slow pace rearranged my sense of movement.

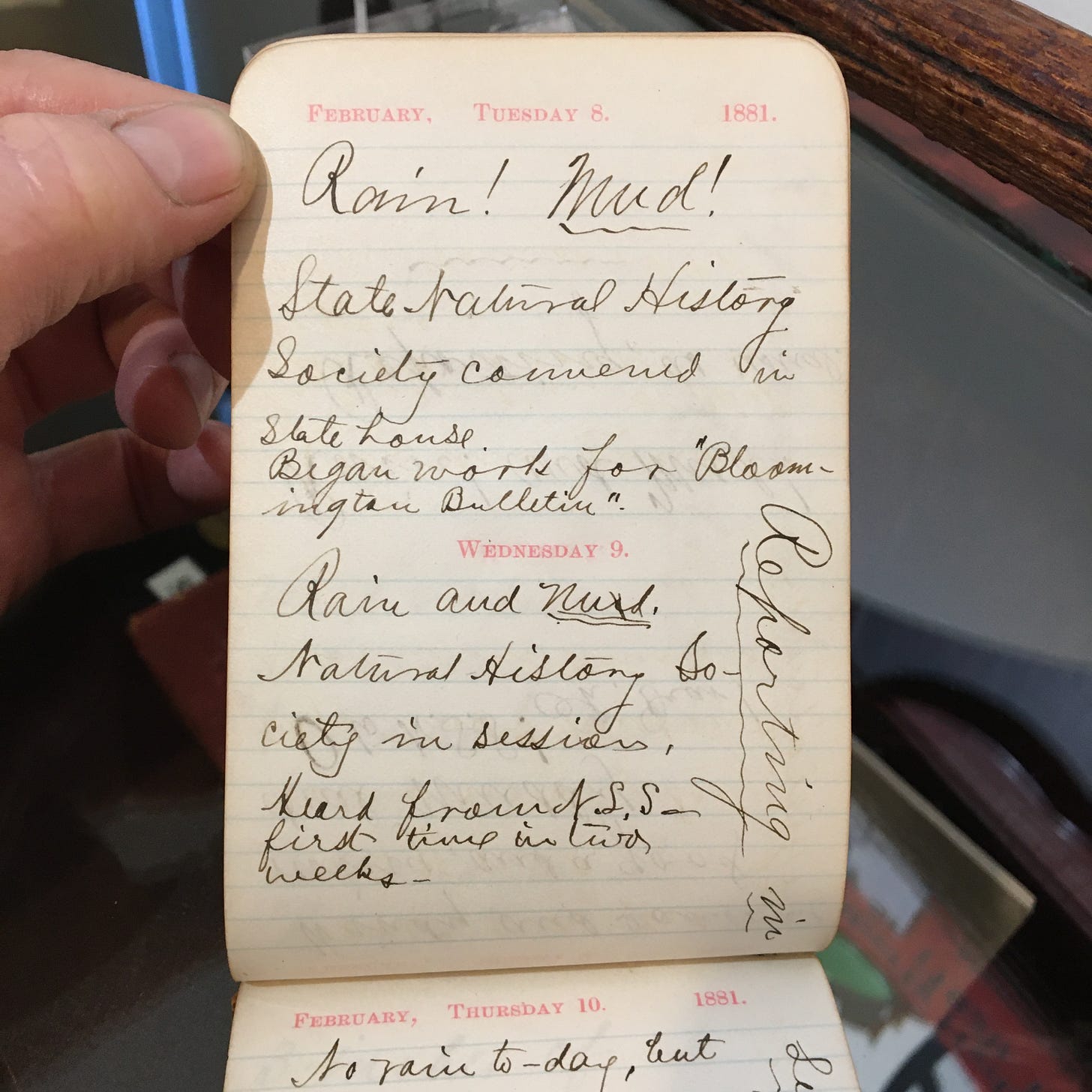

I got home Tuesday afternoon but it's taken me all week to return. I’ve been in limbo, floating in where I was: at Granor Farm and talking about grain education; walking through the little town of Three Oaks, Michigan at sunset, surprised at the flatness and lack of trees; holding the diaries that Liberty Hyde Bailey kept when he was 14 and 23. Both are filled with notes about the weather. Mud. Muddy. Cold. Hot. The more recent diary mentions his work, which at the time was newspaper writing and sales; he also notes when his fiancé writes him, and when she does not. So sweet!

I am in Troy but thinking about LHB and his home place. I stood in the room where the family gathered as his mother died. I studied his signature in primary books, absorbed family photographs, and touched his father’s hoe. I looked at the books that he read as a child, and the botany titles that influenced him, trying to get a sense of everything that shaped his voice.

There is something very welcoming in his style. The way he articulates facts and ideas is like being served breakfast by your mother on your birthday – a celebration of life. How did he become so very able to connect with readers? Did he just love life and people and need to reach out to us?

Liberty Hyde Bailey had a vision of life and farming that had individuals and community at the core. He believed in education as a means to link farmers to their land and their work. By developing a sympathy with nature, farmers would learn to understand the world around them and approach problem-solving from an intimate, knowledgeable stance. Developing rural communities was important to him. If his visionary ideas led the way for agriculture in the 20th century, we would have a very different food and farming world. Instead, commercial interests ruled, and monocropping became our agricultural habit, at the expense of diversified farming.

Bailey was instrumental in developing the Nature Study Idea, which is a similar invitation for people to find unity with their environment. One thing that struck me in my early fascination with him was that he influenced environmental writers that are more famous: Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, and Wendell Berry. His words seem so heroic to me. Why, I wondered don't we salute him?

Bailey was a plant rockstar, but he liked studying plants and helping people, not being on a stage. America likes icons, but he resisted that, and so his fantastic writings haven’t gotten the notice that I think they should.

A few determined scholars are changing that. In 2015, John Stempien, the former Bailey House Museum director who gave me a meditative tour (thank you!), and John Linstrom helped get The Holy Earth reprinted for its centennial. These two John’s worked together on the Liberty Hyde Bailey Gardener’s Companion, a luscious dive into his garden writings. (I wrote a blurb for it that is printed on the back cover.) And The Nature Study Idea’s reissue is underway, part of Cornell University Press’ Bailey Books.

I encourage you to visit Liberty Hyde Bailey in some fashion. The Bailey Project is a good digital place to begin.

Yours, Amy

OMG I love Liberty Hyde Bailey! He really transformed the ag program at Cornell and was supportive of the home economics department there. He was also involved in food policy in New York during World War I. Crazy prolific author, super cool guy.

Thank you Amy, I love your devotion. When I worked in a school garden with kids and plantings, Bailey was an inspiration and his words were companions.