Dear Bread friends,

When I started a food blog, I named it Home Economics. A young mother in the earliest part of the 21st century, I fantasized my blog might get me a book deal. (!) I didn’t plan on explaining how home ec classes made me feel like I wanted to hide. I didn't see sewing and cooking as academic subjects -- plus who wants to talk about periods with a teacher? Home Economics was just a kitschy title for the mailbox that delivered my family cooking letters to the world. Or maybe I was slinging mud at myself for writing about food instead of focusing my energies on the Great American Novel.

My husband once noted that the blog’s title didn’t deliver because the contents didn’t explore the economics of cooking. But I was too embarrassed to talk about buying factory tortillas and bricks of cheddar cheese. I needed to put a locavore-ish face forward, like my blogging peers. In addition to all these walls, I don’t think I really knew what home economics was until last Sunday, when I finished reading Laura Shapiro’s “Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century.”

I picked the book off my shelf as I was finishing my last bread letter. The Internet was only giving me hints about Miss Maria Parloa and Mrs. D. A. Lincoln, the women whose cookbooks I was using to interpret flour in the 1870s. I knew I might have a book that had something useful and, happily, I found an entire chapter about the Boston Cooking School, which each of these women claimed to have founded. Neither one of them actually did.

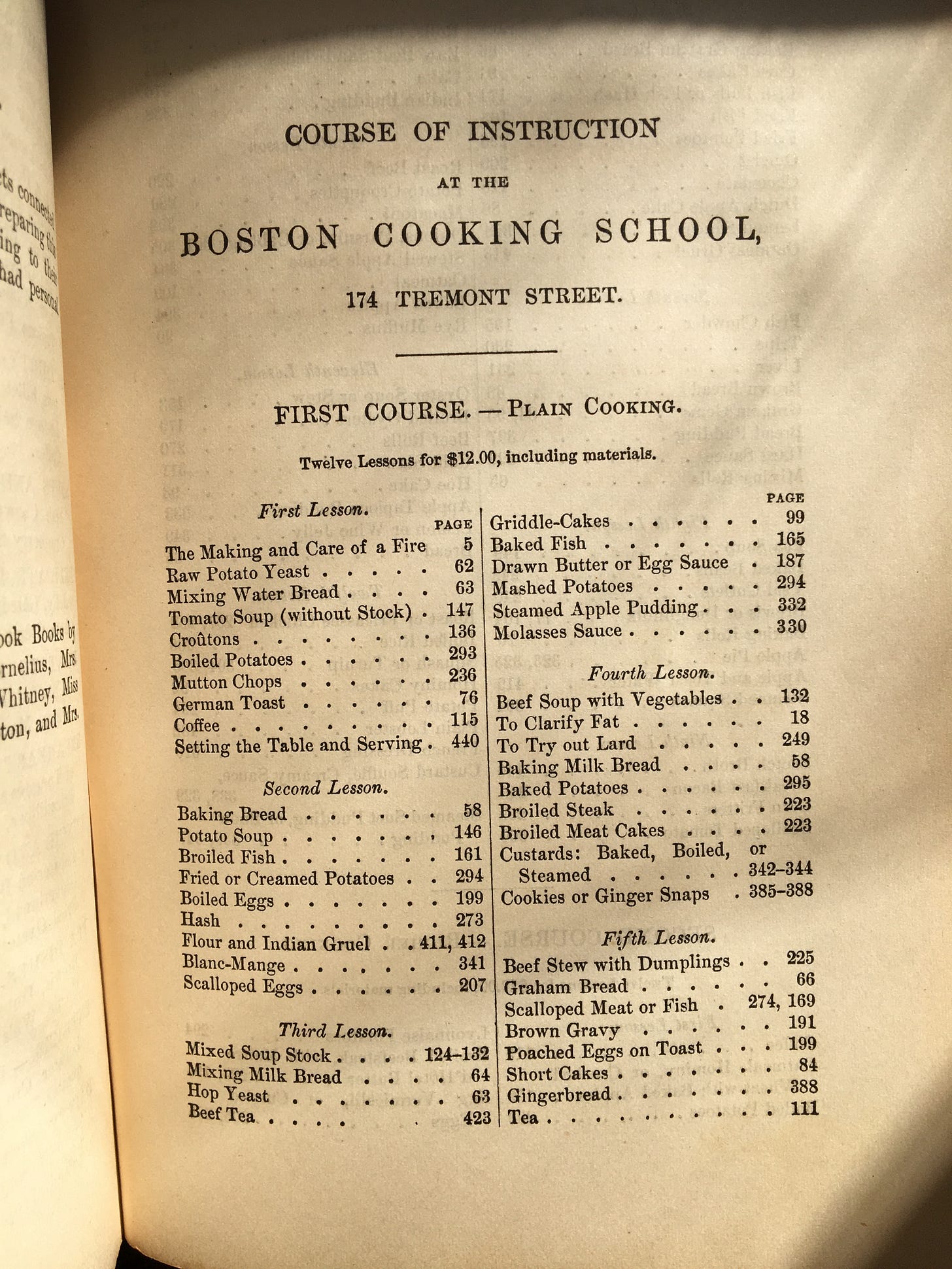

The school was a project of the Woman's Education Association of Boston, whose Committee on Industrial Education began considering starting a cooking school in 1873. The idea was put on hold because they didn't know what to do with the food that students would prepare. Shapiro names the irony that the charitably-minded founders didn't consider feeding the students, even though the lessons would be directed to young women from working class families. Apparently, the idea was revived only after similar efforts in New York City got a lot of publicity. Jealousy can really spark action.

“The Boston Cooking School was founded in 1879, a time when the national zeal for social progress and moral reform was rampant. Reformers of every sort had always found Boston a most congenial place in which to apply their theories, and for generations of women, Boston had long been a city receptive to projects representing the various stages of American feminism." (Shapiro 48)

Organizers hoped to get Miss Maria Parloa to teach, because she helped start the New York Cooking School, but she was already a highly respected teacher, and could command high pay. Instead, they hired a very inexpensive Irish immigrant named Joanna Sweeney to teach the bulk of the classes, and paid Miss Parloa to give occasional lectures. The food, it was agreed, would be sold at cost to “such poor people as would come for it, bringing their own baskets and kettles, and to such of the scholars as wished to buy it.” In class, students would taste the food so they would understand the lessons.

The early years of the Boston Cooking School were a mishmash of intentions and operations, with a school in the Italian neighborhood set up to serve charitable intentions, and another location geared to cooking lessons for the mistresses or hired help of wealthy households. Joanna Sweeney was never going to suit the upper crust goals, so a more appropriate, middle-class teacher was sought. Sweeney ended up training Mrs. Lincoln, who became quite a fixture in cooking instruction. Eventually, she left the school to pursue a profitable career on her own, and after a while, Fannie Farmer, who had attended as a student, became its principal.

Boston wasn’t the only school grappling with the many social layers it needed to serve. Cooking schools were committed to teaching more than skills; they were also meant to “civilize” people through cooking. The domestic moralism of the mid-1800s eventually became the domestic science movement of the late 1800s that cooking schools included. Reform-minded women had honorable ways to leave the home, and devoted themselves to figuring out how food could save the poor. Domestic science became scientific cookery, and the profession helped America fall deeply in love with technology, uniformity and efficiency. Scientific cookery studies matured and expanded into home economics, and the field was embedded into home ec departments at colleges and universities; this created an acceptable educational channel for white women, a parallel but unequal path that let higher ed believe they’d handled the woman question. Coincidentally, or not, home economics departments grew at the same time as food manufacturing did, and the graduates slid seamlessly into careers promoting this emerging industry, as described in the following paragraph.

“As advertising became a more crucial factor in the economics of magazine publishing, food columns increasingly reflected commercial interests, and scientific cookery itself settled comfortably into the service of the industry. Food ideas that were developed in the company kitchen, and food ideas that spring from the independent experts, were so compatible that together they set in motion what both had desired: a single cuisine for all of middle-class America. New products, new methods, and new combinations were quickly absorbed into the teaching of the most famous cooks and home economists, whose culinary imaginations were well primed.” (Shapiro 203)

I can’t do this book justice here. I hope you’ll read it because it begins to address questions I’ve been asking myself for decades, starting on my blog. Why did America hand over cooking, one of the most intimate forms of care, to industry? Why don’t we outsource laundry rather than feeding each other? Why did I have to teach myself how to cook, from PBS cooking shows and cookbooks from the library, rather than learn from the women in my life? How come American home cooks lost confidence?

Here’s one last quote, because it seems to answer some of my riddles. “Between World War I in the 1960s, generations of women were persuaded to leave the past behind when they entered the kitchen, and to ignore what their senses told them while they were there.” (Shapiro 215)

How do you find agency and authority as a home cook? This is the conversation I keep having with my friend Ellie, and one I’d like to have with you, too. I’d love to hear what you think.

Yours,

Amy

Books mentioned:

Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad. Henry Holt, 1986.

Lincoln, D. A. Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book. Roberts Brothers, 1886.