Invalid Cookery

Retrieval #2

Dear Readers, welcome back to this exploration of the concept of retrieval.

Today, Ellie and I are thinking about feeding the sick.

I was in my 20s when I started reading old cookbooks and guffawed at the chapters on Invalid Cookery, or Feeding the Sick. I was dumbfounded that this was a category! I dismissed it as old timey stuff, Laura Ingalls Wilder-ish, nothing we really needed in the 1990s.

I wasn’t oblivious to healing foods. I knew the BRAT diet because my father often went on it, trying to tame his active bowels. And when my siblings and I had our own stomach woes, Mom offered Bananas-Rice-Applesauce-Toast. Since we never had invalids in our house — well aside from some serious strains and a few breaks that temporarily set us up in bed — I figured that cooking for sick people was a 19th century thing.

As I slide into age, of course, I see the naivete of my dismissal. When I am ill or ill-at-ease, I find I’m feeding myself what my mother fed herself when she didn’t feel well: saltines and butter. Or I’ll make what she made me – peanut butter toast cut in strips, top to bottom.

I don’t remember my father wanted when he was sick, but I have this little feeling knocking on my door. A feeling of what he leaned towards in general, like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich made with Peter Pan peanut butter, grape jelly, and butter on each slice of bread, first.

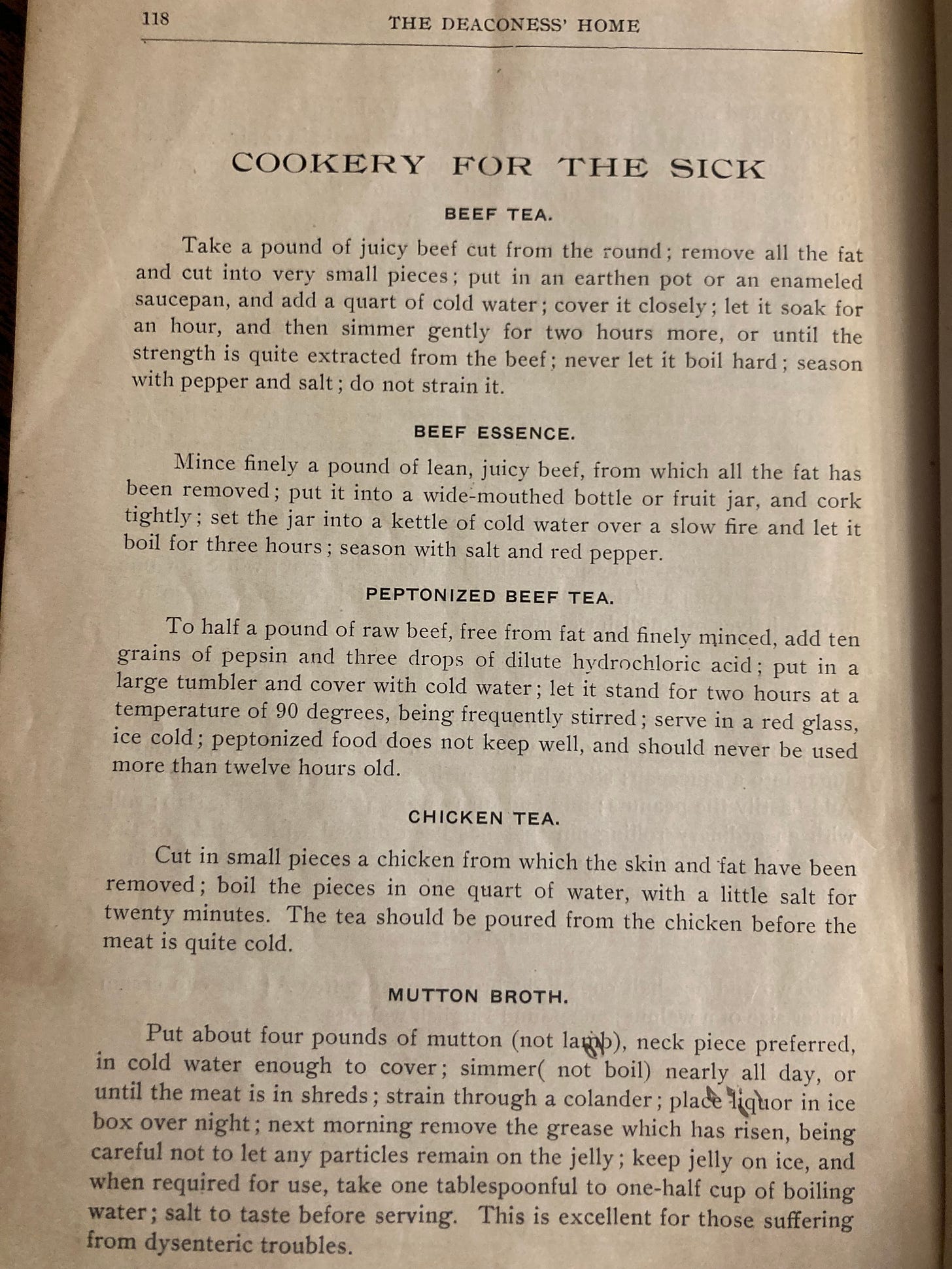

Reading up at the Hart Cluett Museum today, I returned to the Deaconess’ Home Cookbook, which was written and published here in Troy, NY in 1903.

I love this recipe from the Cookery for the Sick section:

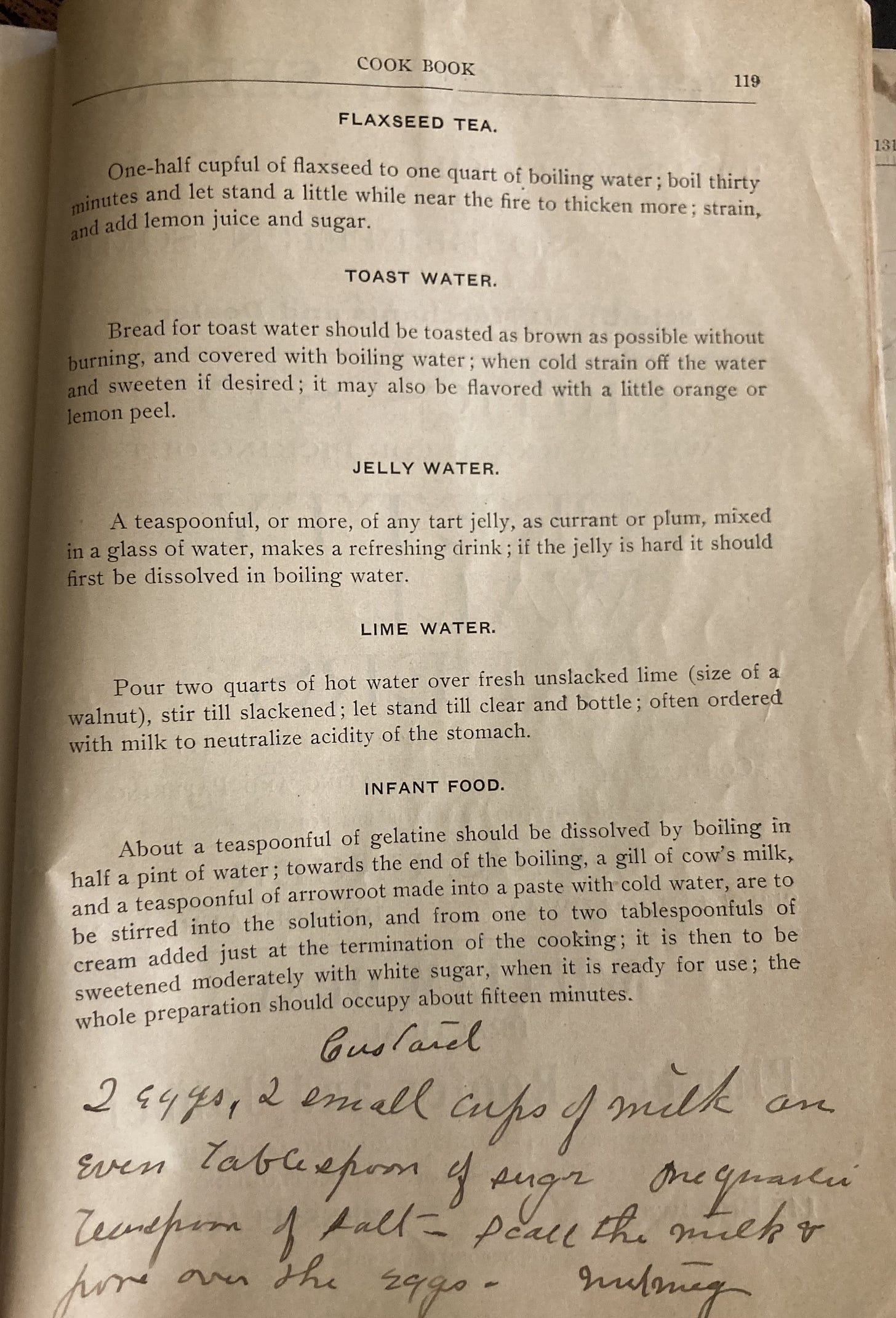

Toast Water.

Bread for toast water should be toasted as brown as possible without burning, and covered with boiling water; when cold strain off the water and sweeten if desired; it may also be flavored with a little orange or lemon peel.'

Bear in mind that in 1903, most toasting took place over a flame. Electric toasters were just in the midst of being invented, and few houses had electricity.

The first General Electric toasters were lovely, dangerous things, lacey-looking wires heating the bread right before your eyes. These prettily designed machines were meant to decorate the breakfast table of the upper classes, where they could Marie Antoinette their way through the task; the cost of a toaster was significant, about a hundred contemporary dollars! Amazing how something mundane in modern America was once extravagant.

—Amy

And now for some words from Ellie:

When we are too weak to even lift an arm, we can feel very deeply the smallest of gestures. Maybe so deeply that we carry with us and pass it on. A taste becomes a tool of physical and emotional healing.

When my dad was on his last days we fed him fine cornmeal broth, almost to the end. It was the only thing his body didn’t reject. It was what he taught me to make for him. And I was being healed of a broken heart watching him take a few sips.

With me, when I got sick, my mom would make a thin rice savory porridge with tiny cut vegetables– “not too much salt and cooked without fat,” she explained. “Comida de hospital” or hospital food I thought. But it was so delicious as I could taste what a tiny carrot tasted like and the warmth of a potato, helping me feel like I was eating, reacting, and strengthening.

My husband's Russian family passed down to him tea healing. When he is sick or someone is sick he calls out for unsweet strong black tea “to firm the stomach.”

Recipe for Broth, Caldo :

4 cups of water, 1 litro de água

⅓ cup fine cornmeal, ⅓ copo de Fubá

Salt to taste, Sal a gosto

1 egg beaten, 1 ovo batido (if you feel up to it, se quiser)

My dad showing me in this photo from August 13, 2024 how he likes to dissolve the fine cornmeal (fubá mimoso was his favorite) in a little cold water to avoid any lumps, then add more water, pinch of salt and simmer to thicken and until the taste of raw cornmeal is gone. Stir in the egg. That day he did.