Dear bread friends,

Every once in a while, I get nostalgic for when I would carry a friend in my head for days, composing a letter. In my teens and 20s, I always had a letter going. When I finished one, I would start another. That changed once I had kids and many of my routines vanished. So, I can’t blame the loss of this habit on my attachment to social media.

The last time I had this lament, I realized that I still carry and communicate with my loved ones. My siblings send and receive a lot of cat texts. My work pals at the Artisan Grain Collaborative share articles, and occasional pictures of beautiful flowers on a text thread. My steady correspondent is Ellie Markovich. A year ago, when a dear friend of hers died of cancer, I took the bold step of asking if I could text her at dinner time. I knew that each evening, Phyllis had texted, “What’s for dinner El?”. I knew I couldn’t take her place but I dared to offer myself. Ellie accepted, and we have been exchanging photos daily.

At dinner, I pose my plate, or send a tableau of the dinner dishes: often it’s greens, rice, baked tofu and some kind of sauce based on a recipe she gave me. I show her what I’m baking. I take her along on walks, looking at things with her in mind. This peach. This set of leaves. This road. I show her small waterfalls, and try to catch the moving water of a stream. She shows me mushrooms and tall Tamarack Pines in all seasons. She shows me her garden and I show her my family, who wave to Ellie and give her legitimate smiles, and sometimes crazy faces. “How do you get them to pose for you?” She asked the other day. Her family doesn’t want to be in her pictures, but I suspect that has something to do with her being a photographer.

There’s great magic in having an audience. I pay closer attention to my surroundings as I look for things I want to share. Knowing she is waiting, as I am, for a snapshot, is really nice. I feel connected to her throughout my days, and that is steadying.

In art, you are supposed to not consider the viewer or reader; these thoughts can be a distraction, goes the logic, from true expression. Yet Kurt Vonnegut suggested people write to one person. He used to write to his sister, and when she died, he lost his footing. I’m not sure who you are here in my audience, or what you want to read. But I do have you in mind, dear readers, when I think about bread, and that is frequently.

What I’ve been wanting to share is Ellie’s wonderful approach to baking without a recipe. We led a class about this at the Kneading Conference, “Baking by Touch, Not Tech.” We had a fun romp through our kitchens over zoom, exploring this process that Ellie developed. Basically, it is a measurement-free sourdough loaf that relies on and supports your understanding of making bread dough.

I’m intrigued by the method because I’ve always been an eyeball baker. I was too impatient to get out my measuring cups, and now I’m glad to have an excuse to not get out my scale. The approach is inviting us, just as bread has always invited us, to bring our full selves to make bread. Each loaf becomes a snapshot of a day, a moment, an ephemeral record of your hands and your life.

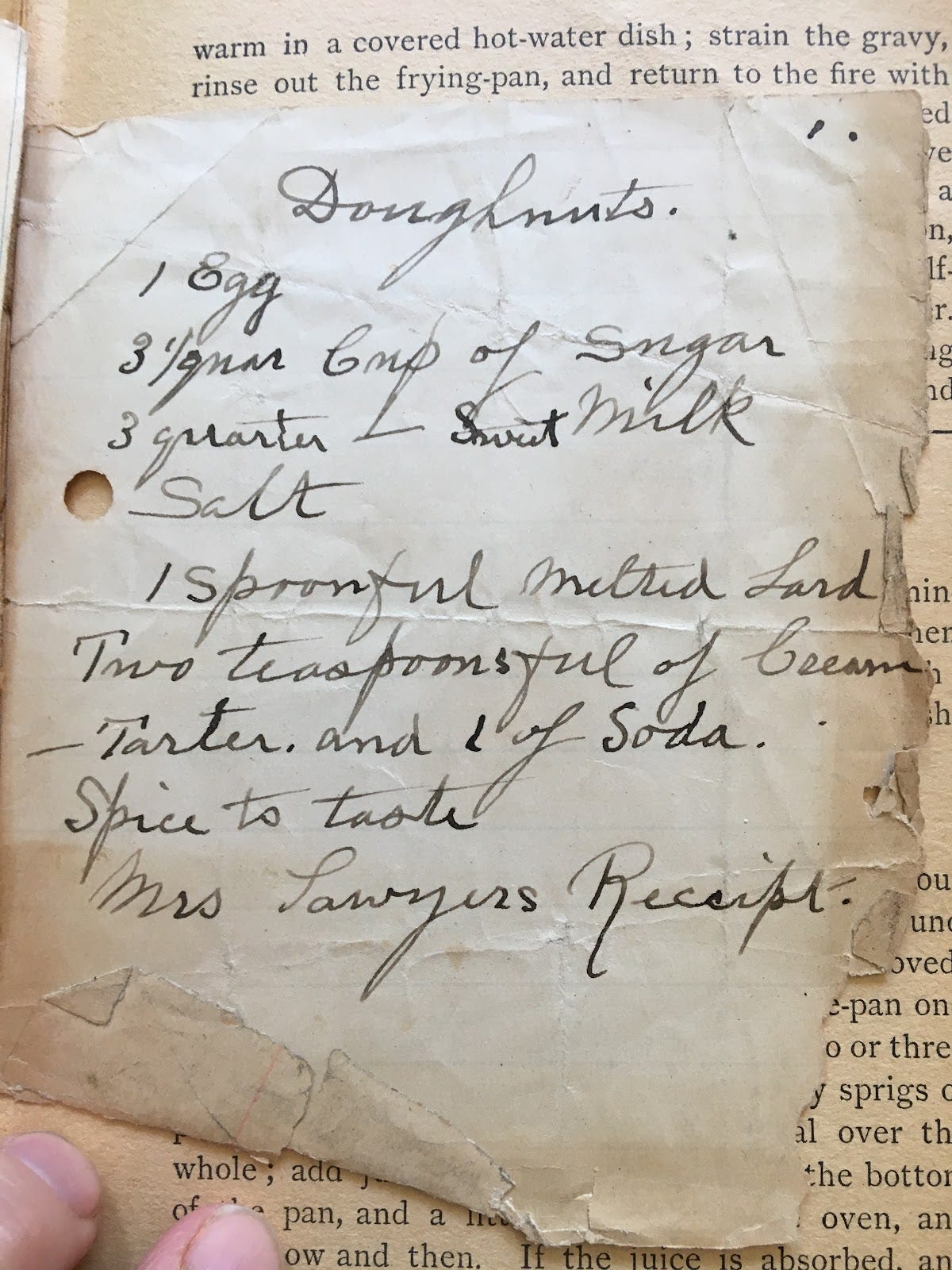

This fits with what I think about bread around the world, and over time. Reading old recipes – from the 1800s and even from the 1950s! – there are loads of instructions that do not specify how much flour to add. A bakers’ understanding of what a stiff dough, or a soft dough, was guidance enough. Reviving this familiarity is good for working with regional flours, because there’s so much variety available. Seasons and climate affect how grains grow; a bread wheat that grows in upstate New York will not perform like a bread wheat that grew in Kansas. The weather the crop was exposed to influences the way a grain grows. Those differences will be apparent in your bread dough, and make the flour thirstier, or not.

Feeling how different flours absorb liquid is instructive. Spelt will vary from a simple whole wheat loaf, or one made with a third rye. Each will feel different, and you’ll get some comfort with what you’re doing, notice when you need more water. Notice when you’ve mixed the ingredients enough.

The other song this method sings is the ever-changing nature of bread. Bread is different everywhere, varying by cultures, which each have their own ovens, and access to certain kinds of grains and flours. Over time, as William Rubel and Jeff Pavlik pointed out in their great Kneading Conference session, people have reimagined bread as necessary. And reinvention was always necessary! I wish we could tell everyone who thinks bread should be exactly one thing (AHEM, big holey crumb shots, no thanks!) that it is a million things, and in your hands, it will become yours.

Here is the handout we created. Please give it a try and let me know how it goes!

Yours, Amy

Lovely! Thanks for this, as it touched so many points for me: dear friends, letter-writing (which, alas, I rarely do anymore) and bread-making by feel. I've been looking back on people who were my bread teachers. When I was at university, my landlady, Penny, was a kind of saviour in so many ways, and one of her gifts was making bread without a recipe. I wrote about her in my bread blog a few months back. I still feel safest with a recipe/formula under my thumb, especially when scaling bread up for my baking business. Still, I always remember Penny when I drizzle a little extra water into the dough tub. Here's a link to my blog post for what it's worth: https://happymonkbaking.com/2021/04/24/a-bread-teacher-with-no-recipe/