Bread Windows

The ingredients of history

Dear bread,

Do you know how many backflips we do for you? I wonder if you have a glimmer of the gleam you put in our eyes. Each time dough becomes a loaf, making our hands float, do you get a butterfly in your big bread heart?

Maybe you are content to be an object, and don’t need to know what we feel for you. Whatever the case, you’ve got my attention.

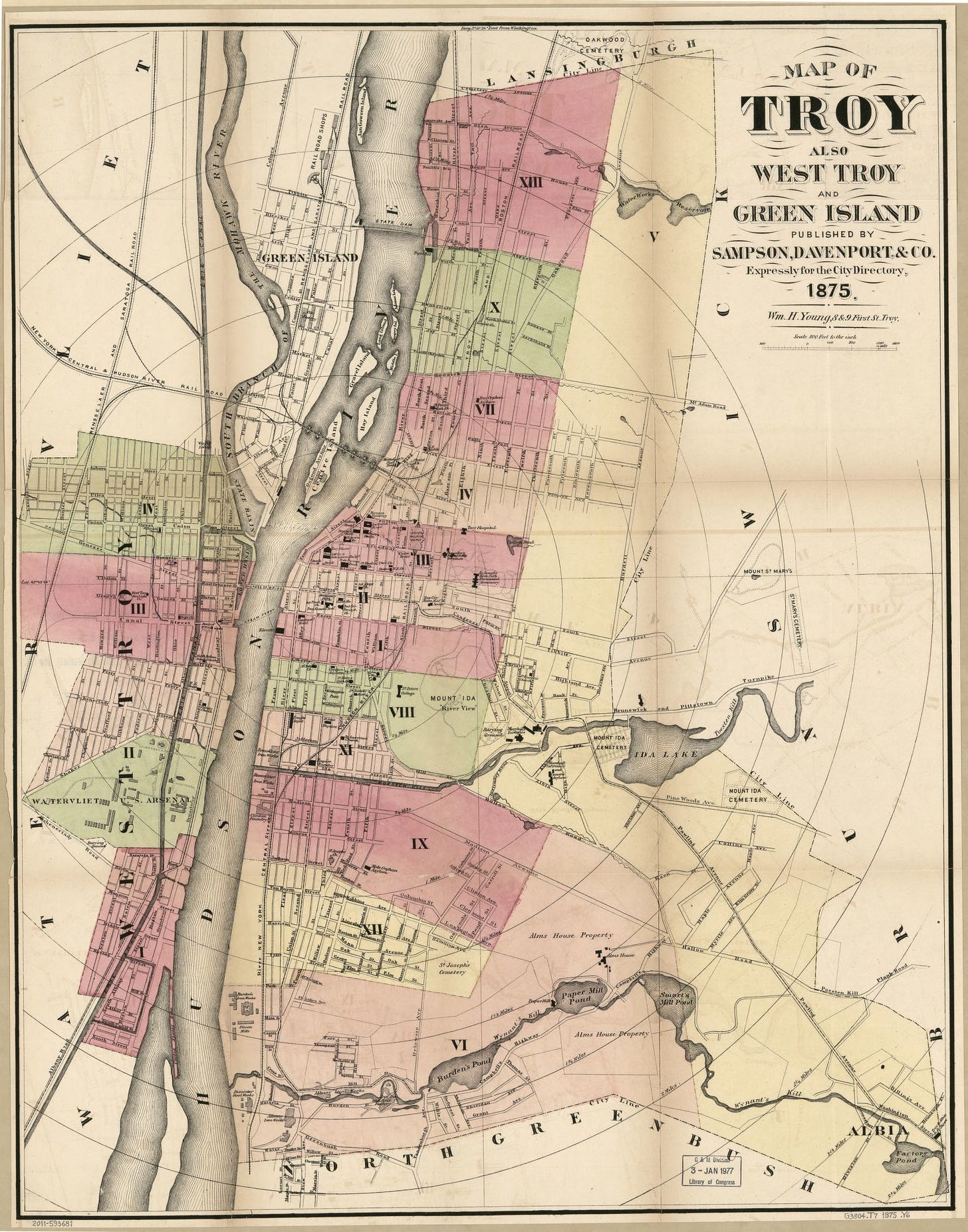

These days I’m trying to make sense of American bread by learning more about American times. One window I’m studying – because I look in a lot of windows at once – is when Sylvester Graham published his Treatise on Bread, in 1837. What, I wonder, did my city of Troy, New York look like then? What was happening to the place that made me?

Troy and the village it would annex, Lansingburgh, were separate centers of manufacturing and trade on the Hudson River, 150 miles north of New York City, and just as far south of Montreal. The village of Lansingburgh was a trading port for grains and other food; a site of shipmaking, and making brushes and oilcloths – a precursor to linoleum flooring.

Troy’s goods were iron and steel – lots of farming tools, stoves for heating and cooking, and every metal thing else. Detachable collar businesses were just beginning, the brainchild of Hannah Lord Montague, whose fastidious husband Orlando wanted 2-3 clean shirts a day. Tired of hand-washing that many shirts, she experimented and came up with an incredible invention in the days before automated washing machines — collars that you could launder separately.

Industrialists in both spots were amassing fortunes, money that would build the Victorian house where I lived as a kid. The slate sidewalks I hopscotched were still snug in a quarry, and Herman Melville was about to move with his family just a few blocks from where I’d eventually eat, play and sleep.

Herman Melville’s father died in 1832, and his mother, Maria, relied on her relatives and sons for income. Their 1838 move from Albany was caused by hard times, both personal & international.

The Panic of 1837, a financial crisis that would last five years, sent them across the river. Herman was 19 when they moved to the house that is now the Lansingburgh Historical Society. Researchers there have posted a detailed list of his area activities – including links to early writings published in a local paper.

Melville biographer Hershel Parker’s article The Unemployable Herman Melville more directly investigates the impact of the economy on his career. After striking out on many job attempts, Melville went to sea in January 1841. He wrote his first books, Typee, Omoo and Redburn here. I like to look at the windows of his house, and imagine him looking at the water full of ships.

Those early books were successful, but Moby Dick capsized his career. The great white whale of a book confused and angered critics and the public.

I used to joke that the family’s social fall from Albany to Lansingburgh was part of the reason Herman Melville found rage and put it in Ahab. That was before I learned how dramatic the Panic of 1837 was. I knew an ingredient of his life, and naively applied that to his story — like trying to make bread from a list, without guidance on equipment & methods.

Bread history is ovens, flour, governments, class strictures, gender roles and heating fuels. History is context, not just dates and facts. One interpretation of Moby Dick is that it makes visible work that happened offshore, far from people’s minds. The brutal work of whale fishing was wretched, lonely and dangerous. Crazy captains and shipmates faced horrible circumstances in the quest for oil that lit lamps & made candles for homes & industries.

The big book is also about whiteness and slavery. Melville was born just after New York State declared the last slave would be freed in 1827. The world he knew was full of racial hierarchies; he was of Dutch blood — and his grandfathers on both sides were Revolutionary War heroes — and his rich ancestors likely owned slaves. He would have heard stories of his uncle’s stable being set on fire, and the two slave girls who hung for the crime. This story is news to me, uncovered by a friend who is researching our region’s Black history.

If I fancy myself a writer who has inherited something from my fellow townie, all of what was in him is in me, too. I need to find where the Hanging Elm was in Albany. To think about how writing can hold human miseries, and what shape my writing can take to reveal the modern quests we send people on, to do our dirty business out of sight. Can I write a loaf of bread that is a Moby Dick?

Until the next time, Amy

Related readings:

Workers World article on Hanging in Albany

Panic of 1837, from The Economic Historian website

Historian Jill Lepore's New Yorker article on Edgar Allan Poe

Published writing: